News

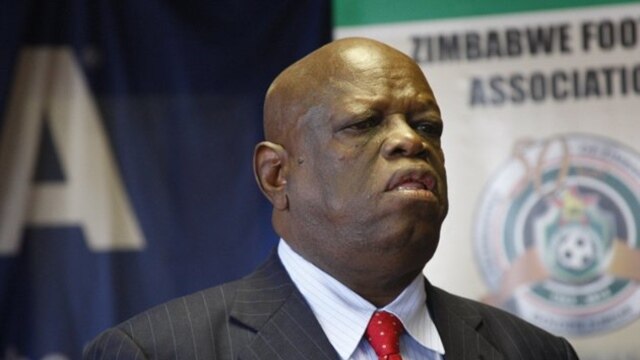

Tshinga Dube Dies

He trained as a guerrilla fighter in the Soviet Union and China in 1972, becoming a leading Zipra figure during the liberation struggle and one of the most prominent surviving ones until now.

Published

1 year agoon

By

NewsHawksZimbabwean former minister and liberation struggle stalwart, Tshinga Judge Dube, a wartime Russian-trained Zipra commander, who lived a colorful life and from time to time told his ruling Zanu PF leaders to shape up or ship out, died last night.

He was 83. Dube, who had endured serious health complications for a long time, died in the evening last night at Mater Dei Hospital in Bulawayo.

He lived in Killarney suburb in the country’s second largest city.

His son Vusa Dube said:

“I can confirm that my father Colonel (Retired) Tshinga Dube passed on today at 7:34pm Mater Dei Hospital in Bulawayo following a kidney failure. Of course, he has been unwell for the past 10 years, but his death came as shock to us a family.”

Vusa Dube , son to Tsinga Dube

Born on 3 July 1941 at Fort Usher in Matobo District, Matabeleland South, Dube became involved in politics at a young age, joining the liberation movement in the 1960s.

He trained as a guerrilla fighter in the Soviet Union and China in 1972, becoming a leading Zipra figure during the liberation struggle and one of the most prominent surviving ones until now.

Only last week at his home, even though bed-ridden, he had a great chat with a younger generation distinguished Zipra commander, retired Major-General Stanford Khumalo, who led a crack Zipra force during the legendary battles of the gorges against Rhodesian forces across Kariba, reminiscing about the past.

A 1970s Soviet-trained Zipra guerilla commander based in Zambia during the liberation struggle, Dube, who was a military communications and signals expert, played a key role during war of independence from Britain in the 1970s and 37 years later in the November 2017 coup which ousted the late president Robert Mugabe and installed his protege President Emmerson Mnangagwa as his successor. Zimbabwe got independence in 1980 under Mugabe, first as prime minister, later president.

Dube – known as Embassy during his struggle days – was in the thick of action from the 1960s throughout the 1970s and after independence until his death.

Following the 2017 coup, Dube did not play a significant government role in Mnangagwa’s administration.

He liked operating in the shadows and was probably one of the most underrated nationalists.

Prior to the coup, he had publicly urged Mugabe to resolve his explosive succession battle which was dividing the party and the nation, with potentially volatile consequences.

When Mugabe did not listen, Dube secretly worked closely with army commanders, mostly former Zipra, to stage the coup.

Never afraid to speak out his mind, he recently called out Mnangagwa on his unpopular plans to extend his rule to 2030 through back door.

In terms of the constitution, Mnangagwa is expected to complete his second term in 2028. Dube’s words will still ring louder on Mnangagwa’s ears as he navigates his 2030 plans in an explosive political minefield well after his death.

Dube recently told a local daily:

“There are various opinions on the succession issue. Most of the members of the party have said he should hang on to power, but he has said that he will follow the constitution. We have not heard him saying he wants to cling on to power beyond his term of office, but we should know that while men propose, God disposes. We do not know what is going to happen in four years to come, even spirit mediums do not know, only God knows. Advisers are problematic, those advising him are only looking at things that benefit themselves. We must be careful with the advice that we give to the President so that it does not benefit individuals only because we want his legacy to remain; these things can destroy his legacy after working so hard as a minister, surviving hangman’s noose and at the end of the day his legacy is destroyed like that.”

Tshinga Dube

Mnangagwa denies he wants to cling to power, but his allies and supporters insist he should stay on.

However, the President does not tell them to stop that; clearly indicating he is firmly behind the campaign.

Dube was one of the early Zipra cadres to train in Russia in the 1960s and 1970s. It was in January 1961 when George Silundika, a prominent nationalist leader of the National Democratic Party and later Zapu (future Minister of Roads, Road Traffic, Post and Telecoms in the first government of independent Zimbabwe) travelled to Moscow at the invitation of the Soviet Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee where he made a case of training guerillas for the liberation struggle forces.

From Silunndika’s liaisons, there were two groups under Zapu in 1964 that went to train in the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev, the same year Mnangagwa was sent to Egypt for training but ended up in China after a Zapu split in 1963, which led to the formation of Zanu.

One of the most illustrious Zipra commanders trained in Algeria, Alfred “Nikita” Mangena, got his nickname from the Russian leader. Some of the members of the two groups included Akim Ndlovu (the first Zipra commander), Dumiso Dabengwa, Ethan Dube, Robson Manyika, Ambrose Mutinhiri, Roger Matshimini Ncube and Phelekezela Report Mphoko.

Dube went after them.

They trained in various fields, including military combat and intelligence.

It was that training in intelligence that would, in later years, lead Dabengwa to be widely referred to as the “Black Russian” and “Intelligence Supremo”.

Dabengwa became the symbol of the effectiveness of Soviet training and cooperation between Moscow and African liberation movements, particularly in Southern Africa; Angola, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe, among others.

After their training the following year in 1965, they went back to Lusaka where a small High Command was created. Ndlovu was the commander with Dabengwa in charge of intelligence, Manyika chief-of-staff, Mphoko logistics, Roma Nyathi political commissar and Abraham Dumezweni Nkiwane in charge of personnel and training. Prior to that in 1962, there were already other trained personnel coming from Egypt and China, such as Misheck Velaphi Ncube, John Maluzo Ndlovu, Clark Mpofu, Luke Mhlanga and Joseph Zwangami Dube, and Amon Ndukwana Ncube, among others.

Dube later served with many more illustrious Zipra command element movers and shakers, the likes of Mangena, John Dube (Charles Sotsha Ngwenya), Eddie “Sigoge” Mlotshwa, Harold Mtandwa Chirenda, Jevan Maseko, Abel Mazinyane, Tapson Sibanda (Gordon Munyanyi), Cephas Cele, Ray Mutema, Albert Nxele and Philip Valerio Sibanda, among many others. A number of Zanla commanders, including the late famous Solomon Mujuru, came from Zipra, the military wing of Zapu, a key component of the liberation movement which included Zanu.

Zanla was Zanu’s armed wing.

Dube says in his memoir, Tshinga Dube: Quiet Flows The Zambezi, he used his close relationship with Mujuru to avert a full-scale civil war in Zimbabwe in the 1980s, which he thinks could have been worse than Mozambique and Angola, after Zipra cadres were dismissed from the Zimbabwe National Army at the height of political confrontation between Zapu and Zanu after 1980, which led to Gukurahundi.

Dube’s autobiography, edited by Fikile Nyathi and published by Amagugu Publishers, documents his early life, taking the reader through how he ended up participating in the armed struggle, the tumultuous splits in the liberation movement, betrayals and killings, combat period up to the time of the ceasefire ans Lancaster House Conference in 1979.

It also covers the promising, hopeful and yet tense and perilous early years of independence which saw military brinkmanship between Zipra and Zanla, including open clashes in Entumbane in 1981 and 1982.

The book reveals untold stories about tensions characterising the Zimbabwe National Army in its formative years amid rivalries and suspicions between the Zipra, Zanla and Rhodesian Army forces during integration.

Dube was in the integration committee which included Zanla and Rhodesian commanders. The memoir includes many other interesting events, including Gukurahundi, the Simon Mann Equatorial Guinea coup plot in 2004 and the November 2017 coup in Zimbabwe, among others.

In 1966, the same year as Zanla’s Chinhoyi Battle, after his return from training in the Soviet Union, Dube and a small group infiltrated south western parts of Zimbabwe, in what later became part of the preparation of the first two major guerilla military incursions into Rhodesia, the Wankie Campaign (1967) – the Luthuli Detachment involving Zipra and South Africa’s liberation movement ANC and its military wing Umkhonto weSizwe – and Sipolilo Battle (1968).

The Wankie Battle, the biggest battle fought in Rhodesia at that time, was commanded by John Dube (Sotsha Ngwenya), deputised by Chris Hani from MK. Other MK commanders included Joe Modise and Zola Zembe.

A number of skirmishes between the two opposing forces lasted from 13 August to 4 September 1967.

Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith had to invite his South African counterpart John Vorster to send South African security reinforcements to Rhodesia to counter the guerilla forces.

The Rhodesians called their military campaign against the ANC-Zapu alliance Operation Nickel. During the course of the ensuing battles both sides claimed victories.

Soon after the Wankie Battle, there was the Sipolilo Campaign in 1968 commanded by Moffat Hadebe, who says he is the first guerilla to fire shots of the liberation struggle at Zidube Ranch in Kezi in 1964 to signal the beginning of military confrontation, two years after the first group of guerillas were trained in Egypt.

Hadebe is one of the most prominent pioneering commanders of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle and his nom de guerre was Morris Dlomo.

Dube witnessed the formation of Zipra in the early to mid-1960s until its absorption into the new national army after integration in which he played a critical role.

Dube’s career and life was dramatic.

Apart from the liberation struggle, he was a player in political and military events in the early of years of independence and subsequently in national affairs, and was involved in arms dealing and diamonds trade in the process.

After independence in 1980, Dube was involved in integration of three warring armies, Zipra, Zanla and the Rhodesian forces, served in the new national army that he helped form, government departments and parastatals; that is the Zimbabwe National Army, Ministry of Defence, Zimbabwe Defence Industries (ZDI), Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation, Marange Resources, TelOne, War Veterans association, advisory board member to the secretary-general of the United Nations on Disarmament, deputy minister and later minister, among other roles.

During the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) war, in which Zimbabwe was involved from 1998 to 2002, for instance, Dube sold arms and dealt in diamonds, making a fortune for himself.

As a result, he was named in the UN Security Council Report, Plundering of DR Congo natural resources: Final report of the Panel of Experts (S/2002/1146), which in paragraph 29, states that it had learnt of a secret new Zimbabwe Defence Force diamond mining operation in Kalobo in Kasai Occidental run by Dube Associates. Dube apparently worked with Zimbabwean army commanders during “Operation Sovereign Legitimacy”, the the code-name under which Mugabe got involved in the DRC war, a conflict that partly led to Zimbabwe’s current economic implosion and political instability.

The Zimbabwean army operated in the DRC diamond mining fields through its company Cosleg and other shadowy structures.

Describing the presence of military-corporate networks in DRC and the looting of minerals, the 2002 UN report said: “Although troops of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces have been a major guarantor of the security of the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo against regional rivals, its senior officers have enriched themselves from the country’s mineral assets under the pretext of arrangements set up to repay Zimbabwe for military services.

Now ZDF is establishing new companies and contractual arrangements to defend its economic interests in the longer term should there be a complete withdrawal of ZDF troops.

New trade and service agreements were signed between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zimbabwe just prior to the announced withdrawal of ZDF troops from the diamond centre of Mbuji Mayi late in August 2002.

“Towards the end of its mandate, the panel received a copy of a memorandum dated August 2002 from the Defence Minister, Sidney Sekeramayi, to President Robert Mugabe, proposing that a joint Zimbabwe-Democratic Republic of the Congo company be set up in Mauritius to disguise the continuing economic interests of ZDF in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The memorandum states: ‘Your Excellency would be aware of the wave of negative publicity and criticism that the DRC-Zimbabwe joint ventures have attracted, which tends to inform the current United Nations Panel investigations into our commercial activities.

It also refers to plans to set up a private Zimbabwean military company to guard Zimbabwe’s economic investments in the Democratic Republic of the Congo after the planned withdrawal of ZDF troops.

It states that this company was formed to operate alongside a new military company owned by the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

” The UN report refers to Dube and other key Zimbabwean politico-military figures involved in mining during the DRC war. “

The key strategist for the Zimbabwean branch of the elite network is the Speaker of the Parliament and former National Security Minister, Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa.

Mr. Mnangagwa has won strong support from senior military and intelligence officers for an aggressive policy in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

His key ally is a Commander of ZDF and Executive Chairman of COSLEG, General Vitalis Musungwa Gava Zvinavashe.

The General and his family have been involved in diamond trading and supply contracts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A long-time ally of President Mugabe, Air Marshal Perence Shiri, has been involved in military procurement and organising air support for the pro-Kinshasa armed groups fighting in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

He is also part of the inner circle of ZDF diamond traders who have turned Harare into a significant illicit diamond-trading centre.

Other prominent Zimbabwean members of the network include Brigadier General Sibusiso Busi Moyo, who is Director General of COSLEG. Brigadier Moyo advised both Tremalt and Oryx Natural Resources, which represented covert Zimbabwean military financial interests in negotiations with State mining companies of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Air Commodore Mike Tichafa Karakadzai is Deputy Secretary of COSLEG, directing policy and procurement. He played a key role in arranging the Tremalt cobalt and copper deal.

Colonel Simpson Sikhulile Nyathi is Director of defence policy for COSLEG. The Minister of Defence and former Security Minister, Sidney Sekeramayi, coordinates with the military leadership and is a shareholder in COSLEG.

The Panel has a copy of a letter from Mr. Sekeramayi thanking the Chief Executive of Oryx Natural Resources, Thamer Bin Said Ahmed Al Shanfari, for his material and moral support during the parliamentary elections of 2000.

Such contributions violate Zimbabwean law. In June 2002, the panel learned of a secret new ZDF diamond mining operation in Kalobo in Kasai Occidental run by Dube Associates.

The UN report added:

“This company is linked, according to banking documents, through Colonel Tshinga Dube of Zimbabwe Defence Industries, to the Ukrainian diamond and arms dealer Leonid Minim, who currently faces smuggling charges in Italy. The diamond mining operations have been conducted in great secrecy…”

Prior to that, in the mid-1990s, ZDI, under Dube, was contracted by the Sri Lankan government to manufacture and supply them with arms. But the Sri Lankan rebel group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, captured one of the shipments, sparking a crisis.

This resulted in investigations by the Sri Lankan government and journalists, exposing an arms scandal in which Dube was implicated.

Dube was later entangled in another controversy involving arms dealing, money and a coup Equatorial Guinea.

He was a major player in the 2004 coup plot drama by former British Special Services soldier Simon Mann and his band of mercenaries in a bid to oust oil-rich Equatorial Guinea President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo.

In his 2011 book, Cry Havoc, Mann confirms he dealt with Dube and the intention of the Malabo-bound mercenaries was “to remove one of the most brutal dictators in Africa in a privately organised coup d’etat.”

A NewsHawks editor, then working for the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper as a news editor, was closely involved in reporting the story at the time.

The journalist interviewed Dube on the issue and in one such an engagement, he explained his role in detail, while eventually pleading with the reporter: “Lalela mfanami, musa ukungidonsela isinkwa emlonyeni.

Wena bhala ezinye izindaba uphume kuleyi. (Listen my boy stop grabbing bread from my mouth, write other stories and leave this one alone); which in Ndebele meant stop depriving me of my opportunity to eat, or have something essential; write other stories and leave this one alone.

Dube was pleading with the journalist to avoid exposing his role in arms dealing with Mann and inadvertently supporting the coup plot, from which he double-dipped.

With those words, Dube gave his side of the story and told the reporter to go and write that.

Typically calm, secretive and cunning, Dube had sold arms to Mann and his mercenaries to make money, but then later laid a trap for them to be arrested at Manyame Airbase in Harare on 7 March 2004 when the whole plot unravelled as it was exposed through intelligence cooperation between South African and Zimbabwean security services.

The story of Mann, his band of mercenaries and the coup plot against Nguema is documented more in detail and vividly by British journalist James Brabazon, an award-winning documentary filmmaker, who got help from the local journalist in question by way of giving him crucial documents to corroborate his investigation.

The journalist’s contribution is acknowledged in the book. As detailed in Brabazon’s book, My Friend The Mercenary: James Brabazon, A Memoir, the story – a classic case of intrigue, greed and violence, spans a chain of events across at least five African countries – South Africa, Zimbabwe, Liberia, Guinea and Equatorial Guinea. DRC is also mentioned too.

The media, including Zimbabwean journalists, at the time simply could not connect the dots, but it later emerged it was one of the biggest Africa continental stories which could ever be told in contemporary journalism.

The story was supposed to involve the first coup in history to be filmed realtime and live, James Bond-style, by Brabazon.

The summary of the book: In February 2002, Brabazon set out to travel with guerrilla forces into Liberia to show the world what was happening in that war-torn country then.

To protect him, he hired Nick du Toit, a former South African Defence Force special services soldier who had fought in conflicts across Africa for over three decades, including in Rhodesia.

What follows is an incredible behind-the-scenes account of the Liberian rebels — known as the LURD — as they attempted to seize control of the country from government troops led by former president Charles Taylor.

In this gripping narrative, Brabazon paints a brilliant portrait of the chaos that tore West Africa apart: nations run by warlords and kleptocrats, rebels fighting to displace them, ordinary people caught in the crossfire amid untold suffering — and everywhere adventurers and mercenaries operating in war’s dark shadows looking for diamonds.

It is a riveting account, which links with the coup as Du Toit was an actor across the plots and events; a tale about what it takes to be a brave journalist, survivor, and true friend in this morally corrosive crucible.

In the process, Du Toit promised Brabazon the scoop of his life: a front seat, beside Mann, in an audacious coup attempt in Equatorial Guinea.

By some twist of fate, Brabazon had a family emergency and missed a flight to join the coup-plotters. That saved his skin.

His book could have been about his trials and tribulations in jail, that is if he would have survived torture and Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison dingy conditions and those at the equally notorious Black Beach on Bioko Island, Malabo.

The book is in two parts: the first section tells the story of Brabazon’s documentaries shot during the civil war in Liberia.

He hired Du Toit, an ex-professional soldier and mercenary, to protect him in the warzone and they formed a very strong bond of friendship during their extreme experiences in the combat zones.

Du Toit in the process told Brabazon about some of the mercenary activities he was previously involved in and upcoming incredible plans, which involved staging a coup in a west coast Central African country and former Spanish colony, Equatorial Guinea.

To cap it all, Du Toit then suggested that the journalist should film it.

Sensing an opportunity to propel himself to fame through a ground-breaking story, unparalleled in modern journalism, Brabazon agreed, but due to his grandfather’s funeral, he was not there when the coup plot was foiled so he was extremely lucky not to have been arrested, tortured and kept in a hellhole of a jail for over five years, as his friend Du Toit was.

The second half of the book, which changed Brabazon’s career and life, is about the author’s search to uncover the truth of the plot that his friend got involved with and why it all went so horribly wrong in Zimbabwe and ends with his reunion with him after he was pardoned and released five years and nine months into a 34-year jail sentence.

This is an unusual account of an unlikely friendship and the journalist spends a fair amount of time considering the ethically murky situations that he finds himself in.

Back in Harare, after flying out of South Africa on 7 March 2004, Mann’s American-registered plane (still grounded in the Zimbabwean capital) was impounded as it landed at the Harare International Airport (now Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport) and taxed to Mnyame Airbase with 70 mercenaries enroute to Malabo, Equatorial Guinea.

After some anxious moments, days and months of high drama, Mann and his group was tried and jailed seven years before being transferred to Malabo in 2008 to face yet another trial and prison term.

Mann was initially convicted in Zimbabwe of attempting to buy arms illegally from Dube for the coup plot and sentenced to seven years imprisonment at Chikurubi where he says he became a close jail friend with dodgy Zimbabwean tycoon Wicknell Chivayo.

In Equatorial Guinea, Mann was sentenced to 34 years in prison for plotting to overthrow Nguema.

The Eton-educated former British Special Air Services officer was jailed after a nail-biting trial during which it was revealed a number of western governments knew about the coup plans.

The court heard that Sir Mark Thatcher, the son of the late former British prime minister, was involved.

Mann was later pardoned and made security adviser to Nguema, then paid handsomely in a unlikely turn of events. Apart from the Equatorial Guinea coup, Dube was 13 years later a critical player in the shadows during the 2017 coup led by Mnangagwa, Vice President Constantino Chiwenga and others.

Former Zipra and Zanla commanders, who were at each other’s throats during and after the war, collaborated to oust Mugabe. After 2017, Dube, whom some ex-Zipra commanders wanted Mnangagwa to appoint Vice President at the expense of Kembo Mohadi, an ex-Zipra military intelligence cadre, retreated to the shadows, his favourite operational grounds.

In the shadows, he disappeared from the spotlight due to ill-health, only making occasional appearances in public.

Away from politics and statecraft, Dube was a businessman, a wheeler-dealer if you may, and philanthropist.

He donated to social causes and charity. He also financially supported his favourite football club, Highlanders, which was one of the biggest things close to his heart.

Highlanders will never get any such a benefactor and consistent life member. Dube at one time brought in to Zimbabwe the late American king of pop Michael Jackson to Zimbabwe.

He also brought in South African musicians. Always colourful in his life and politics, Dube’s parting short to Mnangagwa in his public remarks is significant : Don’t listen to those opportunists surrounding you as they want you to cling to power to 2030 for their own self-serving ends, not in your own interest.

Will Mnangagwa listen to Dube’s advice beyond his grave or not? Only time will tell.

– The NewsHawks Editorial.

You may like