Opinion

The state of democracy in the Sadc region: A reflection on the national elections of Zimbabwe

Published

10 months agoon

By

NewsHawksIBBO MANDAZA

I: The context: OR Tambo’s legacy

THREE weeks ago today, this lecture was unceremoniously cancelled by the Secretary-General of the African National Congress (ANC), Fikile Mbalula. In an email letter on the 6th of September, a day before the scheduled lecture, Mbalula directed the head of the OR Tambo School, David Masando, “that the lecture should not proceed on Thursday 7th September, 2023.” The correspondence was copied to Cdc K. Motlanthe, Chairperson of the Board of the OR Tambo School of Leadership.

Significantly, Mbalula was writing out of Harare where he had accompanied President Cyril Ramaphosa for Mnangagwa’s inauguration on 4 September. And so while Ramaphosa returned to South Africa soon after the inauguration ceremony, Mbalula and his entourage extended their stay for discussions with their Zanu PF counterparts.

Speculation is rife as to the nature of the meetings between the ANC and the Zanu PF, with references to “cheque book diplomacy” (about which we will soon know more), but Mbalula’s email letter suggested that the discussions included the subject of the messy election in Zimbabwe on 23 August, 2023. And so I quote the sentence that was suggestive of the ANC being engaged with the crisis in Zimbabwe:

“At this moment the leadership of the ANC is engaged in a number of delicate engagements regarding the situation in Zimbabwe. In this context, a public lecture, at this time, on what is clearly an ANC platform, would complicate these initiatives.. We invite you to engage with us further on the detail of these matters, and the possibility of the lecture being held in future, in a different format, and on a different platform.”

I am not sure, though I remain as suspicious, at the reference to a ”different format” and ”on a different platform.” Whatever the import of these words, it is clear that David Masondo and his comrades stuck to their guns, postponing the lecture as they have done, with the same title, format and platform. I am therefore pleased to be here as part of the assertion of academic freedom and a large response to those in our midst who dare try to muzzle the few corridors of intellectual and ideological discourse in post-liberation Southern Africa. In this regard, let me quote from one of the many comrades, at home and across the diaspora, who were outraged at Mbalula’s email letter which, thanks to social media, had gone viral within hours of its dispatch from Harare. Apologies, David, if I’m inadvertently betraying confidences, but a mutual comrade confided in me and I’m likewise confiding in my audience, appropriately:

“Good evening Cde David, I hope this message doesn’t offend you. At any rate, I would strongly encourage you to stand fast against any interference with the OR Tambo School’s total autonomy and power to decide who to invite to speak on any subject your institution deems appropriate. Any abdication of this principle would be a betrayal of the principles OR lived for and upheld. it is your board’s responsibility to uphold this cardinal principle.”– Mavuso Msimang.

I want to add here, how critical, and indeed most legitimate, that more and more of those of us who are from the ranks of the former liberation movements stand up and be counted, to inspire the younger generation, keep the flame of liberation alive, and remain a thorn in the flesh of those amongst us who have since gone rogue and constitute an embarrassment to the history and objectives of the liberation struggle. Yes, who will dare shut us up comrades? Who amongst them has that moral authority? Need I say more?

And now to the topic of my lecture, after that very useful digression and an open challenge to those in our midst who have since gone rogue.

The state of democracy in the Sadc region I will spend less on the elections per se and more about Sadc whose Election Observer Mission (SEOM) has at last plucked the courage to state the reality that has been the nature and content of the crisis In Zimbabwe over the last two decades. More significant in this regard is the extent to which all this has exposed the cowardice of many of the current leadership in Sadc, while providing this opportunity to remind all of us of the origins and mandate of the regional body itself. In doing so, to prompt Sadc to take on its responsibility in the face of the crisis in Zimbabwe, convene the Extraordinary Summit as it has done several times before over the four decades of its existence. For, we have to remember that Sadc was born out of the liberation struggle in Southern Africa, the successor of the FrontLine States that were the backbone and rear guard of the struggles in Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa, and today, the custodian of peace, security and stability in the sub-region.

II: THE 23 August election in Zimbabwe: the unending legacy of disputed elections

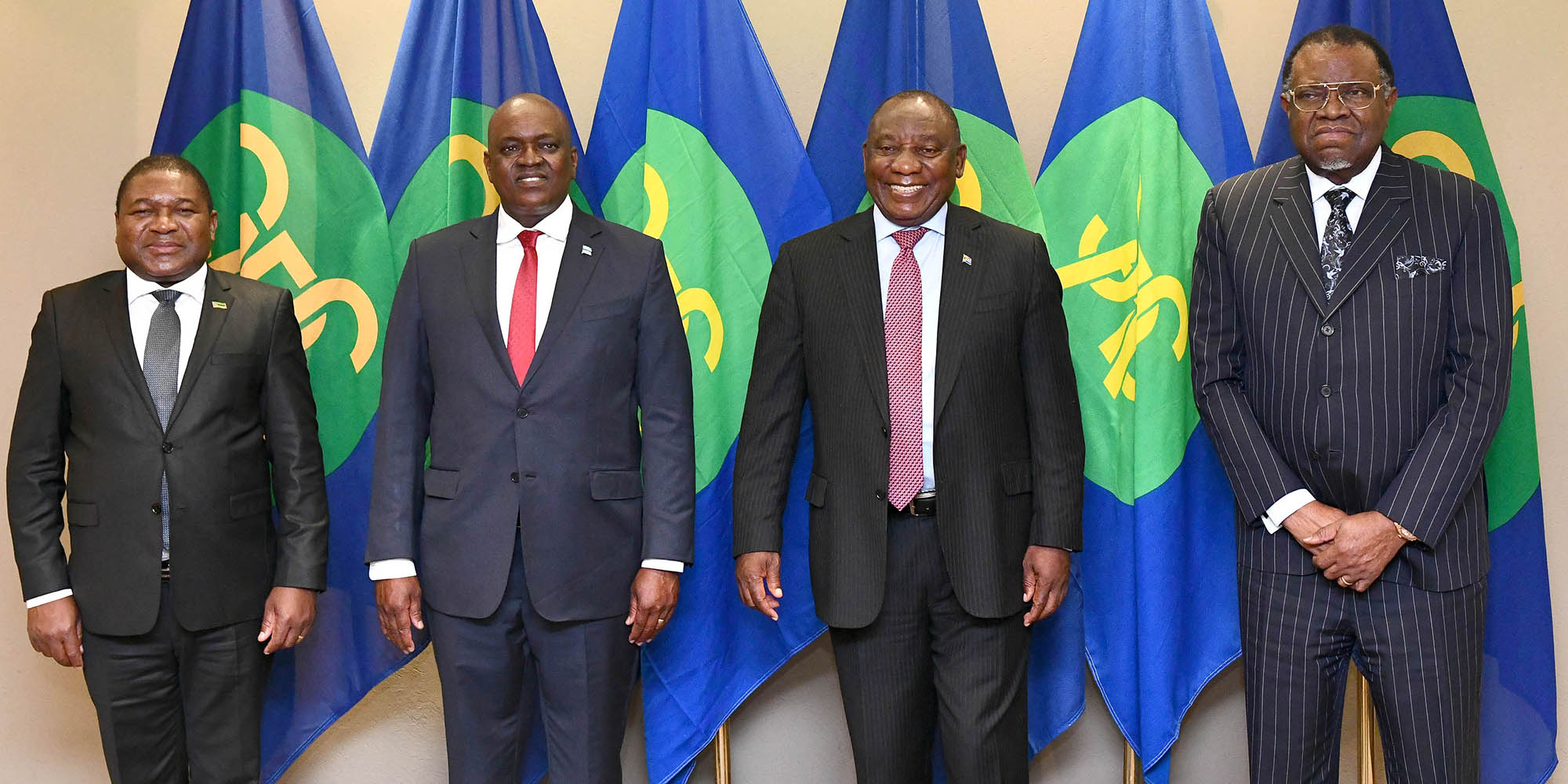

Understandably, the Sadc Election Observer Mission Report (SEOM) on the 23rd of August harmonised election in Zimbabwe has taken centre stage and refuses to go away. But it was not the only Observer Mission Report that returned a negative verdict on the poll. There are the European Union Observer Mission (EUOM), Carter Centre, Commonwealth Observer Group (COG) and African Union (AU-Comesa) reports. Although there has been little or no reference to them, the ANC, Swapo, Frelimo, CCM (Tanzania), MPLA, Malawi Congress Party (MCP) and the Botswana Government, also dispatched observer missions to Zimbabwe. There is no guessing why these observer mission reports have not been made public; but none have yet contradicted the import of the SEOM which has clearly left the authorities in Harare embarrassed and wounded, while most of the Sadc member states, and indeed the AU generally, appear to have acknowledged its findings by neither congratulating Mnangagwa nor attending his inauguration. President Ramaphosa In particular has made some clumsy statements on the subject, at the risk, states an observer on social media, of “breaking the rules of procedure and undermining the authority of Sadc by taking a position on the Zimbabwean issue before the region decides (at the Extraordinary Summit that appears inevitable).”

In this regard, sections of the media have caricatured Ramaphosa’s position on Zimbabwe.

For example, Business Day of the 21 September 2023 had this very suggestive cartoon on “Premature Congratulations” : with Ramaphosa stating that “The Zec made a declaration and on that basis we issued our congratulations to President Mnangagwa;” and on the side of it: “This Just In: EU to withdraw US$5 million financial aid to the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec) due to election irregularities and lack of transparency.”

Nonetheless, Ramaphosa’s stance on the recent elections in Zimbabwe is welcome relief to the authorities in Harare, not least his comments that no election is perfect nor without challenges (“ even in the USA…”). But, surely, how does one ignore the stark reality that Zimbabwe has been the sick man in a region–particularly in South Africa itself–in which free, fair and credible elections are the order of the day, where ruling and opposition parties can interact, either in business or jest, as fellow citizens of one country? By contrast, the Zanu PF state in Zimbabwe has since Independence treated opposition parties as enemies to be vanquished: whether it was Joshua Nkomo and Zapu, Edgar Tekere and Zum, Morgan Tsvangirai and MDC, and now Nelson Chamisa and CCC. It has jailed without trial (political) prisoners like Job Sikhala and Jacob Ngarivhume, manipulates the delimitation report and the voters roll, and has virtually captured to itself the judiciary and the law enforcement and security apparatus.

As Blade Nzimande observed in his remarks on a Zanu PF that had by 2000 since lost the very forces that constituted it during the struggle:

“Now you know, comrades, when we went to Zimbabwe….. as part of the South Africa Communist Party fact finding mission…… When we engaged with our Zanu Pf comrades everybody was the enemy: ZCTU was the enemy, professionals, academics, everybody! But we asked, how come comrades all these forces you are saying are enemies, were they not part of the victorious forces led by Zanu PF on the victory of your struggle in 1980? What has changed? Zanu PF has lost the middle classes, has lost the professionals and has lost many urban-based organisations; it has become a rural party because of the mistakes they were making. Now the comrades are denying that there is a problem . There is a danger once liberation movements begin to lose power or sense that they are losing power — they start doing a lot of funny things. The first thing they start doing is coming up with ‘radical’ concepts. Mugabe lost a referendum and started a ‘radical’ land reform. They took land anyhow… and if they do not succeed, they unleash the security forces on the population.”

Indeed, both the electoral process over the last year and the poll itself on 23 August 2023, were part of a major security operation the likes of which has not been seen before in Zimbabwe. Not to mention again the point that every election since 2000 has been rigged and/or ended in dispute. As Nigerian activist Aisha Yesufu stated recently; “Until rigged elections are treated in the same as coups, democracy will continue to be in danger.”

Clearly, the 23 August 2023 election is in serious dispute and joins the series of “coups” (not excluding the military one of November 2017) . The very antithesis of democracy itself, and renders the electoral process farcical, just a mechanism through which the securocrat state seeks to renew its illegitimate mandate, especially and significantly with respect to the presidential poll. As we have pointed out before, by all accounts, Robert Mugabe lost to Morgan Tsvangirai in the presidential polls of 2002, 2008 and 2013. Closer scrutiny of the 2018 elections would appear to confirm the view of a member of analysts that Emmerson Mnagagwa likewise, lost to Nelson Chamisa. The security operation – including the deployment of the shadowy Faz and the calculated delay in the supply of ballot papers in Harare and Bulawayo on polling day, with many polling stations securing these well into the night of 23rd August and even on the following day 24th of August – that accompanied both the electoral process and polling day itself, should leave no one in any doubt as to the extensive rigging that underpinned Mnagagwa’s wafer-thin “victory” of 52% (to Chamisa’s 44%). Time will soon confirm, but we can confidently conclude that the election as a whole was neither, free, fair nor credible. A most depressing, if not cynical, feature about elections in Zimbabwe is the extent to which elections are so brazenly stolen and the voters rendered useless statistics. Deplorable! Depressing. More so when we hear would-be statesmen glibly dismissing a pattern that has become legion in Zimbabwe as mere “challenges” that can be addressed in the future. Not to mention the shamelessness with which one can stand before the UN and claim that such an election was free, fair and credible!

III: What is to be done? The necessity and urgency of Sadc intervention in the Zimbabwe crisis

There was initially the obvious expectation that the Sadc Troika of Politics, Defence and Security Co-operation would be seized immediately with the Zimbabwe situation, especially given the verdict of the Sadc Election Observer Mission (SEOM) Report on 30 August 2023 (with the final version submitted on 4 September, just before Mnangagwa was inaugurated). Since then, there has been a discernible vaccilation and even debate as to the mandate of Sadc and its Organ. All this quite apart from the emotional outpourings out of government spokespersons — and other critics of Mumba, the head of SEOM — in Harare: crude attacks on the person of Mumba and even against President Hichilema. Most unprecedented and certainly bordering on serious diplomatic breach on the part of the Government of Zimbabwe towards its northern neighbour.

Notwithstanding a statement from Ramaphosa on the very day he was defending his congratulatory message to Mnangagwa, that Sadc would have to meet and discuss the report, the retort out of Harare in particular and the region generally has been to throw doubt on the mandate of Sadc in these matters, let alone its capacity to do anything. Including the following statement, purportedly from the Sadc secretariat itself, but dubious given our understanding of the mandate of Sadc: “SADC ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSIONS

ONLY observe elections. Sadc does not conduct elections in its member states but observes them. We then make recommendations. Understand the role of Sadc. When it comes to observing elections. Our mandate is only to observe and issue a report.”

All this might reflect on the lack of political will on the part of the current leadership of Sadc, but it is certainly the very antithesis of the mandate of the regional body’s Windhoek Treaty of 1992, its Organ on Politics, Defence and Security of 1996, and the Sadc Electoral Advisory Council (SEAC) which was formed by the Organ in 2005. To quote the latter.

The Southern African Development Community (Sadc) Electoral Advisory Council (SEAC) was formed to transform election observation, the conduct of democratic elections and the prevention of electoral related conflicts in the Sadc region.

Established in August 2005 in terms of Article 9(2) of the Sadc Treaty by the Sadc Summit held in Gaborone, Botswana, SEAC’s broad mandate is to advise Sadc on matters pertaining to elections, democracy and good governance.

The overall objective of SEAC is to contribute to the prevention of electoral related conflict in the Sadc region through the design and implementation of a conflict prevention strategy focused on each stage of the electoral cycle that outlines the specific contribution of SEAC.

The proposal to establish SEAC resulted from a stakeholder workshop convened by the Sadc secretariat in Lesotho in 2004. Stakeholders recommended that Sadc form a mechanism that would not only guarantee the implementation of the Sadc Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections but also strengthen the capacities of Electoral Management Bodies (EMBS) and facilitate the work of the SADC Electoral Observation Missions (SEOMs).

Following a comprehensive assessment of the workshop recommendations, the Ministerial Committee of the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security (MCO) recommended to the Heads of State Summit, the formation of SEAC. After SEAC’s formation in 2005, the MCO adopted the SEAC Structures, Rules and Procedures in March 2009. SEAC was officially established in August 2010 at Maputo, Mozambique and inaugurated on 13 April 2011 in Gaborone, Botswana.

According to the SEAC Structures, Rules and Procedures, the main objective of SEAC shall be to advise Sadc, through the MCO, on issues pertaining to elections and the enhancement of democracy and good governance. In addition to its main objective, the specific objectives of SEAC are:

● To urge and encourage Sadc Member States to adhere to Sadc Principles and Guideline Governing Democratic Elections;

● To encourage Sadc Member States to adhere to international best practices whenever they are holding elections;

● To advise Sadc Member States on strategies and issues to enhance and consolidate capacity of EMBS in the Sadc Region; and

● To encourage Sadc Member States to uphold and respect the independence and autonomy of Electoral Management Bodies.

Of course, SEAC is derived from the provisions of the Sadc Treaty of 1992, and its overall objective of creating an integrated community of nations as part of the building blocs towards an integrated African Union. Implicit in all this is that member states necessarily forego part of their sovereignty in the interest of the larger whole. But those of us who were charged in 1996 with the responsibility to draft the protocols of the Sadc Organ on Politics, Defence and Security, were informed by these ideals of regional and continental unity, and the quest for a Common Foreign Policy, through which to prevent conflict, promote peace and stability and, if necessary, attend to, and deal with, an errant member state. We were aware, of what I referred to in 1998, on the occasion of the Sadc intervention in Lesotho, as the “hierarchy of powers” implicit in all regional and global organisations,

This is the extent to which some member states therein wield more power than others, tend to be politically and economically hegemonic in a given region, or lend themselves into the so- called permanent members of the UN Security Council (USA, China, Russia, Britain and France).

In short, there has always been the inplicit acknowledgment that South Africa is the hegemon in Sadc. Of course, Zimbabwe, particularly under Mugabe as the latter tried to challenge Mandela as the obvious giant that he was, has always tried to play the card of precedence or seniority, as the case may be. It was this untidy relationship between Mandela and Mugabe, especially over the crisis in DRC in 1998, that led to the Defence Pact, signed on 31 July that year, sponsored by Zimbabwe and including the three other members, namely Angola (who were equally perturbed at Mandela’s hosting of Savimbi in Pretoria), Namibia and the DRC itself. Suffice it to state that this Defence Pact, although designed within the ambit of the Sadc Organ on Politics, Defence and Security of 1996, nevertheless constituted a serious threat to Sadc itself, at least to the extent to which it was meant to warn Mandela’s South Africa, which was a loudly opposed to the intervention in DRC and whose overtures to Savimbi and Mobutu were regarded as offensive on the part of Angola and DRC respectively.

In retrospect, both these developments and the precedents in which Sadc had an interventionalist role, would have helped to grow the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security, and informed and underpinned SEAC itself. The more reason why Sadc itself, the member states therein, and the current heads of state of the regional body, should be reminded of their respective responsibilities in the face of the disputed elections in Zimbabwe.

Indeed, we need to list the precedence in terms of Sadc’s intervention in the face of similar cases over the years, if only to highlight the capacity and responsibility of the regional body in the face of such crises:

The Final Phase in the Liberation of Namibia and South Africa: working as both Front Line and Sadc states, the latter were invaluable in both the isolation of apartheid South Africa and the enforcement of global sanctions against Pretoria, whilst providing support to the liberation movements – including the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) and the United Democratic Front (UDF) — in Namibia and South Africa.

The Rome Accords for Peace in Mozambique (1990) : under the auspices of Sadc, and as the leader of the country which had provided military support to Mozambique in its fight against Renamo, Robert Mugabe was a key factor in the Rome Accords which brought peace to the former Portuguese colony.

The Lesotho crisis: September 1998 to May 1999: Sadc intervention through South Africa having to deploy military force to quell a crisis following a disputed election in that country.

The DRC War: 1998 to 1999: with Angola, Zimbabwe and Namibia actively involved in supporting Kabila, the other Sadc countries like Tanzania, Zambia and Mozambique provided support in various ways at their disposal.

Sadc intervention in the DRC: to state the least, Sadc, through its Organ on Politics, Defence and Security, has been engaged with the situation in the DRC since 2014 to the present. On 8th May 2023, a Summit of the 16-bloc Sadc agreed to deploy Sadc troops to the DRC, to help quail violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where groups have terrorised civilians for decades. In fact, there has developed a possible combination of such Sadc forces and those of the East African Community troops from the three Sadc countries — Malawi, South Africa and Tanzania — have operated in eastern DRC for a decade under the United Nations peacekeeping force Monusco. Following a meeting of the Sadc Troika on Politics, Defense and Security on 8th May, 2023, and again on 11th July 2023, Sadc approved “the mandate, legal and operational instruments necessary for the deployment of the Sadc mission in DRC, that is SAMIDRC. To quote the communiquè:

“This exchange between the sub-regional heads of state, opened by Namibia’s Hage Geingob and chaired by Zambia’s Hakainde Hichilema, followed several other meetings of the various Sadc bodies. On 4 July 2023, the organization’s defense sub-committee met in Windhoek, Namibia, to discuss the technical details of this deployment, with the issue being raised again on 10th July at the meeting of Sadc Troika on Politics, Defence and Security.”

Just yesterday, the Troika met virtually under the Chairmanship of President Hichilema of Zambia, together with Presidents Samia Suluhu Hassan of Tanzania and Hage Geingob of Namibia, on the deployment of Sadc forces to eastern DRC on 30 September, 2023. This is a 12-month mandate up to 30 November 2024, with possibly a South African Defence Force command and a budget of US$554 552 472.

“This sum, which is subject to change and intended to cover the first 12 months of the operation, is based on the estimated needs of a workforce of around 5 000 people. In theory. It should cover the cost of the Sadc secretariat, the office of the head of mission, and, above all, the military components of the force as well as the equipment (African Report, 21 July, 2023).”

All indications are that the Zimbabwe election issue, including the SEOM report, would have been on the agenda of the Troika meeting yesterday, but certainly to be dealt with in the not too distant future.

Sadc intervention in Madagascar: After suspending Madagascar from Sadc in November 2009, the Extraordinary Summit of Sadc held in Sandton, South Africa, in June 2011, prescribed a roadmap on the basis of which the member state was re-admitted to the regional body in 2014.

IV: Sadc and Zimbabwe

Turning to Zimbabwe specifically. Sadc has had two Extraordinary summits on the country in less than two decades:

● 28-29 March, 2007, — Dar es Salaam, following the brutal and physical attacks by state-related agents on Morgan Tsvangirai and his lieutenants on 7th March 2007. So incensed was the region and the world at such barbaric behaviour that the Extraordinary Summit mandated President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa to continue to facilitate dialogue between the opposition MDC and Mugabe’s Government, and report to the Troika.

● 1 July 2008 – Sharma El-Shaikh, Egypt. SADC/ African Union Summit Resolution on Zimbabwe,following the disputed and Violent run-off election of June 2008. The Summit decided as follows:

1. To encourage President Robert Mugabe and the leader of the MDC Party Mr Morgan Tsvangirai to honour their commitment to initiate dialogue with a view to promoting peace, stability, democracy and the reconciliation of the Zimbabwean people.

2. To support the call, for the creation of a Government of National Unity.

3. To support the Sadc Facilitation, and to recommend that Sadc mediation efforts should be continued in order to resolve the problems they are facing.

In this regard Sadc should establish a mechanism on the ground in order to seize the momentum for a negotiated solution.

4. To appeal to states and all parties concerned to refrain from any action that may negatively impact on the climate of dialogue.

5. In the spirit of all Sadc initiatives, the AU remains convinced that the people of Zimbabwe will be able to resolve their differences and work together once again as one Nation, provided they receive undivided support from Sadc, the AU and the world at large.

V: What is to be done?

An appeal and petition to Sadc to play its role in the face of another disputed election in Zimbabwe.

We believe that Zimbabwe has again reached the Lancaster House moment, the occasion on which to get back to the drawing board, reflect on a difficult two decades of conflict and embark on the path towards a Comprehensive Political and Economic Settlement.

Accordingly, on 7th September, 2023, a resolution of the combined meeting of the is a Sapes Trust and the Platform for Concerned Citizens (PCC) launched the following Petition to the Sadc Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Co-operation:

Once again a Zimbabwean election fails the test of credibility. However, the 2023 harmonised elections have failed the test so comprehensively that even the reputable regional and international observers are for once are in agreement that this

election has failed. The main opposition and many civil society organisations have condemned the election, as have many ordinary citizens.

The only response can be to declare the elections null and void, but then what should be done?

By any measure the Zimbabwean government since 2017 has shown no ability to reform, either politically or economically, and to create the conditions that could lead to an election that is free, fair, and credible. The coup in 2017 did not usher in a new dispensation but a continuation of the kind of governance that has led to the 2023 result.

There needs to be new way to resolve the crisis that this election has now deepened further, and not in the way that the crisis of 2008 was managed.

The way forward must be bold and innovative, recalling the manner in which the Rhodesian crisis was dealt with. This must require the following:

● The establishment of an Eminent Persons Group, tasked with negotiating the establishment of a Transitional Government, composed of political parties and other major citizen groupings.

● The negotiations must be broad-based, including political parties, civil society, churches, labour, women, and other citizen groupings.

The Transitional Government should set up with a clear and specific set of reforms that must be achieved, which should include:

● The resolution of the coup and the amendment to the Constitution allowing untrammelled military interference in civilian affairs.

● Full adherence to constitutionalism, the rule of law, and human rights.

● The reform of critical state institutions.

● The stabilising of the economy, with a pro-poor emphasis.

● The establishment of a sovereign fund to ensure the country benefits form Zimbabwe’s bountiful resources.

Complete overhaul of all the election machinery and legislation to ensure that the election that follows the period of the Transitional Government will lead to an election that meets regional and international standards.

This is the only way forward to resolve the crisis, and we call on all Zimbabweans, in the country and in the diaspora to support this petition, and we call on Sadc — through the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security — the AU, and the international community to support and scaffold this.

Ibbo Mandaza and Tony Reeler Co-Convenors (PCC)

By September, 2023, the petition has mobilised 80 000 signatures, with plans to officially elevate the document into the national programme on the back of a meeting, to be held in Harare on 5 August, 2023, in which the totality of civil society, trade unions, churches, professional and other lobby groups at home and in the diaspora – will press towards a Comprehensive Political and Economic Settlement in Zimbabwe.

In appealing to both Sadc and the AU, the Petition is recommending the appointment of the Eminent Persons Group, possibly of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, Jakaya Kikwete of Tanzania and Kgalema Motlanthe of South Africa, as the facilitation and mediation agency through which Zimbabweans at home and abroad can find each other and hopefully have a traditional government, or something similar, and charged with a Political and Economic Reform Agenda before the next elections in Zimbabwe.

In this regard, we have also solicited the support of the Coalition for Dialogue on Africa (CoDA), a joint venture of the African Union Commission (AUC), the Africa Development Bank (AFDB) and the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), and chaired by President Obasanjo, to assist Zimbabwe in this dialogue towards a resolution of the crisis in Zimbabwe.

And through the occasion of this Public Lecture, this is to appeal to the ANC and its government to pursue what Fikile Mbalula referred to in his email to David Masonda on the 6th of September, 2023, as the “delicate engagements regarding the situation in Zimbabwe.”

If the latter objective was indeed the reason for the apparent “unceremonious” cancellation of this lecture on 7th September, to this day, then I plead with you all that the ANC Secretary-General be forgiven, in the sincere expectation that South Africa itself in particular, Sadc and the AU, are indeed engaged with the crisis in Zimbabwe.

About the writer: Professor Ibbo Mandaza is a Zimbabwean academic, author and publisher. He is co-convener of the Platform for Concerned Citizens (PCC) which has sponsored a petition that has been forwarded to the chair of the Sadc Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation, as well as to the chair of the AU and the international community in general.

Mandaza presented this public lecture at the OR Tambo School of Leadership in South Africa on 28 September.

You may like