News

The rise and fall of the MDC: Winners, losers and neutrals

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksAS Zimbabwe approaches crucial by-elections in March, which will test the strength of main contestants while determining the authentic opposition, there is no denying that the MDC, which has posed the most formidable threat to Zanu PF for two decades, is now on its deathbed.

OWEN GAGARE

It faces an existential threat: extinction. It has run its course. Reached a dead end. Its demise will be a tragedy for democracy, yet an opportunity for reconfiguration, re-alignment and renewal of pro-democracy forces.

Formed in 1999 primarily by trade unionists led by its late founding leaders, fronted by Morgan Tsvangirai, Gibson Sibanda and Isaac Matongo, among others, the party was a broad church — with a wide range of ideological beliefs, values and opinions as well as competing interests — which included academics, professionals, particularly lawyers, civil society organisations and students, along with white commercial farmers who were an important constituent part.

Although rooted in local political conditions and a product of its environment, the MDC also had huge foreign support and backing. That is be[1]yond reasonable doubt.

The undertaker

The MDC has virtually collapsed with MDC-T leader Douglas Mwonzora, masquerad[1]ing as leader of the now defunct MDC-Alliance formerly led by Nelson Chamisa, playing the role of undertaker.

Mwonzora, aided and abetted by Thokozani Khupe, now his new rival, presided over the destruction of the MDC. Tsvangirai, Sibanda and Matongo, among others, and hundreds of MDC members and activists who died at the height of political combat with the late former president Robert Mugabe, who led Zanu PF, must be turning in their graves.

To understand the reasons why the MDC has all but collapsed, one needs to look at the role of ideology in politics and society, as well as political ideas and movements. Aristotle believed man was a “political animal” because he is a social creature with the power of speech and moral reasoning.

Hence it is evident that the state is a creation of nature, and that man is by nature a political animal. And he who, by nature and not by mere accident, is without a state, is either above humanity, or below it; he is the “tribeless, lawless, heartless one,” whom Homer denounces — the outcast who is a lover of war; he may be compared to a bird which flies alone.

Being political creatures, people have ideological beliefs, even if those may not be coherent, be they liberal, socialist or conservative, for instance. Ideological constructions are not rigid; they are variegated, complex and overlap — sometimes confused and confusing.

Left, centre or right?

The MDC was ideologically and dialogically mixed, complex and muddled. Although it had labour roots, its funders, white farmers, business community and foreign governments and foundations, had different and competing ideological perspectives and agendas.

While it often purported to be a social democratic party, it never practiced social democracy or was close to socialist, social democratic and labour parties.

It worked with parties ranging from social democratic to conservative; they were at home with Tony Blair and his New Labour party as they were George Bush and his Republican Party. They transacted — sometimes literally — with both; with institutions like the Westminster Foundation in the United Kingdom and the Republican Institute in the United States.

While the MDC was ideologically weak, fluid and unclear, torn apart by interests of its left social base and the right constituting its funders, with pragmatism sometimes as its approach, some modern political thinkers have argued that ide[1]ology is dead, that no one believes in it anymore, and that conflicts no longer have an ideological basis as they were before the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dall of the Berlin Wall.

The MDC was initially funded by white farmers who opposed Mugabe’s radical and unstructured land reform (some television footage showing donations by farmers provided propaganda fodder to Zanu PF and Mugabe) and that created internal tensions, dramatised by Munyaradzi Gwisai’s quitting of the party.

Drawing on this, it is clear that the changes in the structures and means of production as a result of the changes in the accumulation model and forms of employment in the country, particularly land reform and rapid informalisation of labour, had a number of effects.

As Brian Raftopoulos from the Centre for Humanities Research at the University of the Western Cape, and Solidarity Peace Trust, put it, the changes severely eroded the structural basis for labour and opposition mobilisation in a more informally constituted economy, in which the discipline and modalities of formal organisation built up by a once formidable labour movement were lost to the different rhythms of survivalist opportunism endemic in the more precarious conditions of informal livelihoods.

In the words of Hammar et al. (2010), as cited by Raftopoulos, the crisis of displacement that has characterised the historic upheavals in the Zimbabwean economy has reshaped patterns of production, accumulation and exchange, reconfigured state power, and led to conflicting claims and obligations. One might add that the kukiyakiya (wheeler-dealing to get by) survival strategies that have come to constitute a dominant form of social relations in the informalised urban area (Jones, 2010) have emerged as a result of the suppression of the more disciplined and public forms of or[1]ganisation associated with the labour movement.

But the bottomline remains that the MDC’s identity, policies and programmes were unclear or muddled from an ideological standpoint. Personality cult and clashes It was Karl Marx who said men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.

The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionising themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in or[1]der to present this new scene in world history in time-honoured disguise and borrowed language. Claude Adrien Helvétius puts it succinctly: Every period has its great men, and if these are lacking, it invents them.

The phenomenon of the personality cult has been studied across a variety of disciplines and from numerous hypothetical and research perspectives.

While Tsvangirai started as a humble servant of the MDC, he was fast elevated by those around him, exercising collaborative agency to a person[1]ality cult status through the deliberate creation, projection and propagation of a godlike image.

Through lionisation, hero-worshipping and deification, as well as associated political religion, he became larger-than-life and towered over the MDC. The party became synonymous with him. Holding a different opinion from him became tantamount to treason, attracting swift and harsh punishment from his loyalists.

The internal splits

This inevitably created factions, infighting and clashes within the party that culminated in the 2005 first split, with Sibanda and secretary-general Welshman Ncube leading a breakaway party which called itself the MDC.

That forced Tsvangirai to call his faction the MDC-T, which is the shell which Mwonzora is currently holding onto. Khupe used that brand to contest the 2018 elections and lost while Mwonzora was still at the MDC-Alliance.

They then fought over it following a court judgment which found that Chamisa was not the legitimate party leader and called for congress within 90 days. That congress was held in December 2020 and Mwonzora defeated Khupe amid chaos and rigging.

The MDC split over participation in senate elections that year had undertones of identity politics and ethnicity, the bane of Zimbabwean political discourse and practice. The split was acrimonious. There was serious polarisation, name-calling, and character assassination, as well as violence and brutality.

That badly dented the MDC’s image and reputation. Tsvangirai also began to be seen as a dictator-in-the-making. The split crippled the MDC and Tsvangirai hit rock bottom after a comprehensive defeat in the 2005 elections.

Prior to that, the MDC had performed dramatically well in the June 2000 parliamentary elections and the 2002 presidential poll. However, in March 2007, before the 2008 synchronised general elections, Tsvangirai and other pro-democracy activists, including National Constitutional Assembly leader Lovemore Madhuku and former MDC (Ncube’s formation) leader Arthur Mutambara, were viciously attacked and seriously injured by police as one of his supporters was shot dead in an anti-government demonstra[1]tion in Harare.

That sparked widespread outrage at home and abroad. It revived Tsvangirai’s political fortunes. This culminated in Tsvangirai defeating Mugabe in March 2008 before the veteran dictator fought back through intimidation and violence led by the military in a runoff in June that year. Tsvangirai pulled out of the election, citing brutality.

The move further divided the MDC-T. Chamisa, leader of the current main opposition Citizens’ Coalition for Change (CCC), another MDC offshoot which emerged on 22 January 2022, supported Tsvangirai, while some party stalwarts such as the late Roy Bennett and Innocent Gonese did not.

“There is a huge avalanche of calls and pressure from supporters across the country, especially in the rural areas, not to accept to be participants in this charade,” Chamisa said at the time. Bennett said while the June 27 runoff would not be free and fair, it was critical to stand against Mugabe.

“On the backdrop of that we have to compete in these elections to show the total illegitimacy of them,” he said. Gonese, the MDC’s secretary for legal affairs, agreed with Bennett.

“People are saying despite all that we should not withdraw and we also believe withdrawing will not solve anything,” he noted.

GNU and MDC demolition In the aftermath of the disputed 2008 presidential election, a Government of National Unity (GNU) was formed between Mugabe’s Zanu PF Tsvangirai’s MDC-T and the MDC led by Mutambara, which had supported former ruling party stalwart Simba Makoni and his Mavambo in the elections.

Using the Gramscian concept of “passive revolution”, Zimbabwe’s democratic forces become part of a passive revolution through two processes, Raftopoulos wrote. In one part of this configuration, notwithstanding the electoral popularity of Tsvangirai’s MDC, the repressive anchor of the Mugabe regime, itself pushed into a negotiated settlement by a variety of factors, largely shaped the contours of this settlement, forcing the opposition to adjust to Zanu PF’s reconfiguration of the state and its relations to capital from above.

Moreover, Zanu PF had carried out this manoeuvre under the cover of the regional body, it[1]self- constrained by its own limitations. In another part of this conjuncture, the control of an import[1]ant tool of leverage for change in the country’s political relations by external forces has placed the opposition and civic forces in a subordinate role to broader global agendas on political and economic change.

In that context, the politics of the opposition and civil society groupings could be understood as being in defensive mode, fighting to institution[1]alise forms of politics that could establish a broader basis for imagining and carrying out alternative political visions.

Moreover, the MDC-T in particular has had to adapt its political positioning to the imperatives of the Global Political Agreement, the politics of Sadc, and the demands of its supporters in the West. In that field of force, the persistent calls for new legitimate elections were understandable, but clearly faced enormous odds.

Finding a way through the problem remained a complex challenge that involved not just an electoral strategy but a broader development vision. As the parties pushed reforms, a process Mbe[1]ki had started way back in 2007, amid growing suspicions among them, Tsvangirai found himself closer to Mugabe and isolated from his top lieu[1]tenants like former finance minister Tendai Biti who feared the old dictator wanted to draw the MDC closer and destroy it.

Tsvangirai started enjoying power or proximity to it through close association with Mugabe, including drinking tea with him, and the trappings of office and patronage such as getting a big house from the state.

By the end of the GNU, Tsvangirai’s relations with Biti were strained significantly, especially over the new constitution-making process and concessions in various contested issues. Tsvangirai had been significantly compromised despite his popularity. When Mugabe, indicating right, swiftly turned left on his return from the Maputo Sadc summit on 15 June 2012 and railroaded the country to the 31 July 2013 elections, Tsvangirai and the MDC could not figure out what hit them. Amid a rigging plot by Israeli security outfit Nikuv, Mugabe won 62% of the vote to claim a sixth term as president, and was sworn in on 22 August.

Tsvangirai finished second with 34% of the vote. Zanu PF also dominated the parliamentary election, winning 196 seats. The MDC-T was buried under a landslide.

The 2014 split

After the 2013 elections defeat, which cost the MDC domestic and international support as its former allies, including friendly voices like British world politics professor Stephen Chan, attacked its organisational incapacitation and incompetence, infighting intensified. In their book, Why Mugabe Won: the 2013 Elections in Zimbabwe and their Aftermath, Chan and Julia Gallagher were ruthless against the MDC.

They said Zanu PF and Mugabe’s victory left the MDC battered and in disarray as election post-mortems predictably led to recriminations and another split in the party.

“How did it happen? Was this another instance of Mugabe and Zanu PF stealing an election through what some in the opposition claimed was a potent combination involving a sketchy voters’ roll with 100 000 centenarians, ‘assisting’ voters, turning away over 300 000 voters, bussing people into key races, and intimidation, though with less overt violence?” the authors asked.

“Or, did the wily politician win the election fairly, as Zanu PF claimed and as was accepted, with misgivings, by observer teams from the Southern African Development Community (Sadc) and the African Union?” Chan and Gallagher challenged the rigging claims, suggesting instead that Mugabe and Zanu PF won credibly, aided by some “judicious rigging” and a healthy helping of ineptness on the part of Tsvangirai and the MDC.

Chan and Gallagher pointed to several conditions — the legacies of colonialism; memories of the economic collapse of 2007-08 and the horrific election violence of 2008; Mugabe’s continued towering presence in Zimbabwean politics; Tsvangirai’s heroic, if flawed, challenge to Mugabe; and an evolving state-society relationship marked by simultaneously hopeful and ambivalent political attitudes — as critical in shaping the outcome of the 2013 elections.

In addition to all of these conditions and factors, a key claim in this book is that going into the 2013 elections the MDC ran a haphazard campaign. For Chan and Gallagher, the MDC was weakened during the coalition government. To begin with, participation in the coalition undermined the MDC’s most potent argument, one “rooted in the idea of its differences from Zanu PF, one of which was the idea of probity in government” (p.57). Second, key members and resources of the MDC were directed towards participation in the coalition government, resulting in fractured and weak party structures. As a consequence, the party lost discipline and capacity, both of which affected its campaign and ability to connect with voters in the 2013 elections.

While the MDC seemed to have been desta[1]bilised and decentred by participation in the coalition government, Chan and Gallagher contend that Zanu PF took advantage of the GNU to re[1]connect with its supporters.

Bound and united by the ideological construct of “patriotic history”, they suggest that Zanu PF fashioned a campaign that strengthened its grass[1]roots party structures among the rural populace and offered middleclass voters, long core supporters of the MDC, the possibility of material gains through its indigenisation programme.

“The outcome of this effort was that Zanu PF ran a ‘professional and committed campaign that involved a substantial voter registration drive, effective party mobilisation and a carefully crafted re-seduction of the Zimbabwean electorate’ (p. 71). Little wonder then that Freedom House survey results of voter intentions in 2012 pointed to real gains in support of Zanu, survey results that, curiously, the unfocused MDC discounted.”

Consequently, on 20 November 2013 Biti announced he would be opening a new law firm specialising in international finance law and domestic constitutional issues. In 2014, he fell out with Tsvangirai and left with Elton Mangoma and others to form a break[1]away party, MDC Renewal. The party quickly split and Biti formed the People’s Democratic Party, while former Energy minister Mangoma established the Renewal Democrats of Zimbabwe.

Prior to that, MDC founding senior leader Job Sikhala had formed his own splinter party called MDC-99 in 2010. This means there were many MDC forma[1]tions and manifestations in 15 years: The original MDC, MDC-T, MDC (Ncube’s formation), MDC-99, MDC Renewal Team, People’s Democratic Party and Renewal Democrats.

Using his personality cult, Tsvangirai during the 2014 party congress blocked Chamisa as the popular choice for secretary-general and imposed Mwonzora. Khupe was elected vice-president. Two years later, Tsvangirai tried to correct his mistake by appointing Chamisa as one of the two more vice-presidents together with Elias Mudzuri. The decision further fuelled divisions and internal strife. It ultimately became a ticking time bomb within the party.

When Tsvangirai died on 14 February 2018, the powder keg exploded as Khupe, Chamisa and Mudzuri battled to succeed him. Chamisa seized control of the party and a further split erupted. Khupe remained with the name MDC-T, while Chamisa moved on to form the MDC-Alliance. After the 2018 election in which Khupe’s MDC-T performed badly and lost dismally to the MDC-Alliance, Mwonzora waged war on Chamisa.

He took him to court and won, seized the party headquarters and other properties and then claimed its legacy. After defeating Khupe at the MDC-T December 2020 congress, Mwonzora sought to destroy the MDC-Alliance through recalls of elected officials, taking over state finances due to the party and later claiming the name MDC-Alliance. In the end, Chamisa formed the CCC and left Mwonzora with a shell. That almost certainly marks the end of the MDC, although the March by-elections and, most importantly, the 2023 general elections, will determine that.

The winners

Zanu PF emerges as the biggest winner in many ways after fighting the MDC tooth and nail for two decades to destroy it. Mwonzora did in two years what Zanu PF under Mugabe and later Mnangagwa failed to do in 20 years, that is demolish the MDC for his own personal interest and on behalf of the ruling party. His collaboration with Zanu PF is now common cause.

However, this might be a pyrrhic victory or worse. The strategy might boomerang and lead to Chamisa’s vigorous rejuvenation under the ris[1]ing “yellow wave” as indications on the ground strongly suggest that a stronger party might rise out of the MDC’s ashes like a Phoenix in the form of CCC – the law of unintended consequences.

The neutrals

Some of the people who sacrificed body and soul — and toiled with their blood and sweat — are exasperated that the party, which became one of the biggest pro-democracy movements in Africa and with a rich legacy of fighting an entrenched authoritarian regime while trying to gain power to rebuild Zimbabwe, has been sacrificed on the altar of unbridled personal ambition and political expediency. Many people were beaten, maimed and killed on behalf of the MDC and yet it now seems their sacrifices were in vain as their leaders commit politicide in pursuit of personal ambition and power.

The blood of many innocent Zimbabweans was spilt during the MDC’s mortal political combat with Zanu PF. Neutrals hope that the blood of those who died in the struggle for change, which is flowing like a river below the surface, will water the tree of democracy and lead to a new Zimbabwe where they will properly be honoured and remembered .

The losers

By far the biggest individual loser in this political soapie is Khupe. She fought Chamisa and then Mwonzora viciously and lost dismally. All her efforts, driven by rage rather than political strategic thinking and calculation, have gone to waste. Yet Mwonzora, who has won his battle against Chamisa over the MDC brand, is almost inevitably going to eventually become a big loser as he will go down as the MDC undertaker, risking being judged harshly by the current generation and history itself.

The MDC-Alliance could well be a poisoned chalice for him, which is almost certain. Chamisa lost the battle for the MDC-Alliance to Mwonzora, but might gain new traction under the CCC. He remains probably the most popular politician in Zimbabwe today.

Mnangagwa won the prize of destroying the MDC as a brand, although his plot with Mwonzora might backfire. Yet without a doubt the biggest loser is democracy. When a big opposition party like the MDC — which at its height was a major democratic counterweight to Zanu PF and its failed authoritarian project — collapses, democracy is the loser.

You may like

-

Diaspora Praise Without Diaspora Rights Is Political Dishonesty

-

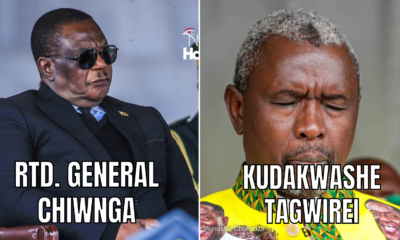

Tagwirei Leverages Money On Succession

-

ZANU PF’s Succession Politics, Is Not a Contest of Ideas but a Struggle for Access

-

Tagwirei at Zanu PF DZ meeting | Pictures

-

A Take On Chiwenga Succession Bid

-

PTUZ slam Mberengwa MP over abuse of office

1 Comment