I PLAYED a small part in the transition in 1980 from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe.

Eddie Cross

There were a number of reasons for this—I was chief economist in the largest agricultural group in the country along with the chief economist in government and the professor of economics at the local university. As such, we were used to try and prepare the new government for their responsibilities and then to guide the State in the run up to the first crucial donors’ conference.

We were emerging from 90 years of minority government by the small white community drawn mainly from the United Kingdom and South Africa. The previous two decades had been very turbulent—the break-up of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland; then the unilateral declaration of Independence; the banning of the nationalist parties and the imposition of mandatory United Nations sanctions supported by the closure of the Mozambique border. While all that was going on, we slipped down the road into a civil war and a counter insurgency programme that took our armed forces deep into neighbouring states.

I had been part of an initiative to try and persuade Ian Smith, the Prime Minister at the time, to appreciate he could not win a fight against the whole world. We drafted a memorandum that set out our thinking and sent it to him. He responded with a request for a meeting that was held in a private home in Harare. There were 35 of us in that group and we knew what we were talking about. He listened to our case and then responded that he saw no reason to change course, “we” were going to win. In six months, only seven of us remained in the country.

Three years later, in 1976, an international initiative led by the United States, Britain and South Africa, forced Ian Smith to accept what we had argued for in 1973. After that, the Smith regime was basically finished and although we fought on for another three years, the game was over and on Independence night I sat on the podium in Mbare, just behind the President of India, and watched the flags change.

In 1994, like the rest of the world I watched the dramatic changes in South Africa, again initiated from outside Africa but managed by local South African elements. Out of a chaotic process involving 19 political parties but with only two of any significance, a new South Africa was born and Nelson Mandela emerged as the first black leader. For me, the management of the transition had been the key to the outcome.

What were the key elements in these two transitions in Africa? They were many but I list the following as the principal features that resulted in a relatively non-violent transition to a new democratic era:

– Major international powers gave the problem their attention and had individuals with local knowledge and understanding advise them and, when necessary, they used their power to support change;

– They dealt with the parties to the situation who held real power in order to effect change irrespective of their own view of the situation;

– They worked with regional and continental leaders with influence and power; and

– They ensured stability while the changes were being implemented and did not attempt to influence the outcomes, even if in their own view they were less than desirable.

Even today I think it is astonishing that the United States gave so much attention to the conflict in Rhodesia. If you carefully examine the past four years of the Donald Trump administration, you will soon discover that Africa, south of the Sahel, hardly exists. But in 1976, the US Secretary of State, using all his immense influence and power came out to South Africa and broke the back of Rhodesian resistance with the help of South Africa whom he had persuaded that this was in their essential long-term interests.

Britain, with its in depth knowledge of Africa, played an essential role in both resolving the conflict in Rhodesia and then in South Africa itself. The British Foreign Office was the manager of the process (some would say the manipulator) and brought to bear their immense knowledge and expertise in all matters to do with Africa. But when it came to issues of real power and reach, the US came to the party. At one stage when Zimbabwe was desperately short of food, the US provided the basic needs for 70 % of the population. Without such an intervention, the situation would have spiralled out of control.

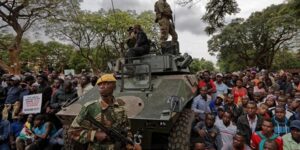

After 37 years of a Mugabe dictatorship, one which had deteriorated by 2017 into a quasi-military government operating through a junta who held real power, elements in the Mugabe regime rebelled and, with the assistance of the professional army, replaced Mugabe with a close associate in the form of Emmerson Mnangagwa.

A full stocktaking of the Mugabe regime has yet to be taken, but he was responsible for a number of programmes, some of which have been officially defined as genocide. Certainly, he crushed all dissent, outlawed opposition both in the country and in Zanu PF. When he was overthrown, the whole country celebrated.

The new President made it clear from day one that he wanted to put the country onto a different path. He wanted to re-engage the international community, he wanted all Zimbabweans to work together in charting a new path forward. He wanted to stabilise the economy and get the country growing rapidly with the goal of transforming one of the poorest countries in the world into a middle-income state.

It was clear to me that we were into another dramatic and historically significant transition. The problem was that he over-promised and under-performed. Was this his fault? I do not think so, it was essential to set out clear goals and objectives for the immediate future. The problem was that he did not have the resources for the task and he led a divided house. He was in every way, in political terms, a minority leader of a bankrupt state. The election helped but his own record did little to give credence to his claim that he actually won the election (I think he did—by a clear margin).

But, to his credit, he has stuck to his guns and implemented what he called in 2018, the Transitional Stabilisation Plan (TSP). This ambitious programme of reform and change was crafted before the election but only released afterwards. It embraces all aspect of the new Zimbabwe including political and economic reform as well as institutional changes.

It is now two years since that time and I sat in on a review about 3 weeks ago of the TSP presented by the Minister of Finance. It took him three hours and at its conclusion he stated that in his view, the majority of the stated objectives had been achieved. I was blown away, but noted with dismay, that only one diplomatic mission had sat in on the presentation. In my experience I have never participated in a review of such a wide-ranging public programme where the great majority of the targets have been satisfied.

To me it is clear that real progress has been made. What is not so clear is whether local business and local politicians as well as our 80-odd foreign diplomatic missions here have a similar understanding. If not, then they are in danger of missing out of an opportunity to help this tiny African state get back on its feet and find its way, after years in the wilderness, into the future.

About the writer: Cross, a former opposition legislator, is a member of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s Monetary Policy Committee.