Opinion

LONG READ: How Mnangagwa has consolidated his grip

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawks…Grab power by any means

DR ALEX MAGAISA

FOR a man who waited 37 years as an understudy, the past three-and-a-half years have been an anti-climax of enormous proportions.

One might have thought that he used the long period of political apprenticeship to identify the errors to be avoided if ever he got an opportunity to lead. However, nearly four years since grabbing power in a coup that toppled his long-time boss, Robert Mugabe, Emmerson Mnangagwa has struggled to uplift Zimbabwe from the depths of poverty, and citizens remain under the yoke of political repression. The average Zimbabwean is no better today than he was when Mnangagwa took office in those heady days of November 2017.

Three and a half years ago, Mnangagwa was forced to flee Zimbabwe in the dark of the night. He had just been sacked by Mugabe from his position as co-Vice President. The sacking followed a dramatic period during which Mnangagwa was the subject of verbal attacks at political rallies. The charge was led by Mugabe’s wife, Grace who was in her element. The end seemed nigh but the sacking turned out to be Mugabe’s greatest undoing. It was the trigger that propelled his own downfall. It sparked a chain reaction of events that saw the military generals disobeying his command and defying the Constitution to carry out a coup. Mugabe had stayed in power for so long he forgot that he was propped up by the military and his hold on power was only assured if he did not threaten their economic interests.

When he took the gap, Mnangagwa made a confident, if haughty undertaking. In a memo from his temporary lair, he made a promise to Zimbabweans that he would return in two weeks to lead them. The true story of what happened then has not yet been told with sufficient authority and objectivity. There are too many hagiographies that glorify Mnangagwa and other critical commentaries from the wounded. Perhaps one day there will emerge a more objective and authoritative account of events. But what is clear is that the plan to carry out a coup was already in existence long before it was executed and Mugabe had ignored the threat, believing that his lieutenants were loyal to the end. The sacking was a rare act of political misjudgment in Mugabe’s long career. It was the spark that lit the powder-keg.

And so Mnangagwa returned home in a feat of glory. It all fitted in perfectly, giving the impression that the entire story had been pre-scripted. The generals had done their job. They had jettisoned Zimbabwe’s longstanding ruler, but in the process, they had also vanquished a faction that was vying to succeed Mugabe, paving the way for Mnangagwa’s faction. The nation had watched from the sidelines as Mnangagwa’s Lacoste faction battled it out with the G40 faction whose principal face was Grace Mugabe. Mnangagwa took the prize but it was the military that made him.

The coup had helped him achieve the first step in consolidating power: Grab Power by Any Means. But getting to the helm is one thing. Maintaining power is a different proposition. This article examines how Mnangagwa has used the first three and half years to consolidate his power.

Sanitize dirty power

Mnangagwa knew that the method by which he got into power was unclean. Propaganda labels such as “military-assisted transition”, which gullible media, politicians, and even diplomats latched onto were not enough to launder the coup. Some people, even in the opposition, thought that there would be a power-sharing arrangement after the coup. The removal of Mugabe was supposed to usher in a new era of cooperation between like-minded forces. This was a gross misjudgment, especially by the opposition which underestimated Mnangagwa’s ambitions. He had no intentions to share power with anyone. What stood in the way of power was Mugabe and the faction that was opposing him. Once they were removed, the path to power was clear.

If the parties that united for the coup had arranged to suspend elections, Mnangagwa’s ride might have met with very little opposition. But apart from the ambition to exercise exclusive rule, the coup was a blot on his leadership. The coup had left a hangover of illegitimacy which weighed heavily on him. He thought an election would sanitise his ill-gotten power.

Several factors gave him confidence that it would be a smooth ride. The popularity of the coup among Zimbabweans made him too confident that the people liked him. He overestimated his popularity and did not realize that people were more excited by the departure of Mugabe who had seemed unremovable after 37 years in office. He wrongly conflated the popularity of Mugabe’s removal with the reception of his ascendancy to the top.

The death of Morgan Tsvangirai, the popular opposition leader who had given Mugabe sleepless nights, led him to believe that the MDC would be a much-diminished opponent. He was also wrong on this count. The youthful Nelson Chamisa, who succeeded Tsvangirai went on to win more votes in a presidential election than his illustrious predecessor. It was even more remarkable because he did so on a shoe-string budget and with very little time to campaign since Tsvangirai died in February with the election just 5 months away.

In the end, the election brought more trouble than he had anticipated. It did not resolve the legitimacy question, especially as his main rival refused to give the elusive loser’s consent because he maintained that the election had been rigged for Mnangagwa. This dispute has hung like a cloud over Mnangagwa’s first term even after the Constitutional Court ruled in his favour. If the election was supposed to launder his power and confirm his legitimacy, it was largely a failure because the stain could not be washed off. The election itself was never going to be anything other than a charade. The generals had not taken the audacious step to carry out a coup in order to give up the power just a few months later. The purpose of the election was to sanitize the power-grab, but sadly for them, they retained power but failed to win the legitimacy they so coveted.

Buy the opposition

The easiest way to consolidate authoritarian rule is by weakening the opposition. All authoritarian rulers in history have used several methods to eliminate the opposition. They can ban all opposition and create a one-party state, but this method lost currency in a previous era. However, this has not stopped authoritarian rulers from still trying to establish a one-party system of government. They simply make the practice of opposition politics impossible. If they can’t ban the opposition, they simply control it.

Past dictators have killed their opponents. Others have jailed them. Harassment is a common strategy. The law is weaponized against opponents. Selective application of the law is a common weapon. They also try to bankrupt the opposition party, a method of financial asphyxiation to snuff the life out of opponents. When they identify fault lines, they use the divide and rule strategy by sponsoring factions within the opposition. They can infiltrate the opposition to create or exacerbate conflicts and divisions, in addition to extracting strategic information.

In a previous article, I have explained how the Mnangagwa regime has made use of the twin strategies of coercion and co-optation against the opposition. If you cannot repress them, bribe them to your side. Opposing an authoritarian regime is tiring and costly for individuals. For the ruling party, chasing the opposition is like a predator chasing prey. The predator targets the weaker members of the herd and goes after them. After some time, the isolated and weary targets lose their legs and the predator pounces. The last three years has seen many weary opposition warriors fall prey to the bite of the crocodile. Their future is now in Zanu-PF, not in the opposition. They are gone and they will be more vicious towards the opposition than the original Zanu-PF members.

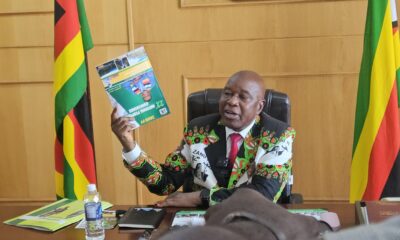

Mnangagwa has used several of these methods in his quest to eliminate the threat of the MDC Alliance led by Nelson Chamisa. Just this week, he handed over brand new vehicles to members of the Political Actors Dialogue (Polad) which is made up of several of the losing candidates of the 2018 election. Just a few weeks ago, one of Mnangagwa’s cronies, Kuda Tagwirei handed over 5 vehicles to the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP), a move that raised eyebrows as it increases the risk of capture of the law enforcement agency by private actors. Why would the government have no money to buy the police service vehicles but have enough to buy 20 vehicles for political upstarts whose only qualification is their ambition to become president?

Besides, the gift of vehicles to Polad members is arguably a violation of the Political Parties (Finance) Act which regulates state funding of political parties. None of the parties whose leaders were gifted a vehicle qualify for political party funding under the law because they did not get the requisite minimum 5% of the total votes at the election.

But Mnangagwa has simply circumvented this by rewarding members of the Polad, a structure that he created in the aftermath of the controversial 2018 elections.

For their part, members of Polad have accepted the gifts, to which they believe they are entitled. People ask why Mnangagwa does not prioritize more important social needs during a pandemic, but for the authoritarian mindset, there is no greater priority than to control the opposition. When he created Polad, the idea was to dilute the voice of his main rival, Nelson Chamisa. He wanted to drown him in the sea of political chancers and pretend that he was engaged in dialogue with the opposition. Chamisa rejected this proposition.

Other opposition leaders that have a better sense of political decency like Nkosana Moyo, Noah Manyika, Joyce Mujuru, Daniel Shumba, and Elton Mangoma saw that Polad was a charade. They recognised that it was a marionette show in which Mnangagwa was the puppet-master wisely decided to keep away from it. But there was a desperate lot that was eager to join and sit within sniffing distance of the gravy train. Their role was to sanitize the regime and give the world a false impression that there was a working arrangement between Mnangagwa and the opposition. Mnangagwa made them feel important and they in turn began to believe the lie.

Every authoritarian regime has a set of enablers, the so-called useful idiots. Polad is the platform and they have demonstrated excessive eagerness to play that role. The vehicles represent an incentive to continue in the regime-sanitisation project. The fact that they will be surely punished by voters at the next election does not bother them. They will be ready to play their role to sanitize another rigged election and to join another Polad where they will be handsomely rewarded again. If all else fails, they will just take the direct route taken by the likes of Lilian Timveos or Obert Gutu to join Zanu-PF and wait for rewards. Gutu was rewarded with a role as a commissioner while Timveos got a board membership in a state-controlled entity.

As for the MDC-T led by Senator Douglas Mwonzora, it is just a matter of time before it formally joins Polad. But even if it keeps away, it has already shown its disposition toward the Mnangagwa regime. Its so-called philosophy of “rational disputation” is no more than a politics of appeasement whereby the MDC-T sees no evil, speaks no evil, hears no evil about Zanu-PF’s failure of governance and repressive politics. The minor party’s obsequious stance toward Zanu-PF is a quid pro quo for all the backing that the regime gave it during the battle for party representatives, assets, and funds against the MDC Alliance during 2020. It is heavily indebted to Mnangagwa and his regime.

Although Mwonzora and his party are sure candidates for severe punishment by voters at the next election, by then they would have served their purpose. Their politics is no longer about opposing or overcoming Zanu-PF’s misrule, no. Their raison d’etre is to oppose ZANU PF’s strongest opposition, the MDC Alliance and it is a role they have taken with the pleasure of a duck to water.

Since they have virtually no prospects of winning the next election, they are staking their future, not in an opposition victory but a future in which Mnangagwa and Zanu-PF remain in power. In that event, Mnangagwa will drop another lifeboat for them in the form of another Polad, diplomatic posts, or other public offices. For authoritarian rulers, the power of appointment is a handy accoutrement in a system of patronage where sycophants and enablers are rewarded.

Keep the military sweet

Mnangagwa is eternally indebted to the military because without them he would not be in power. It was the military that toppled Mugabe in 2017, creating an easy pathway to power for Mnangagwa. If the putsch had not happened, Mnangagwa would probably be living in exile, with his nemesis the G40 faction in charge of the state. For that reason, Mnangagwa knows he must keep the military sweet.

I have argued before that the coup fundamentally reshaped the structure of the state, confirming in all but name the military as the fourth arm of the state apart from the executive, legislature, and the judiciary. Not only did the military establishment call itself the “stockholders” of the nation but the judiciary conferred a veneer of legality to the coup, endorsing the claim that the military had not violated the Constitution even though it had acted without its Commander-in-Chief’s authority. Any theorization of the Zimbabwean state that fails to consider this abnormality would be misdirected.

The military has stamped its mark by the deployment of military personnel to virtually every pocket of public power that is of strategic importance. To be sure, this militarisation of state institutions has always been a recurring feature, but it seems to have intensified after the coup as leaders of the coup exchanged their military fatigues for suits and took public office.

The body that oversees public procurement in Zimbabwe, the Procurement Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (Praz) has nearly half of its board positions occupied by military personnel. You would be hard-pressed to find a state-controlled entity that does not have a military presence. They are not only the eyes and ears of the military establishment, but it also guarantees them access to public resources. This ensures that both the institutional interests of the military and the individual interests of the deployed are catered for.

Another way is to guarantee the military establishment a large piece of the economic pie. Deployment into strategic national assets is one way but direct control of the means of production is another. This is achieved through critical sectors like agriculture and mining. Public programs like Command Agriculture have been hugely beneficial to politically exposed persons (PEPs). All the Mnangagwa regime must do is to avoid upsetting this arrangement. The regime protects their economic interests, and they protect the regime. The game-changer is if the regime begins to threaten the economic interests of the military establishment.

A good example is the Great Dyke Investments deal which was revealed by The Sentry report last month. It had long been known that the Zimbabwean military had a significant interest in GDI, a joint venture with a Russian company for the multi-billion-dollar platinum mining project. The project was struggling to get international financing because of the involvement of the military. Operating through its investment vehicle, Pen East (Pvt) Ltd, the military sold its stake to Kuvimba Holdings, a company in which significant PEPs are involved. But as The Sentry report warned, these off-budget deals for the military create a parallel power structure which may prove to be Mnangagwa’s undoing. His attempts to keep the military sweet may backfire if an independent and wealthy military discovers that it can push and fund its agenda independent of Mnangagwa’s executive.

Eliminate co-conspirators

Rulers that get into power through a coup might be grateful to their co-conspirators, but they do not trust them. They know that the co-conspirators are just as ambitious and may even be impatient to have their turn. The coup would have planted the seed and as the cliché goes, a coup begets a coup which means that one coup is more likely to be followed by another. The ruler must therefore guard against the risk of another coup, which would topple him. He must keep ambitious lieutenants on the leash. In extreme cases, co-conspirators are killed, or they meet suspicious deaths. In other cases, they are jailed.

Whether it is by the hand of nature or humankind, several individuals that were key to the success of the coup have succumbed over the intervening period. History will record that the coup was followed by a deadly pandemic that retired several influential figures. They include generals S.B. Moyo who was the face of the coup, Perence Shiri who headed the Air Force, and Paradzai Zimondi who oversaw the prisons. Another general, Nyikayaramba also succumbed to the pandemic.

Chiwenga, the man who led the coup, has been battling a mysterious illness that has taken him to several countries. This has led him to an embarrassing situation where although he banned health tourism, he is a regular and high-profile health tourist to China. The illness has not only debilitated him, but his pursuit of overseas treatment has also damaged his integrity and credibility. The recent death of the army commander, Edzai Chimonyo is another loss of an old comrade who was catapulted to the top after the coup. The demise of old comrades has not diminished Mnangagwa. It has strengthened his hand because it has enabled him to replace them with his own men. A post-coup ruler always needs men that are beholden to him.

There are other softer ways of keeping rivals at bay. One of the easiest ways is to use the power of appointment to deploy potential rivals far away from the seat of power, where they pose no threat. Mnangagwa has done this by appointing key figures to diplomatic missions. The general who also led the military campaign that killed six citizens and injured scores on 1 August 2018, Sanyatwe, was posted to Tanzania. Nyiakayaramba had been posted to Mozambique. While former opposition figures might see favour in being deployed as an ambassador, for ruling party stalwarts it’s a demotion. It’s like a first team player being loaned out to play in the lower league. That is what happened to Victor Metemadanda who lost his role as Deputy Defence Minister and Commissar of Zanu-PF when he was shipped out to Maputo to replace Nyikayaramba.

Build a personality cult

Most authoritarian rulers centre themselves in the national narrative and build a personality cult. Mnangagwa arrived late in the presidency and lacks the charisma and charm to build a personality cult. He does not have the gift of the tongue which makes listening to his speeches a trying experience. But this has not stopped him from trying. In just three and a half years there have been several hagiographies written to amplify his story. But the story has so many holes it leaks like a sieve. The narratives always sidestep gruesome episodes of his life, such as Gukurahundi in the 1980s where he had a starring role as Minister of State Security that oversaw the dreaded Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO). These omissions make the narratives vacuous and dishonest.

In recent months, his advisers have brought dubious characters to State House probably to boost his profile among young people who by most reasonable estimations are likely to play a significant role in the next election if they are registered to vote. Mnangagwa is probably fascinated by the way these pseudo-religious figures have mastered the art of building a personality cult. They have large followings of the gullible, and he probably hopes for some political osmosis by which this patronage might transfer to him. But as the cliché goes, there is no free lunch, and these megalomaniac characters milling around him are certainly milking their proximity to the highest office in the country.

The narcissism which drives this deification includes the re-writing of history in ways that centre Mnangagwa in the national narrative. Even otherwise noble ideas such as the honours system that is designed to honour individuals that have made outstanding contributions to society are contaminated by nepotism and conflict of interest. In the latest decree, Mnangagwa unashamedly awarded his wife a national honour which he calls the Order of the Star of Zimbabwe Gold.

One is reminded of the embarrassing episode in 2015 when the University of Zimbabwe granted Grace Mugabe a doctoral degree in very controversial circumstances. It is all the more disappointing because Mnangagwa came in with a promise to be different. In reality, there are more continuities than differences. Mugabe lurked behind the university. Mnangagwa has no regard for such formal niceties. He has gone a step further to personally hand his wife a national honour. He is simply raising the middle finger to the citizens and telling them he does not care what they think of him.

Control and weaken institutions

Authoritarian rulers do not like strong institutions because they get in the way of exercising power. Strong democracies have independent institutions that act as checks and balances on the exercise of executive power. However, authoritarian rulers prefer to exercise total power without any institutional oversight. One of the most important institutions is the judiciary, which is why judicial independence is critical. This is the reason why Mnangagwa has gone full throttle to control the judiciary by unlawfully changing the Constitution which is less than 10 years old.

Two big changes have been made to the judiciary, impacting its independence. The first was the change to the judicial appointments process from one that was open and transparent back to a procedure that is opaque with powers concentrated in the presidency. This gives Mnangagwa the power to control the composition of the judiciary. With control of the critical political referee, Mnangagwa can sleep easily.

The second method was amending the Constitution to allow the Chief Justice who was due for imminent retirement to retain his job for another five years. He did this by changing the Constitution to effectively raise the retirement age of judges from 70 to 75 years just a few days before Chief Justice Malaba was set to retire upon reaching the age of 70. It does not require a rocket scientist to observe that the Chief Justice is now in Mnangagwa’s debt. Without Mnangagwa’s lifeboat, Malaba would have sunk on a paltry package quoted in the weak Zimbabwean dollar. The irony was that in two previous judgments he had condemned litigants to receive their awards in the weak Zimbabwean dollar, but when it was his turn, he was unwilling to take it.

But it is not just the judiciary that has been severely compromised by these unconstitutional changes. While the constitution establishes the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission as an independent institution to fight corruption, Mnangagwa created his parallel structure housed in his office which he called the Special Anti-Corruption Unit (Sacu). It is a contradiction to establish an anti-corruption unit in an office that is potentially the epicentre of high-level corruption. It is as if Mnangagwa established the unit as a gatekeeper against the scrutiny of corrupt activities in his office. Such disdain for strong and independent institutions is part of the strategic agenda in which all power is centered in the presidency.

Conclusion

Mnangagwa is making use of all the rules in the dictator’s playbook – from weakening and eliminating both internal and external rivals to personalising power and weaking state institutions. He wasted a great opportunity in the first few months when citizens and the international community gave him the benefit of the doubt. Despite feigning to be as soft as wool, it did not take him long to show his true colours. If his co-conspirators thought he was just a seat-warmer, they misjudged his ambitions. If the charge against Mugabe was that he wanted to die on the throne, his successor is no different.

His biggest mark has been on the opposition, where co-optation has worked to his advantage. There were several weary individuals in the opposition, and he has managed to capture them. But he knows that his chief nemesis lies in the MDC Alliance. He will not stop until his goal is achieved. Know your enemy, says Sun Tzu, which is why the opposition would do well to go beyond the traditional rhetoric and understand the creature they are dealing with.

The challenge is to not only fully appreciate the structure and pattern of power under the Mnangagwa regime, but also to devise strategies to counter and overcome it. This is not to say the opposition has a duty to explain those strategies in public. That would be political naivety. Where in the world has a political party fighting authoritarian rule disclosed its strategies? To what end and to please who? But this does not mean the opposition must be distracted by sideshows. If the MDC Alliance judges itself against the MDC-Ts and NCAs of this world, it will be wasting precious time and energy.

About the writer: Dr Alex Magaisa is a lecturer at Kent Law School in Britain and former adviser to Zimbabwe’s late prime minister Morgan Tsvangirai.

You may like

-

New Army Appointments Bad News For Chiwenga Presidential Ambitions

-

ZANU PF’s Succession Politics, Is Not a Contest of Ideas but a Struggle for Access

-

Tagwirei at Zanu PF DZ meeting | Pictures

-

Zanu PF Annual Conference Review

-

Ziyambi’s brutal unpacking Mnangagwa’s Legal coup against Chiwenga

-

Mutsvangwa In Fresh Chiwenga Attacks

1 Comment