JOHN KELLEY

IT was a normal chilly winter’s morning at 6am on 6 June 1972, when 427 miners boarded their transport vehicles and lifts to take them deep down into the five kilometres of tunnel shafts at the Wankie (now Hwange) Mine No. 2 Colliery, known as the Kamandama, in the north-west of Zimbabwe, then known as Rhodesia.

More than 40 absentee miners had stayed behind, either through being sick or on holiday. Some had swapped their holiday dates with colleagues, which turned out to be a big stroke of bad luck for some and good for others – a saving of life, or a condemnation to death. There were to be many such stories emerging later.

As these unfortunate shift workers boarded their vehicles and lifts that day, they had no idea of the fate that awaited them.

Just after 10.30am, around halfway through that early shift, office workers and others on the surface felt a strong earth tremble underfoot. They thought there had been a minor earthquake, something occasionally experienced at the mine and surrounding area through the years.

But it soon became horribly clear that instead of a minor earthquake, a massive explosion of methane gas had ripped through the shafts, instantly killing every single one of those miners and throwing the entire mining equipment throughout the many shafts, including vehicles and steel girders, rocks and coal into a vast entanglement of bodies.

The immediate evidence of a disaster rapidly became clear to those above. A huge pall of black smoke spreading across the town and the countryside, spewing out in an ugly cloud from the entrance to No.2 Colliery. A further indication of the explosion’s immensity was a wrecked cable car which had been catapulted more than 50 metres from the mine entrance into some trees.

The story of Hwange mine goes back to 1893 when a tribesman reported finding “stones that burn.” This was followed up by a young German prospector, Albert Giese, who discovered that coal was to be found in great quantities buried deeply as well as near the surface through a considerable area not far from the Zambezi River.

Ultimately, in 1902 after sole mineral rights were claimed by the British South Africa Company and approved by the government, 6 600 000 tonnes a year were being extracted by 4 400 employees. “Stones” brought out were soon feeding the country’s industrial heating, farms and homes, with a high proportion left over for export earnings.

During the next 70 years there had been relatively few accidents and fatalities recorded. With its first-class ventilation system and careful safety measures, the mine created a good reputation, but always there was the underlying awareness that mining was a dangerous occupation.

The miners knew all about the ever-present long-term dangers of breathing coal dust, which caused the pneumoconiosis that shortened many lives.

It was also a generally unpleasant work routine to undertake every day down below. But beneficially the miners had established a strong community spirit in a supporting town, with shops, schools, clinics and sports facilities.

In a split second, however, all that had been ripped asunder as shown by that billowing smoke pall.

At this first evidence of a dreadful disaster, people came running to discover the worst and were horrified at what they saw and had some idea of what had happened below.

There was a stunned silence among a large and growing crowd as the dread of what had happened took hold. People then ran in shock from everywhere because down there were all those fathers, husbands, sons and brothers. But there was absolutely nothing they could do and they were kept well away from the mine entrance by officials and police. Before long came the sense that every miner had been killed, though many would never believe that.

Those unfortunate miners were a cosmopolitan team. There were 176 Zimbabweans, others from Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania, South Africans as well as Namibians, from Caprivi Strip and a Botswana national. Nearly all of them were between 20 and 35 years old and had left behind a large number of widows and young children, many of these to become destitute in the long period of confusion that followed.

It was the fifth-worst mining explosion in the long international history of coal and other mineral extraction enterprises worldwide in terms of fatalities. The worst recorded was at Benhixhu, China, in 1942 that claimed 1 300 lives. At Couriers in Northern Transvaal, 1906, a naked flame lamp ignited methane gas with devastating result and a recorded 1 009 miners were killed. And around Zimbabwe during 2019, a bad year, there were almost 100 deaths including five at Esigodini, 30 at Bindura, 13 near Mutare and among many casual and artisanal miners unrecorded.

Many “proto” (rescue) teams began to arrive at Hwange from neighbouring and other countries. Most were accommodated at the hilltop Baobab Hotel, outstandingly run by the country’s only woman manager, Queenie Slade. They immediately set about trying to rescue the victims, hoping without much optimism, to bring out survivors.

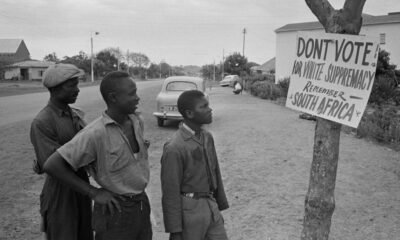

The first of these teams were local men and very soon the next team arrived from Zambia. They had said: “bugger sanctions and politics, these do not matter a jot compared to this. Those men down there are our fellow brethren”. They had crossed the border in great haste with President Kenneth Kaunda’s instant permission despite international sanctions.

For three days, the many following rescue teams joined the attempt, working in relays and at considerable risk to themselves while trying to penetrate the jumble of smashed machinery, bodies, boulders and coal. It quickly became apparent that their hopes were slim, if not at zero. Before long, they became aware of the great danger they were putting themselves into, either by roof rock falls or even further explosions. There were, in fact, three more. They nevertheless managed to get down 200 metres or so, but that was all. And they were now undoubtedly in very dangerous territory.

During this period a newspaper report stated that bodies were being brought out. This reckless false story prompted a great rush of local people anxious to get identifications and to desperately hope against all odds they would soon be given further and better news. Chaos resulted as they demanded further information. In fact, three bodies were eventually located and removed. But that was all.

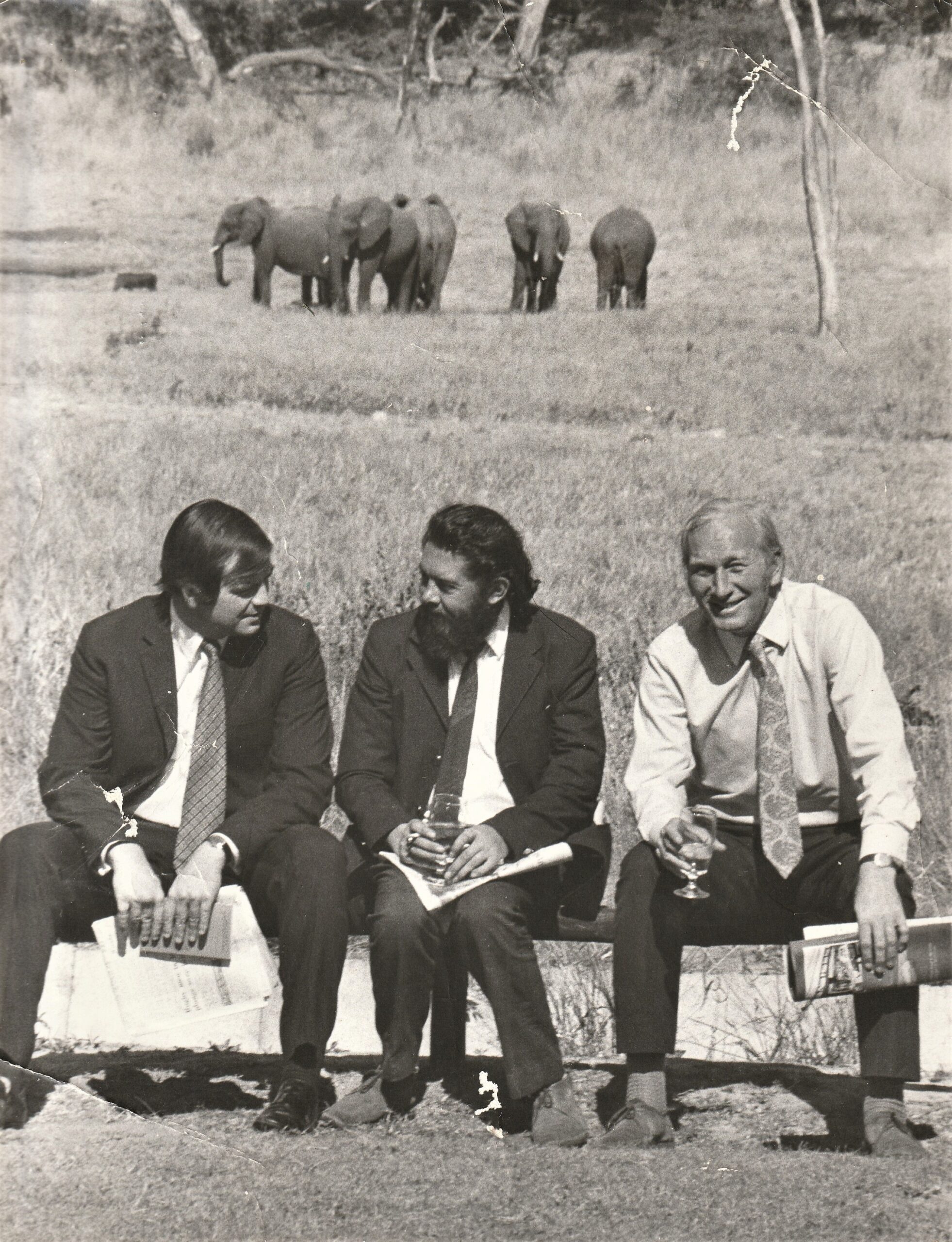

Enter into this mayhem myself as news editor designate of The Rhodesia Herald, Chris Reynolds, news editor of The Sunday Mail and photographer Johnny Woodruff, sent hurriedly to Hwange with the objective of carrying through proper and responsible journalism as well as repair the errant newspaper’s failing. Commendations and invitations to return at any time were later sent to the editors of both papers. The mine sent for 250 extra Herald newspapers for distribution.

We were flown to Hwange in a tiny airplane piloted by a woman, Gay Russell. She had to return from the runway to the airport building so as to retrieve her forgotten handbag which had been left behind. It was the only bit of humour for a long time to come.

After two days of reporting, we were in the crowded bar of the Baobab Hotel the next evening when Reynolds noted that Howard Vaughan, the Anglo-American Corporation public relations consultant, was not present.

Journalists from newspapers worldwide had no inkling. And so we quietly discussed his absence and notified Woodruff. Vaughan could only be down at the mine offices, we concluded, which meant something of significance was being decided, probably at a meeting of all management and proto leaders. And so we crept away from all the other journalists, using Queenie’s borrowed car, thereby discovering them in discussion under manager Gordon Livingstone-Blevins.

Vaughan spotted us peering through a window and came out to divulge that the decision had just been made to permanently seal off the mine as being too dangerous for any further rescue attempts, thus leaving all the dead miners entombed down below. He said he intended to circulate a Press release an hour or so after the meeting ended, when it had been drafted and approved. They were well aware of its significance.

And so Reynolds and I had an exclusive story well ahead of all our rivals. When other journalists eventually rushed for telephones after receiving Vaughan’s Press release, we had already filed.

There was more pandemonium among the populace as the decision became generally known. Women, especially, were beside themselves with renewed grief, shouting “No, no, you must try again.” Police were increased at the colliery entrance for extra security as this reaction was anticipated.

The focus now came down to a funeral and memorial service combined. It was attended by at least 5 000 people who came from up to 100 kilometres away. Some had even walked through the preceding night. It was a most moving ceremony, marked by the dignity of the great crowd as they conducted their traditional rites.

Politicians, church leaders of all denominations, mine management, traditional chiefs and headmen as well as people from various communities and miners built up into the huge crowd. The bereaved families, and also the miners who were not on that fateful shift plus hundreds of children, stood in stunned silence, the younger ones confused about what was going on. The service was conducted by various religious leaders, including primarily by a Methodist minister, the Reverend Bill Blakeway, who had been a prominent figure among distraught families in the disaster’s immediate aftermath.

The next Monday a large number of miners went back to work down Number Three shaft, even though they were highly sensitive to thoughts of danger. There was an incredible 85% turnout, which showed their great courage and dedication and was seen as a tribute to departed colleagues. Reynolds, Woodruff and I also went down with Livingstone-Blevins and mine captains and I had the dubious honour of setting off the first controlled explosions.

There were also more important decisions to be made. The primary one was to abandon deep shaft mining at Hwange altogether and concentrate exclusively on surface dragging with one massive piece of machinery.

This considerably reduced staffing requirements and also production levels. The future of the town was put into question. Increased unemployment levels had to be dealt with. Some newspaper assessments thought that the town might go into terminal decline.

After a massive investigation was instigated, a 109-page report of about 60 000 words was submitted months later to President Clifford Dupont. The additional report by Livingstone-Blevins of 42 pages was more readable and more clearly understood but neither report indicated the precise reason for the methane gas explosions, nor did they make recommendations.

But Livingstone-Blevins did record, however, that Hwange was not a “fiery” mine in terms of the mining regulations. Presumably he felt that the long-term safety record of the mine justified this observation, although at the time it seemed contradictory in the circumstances.

He also referred to two recently new section workings in No.3 colliery known as HE2 and HE3. But these were said to have unstable roofs and production was considered too low. So they were ordered to have their entrance points permanently sealed with explosion-proof stoppage material. However, this was never carried out and Livingstone-Blevins reported “and I don’t know why.” This seemed to reveal his suspicions that here might lie the root cause of the explosion. But only a suspicion.

A fiery mine is a term used by the government’s principal secretary of Mines. It defines “a gassy mine where gas ignitions and outbursts have occurred in the past and from which there is caused a danger.”

There was a great deal of confusion about Hwange’s obligations and responsibilities to workers following the disaster and many wives of the dead were left destitute or in dire circumstances for a long time. Right up to 2020 and no doubt beyond, more than 20 now elderly widows attend annually, by invitation, an informal ceremony at the mine. A great many donations were made through the years. Britain’s parliament decided on a small grant of £25 000, thus bypassing sanctions.

The British National Coal Board was quick to send out an expert to carry through a review of the disaster. He told me in an interview following his inspections that the mine did not have what is called “stone dusting”.

This means the establishment of large piles of crushed granite positioned at frequent intervals on shelving just under the roofing of shafts, designed to slow down any explosion. This is a common precaution at many mines globally. Noting its absence at Hwange, he commented: “If I had come here earlier, because of that failing I would have ordered the mine’s closure.”

After 50 years the memory of the disaster has slipped into history. But for a great many elderly miners, widows and the extended families of the men who lost their lives on that fateful day it remains a vivid memory.

*Author and journalist John Kelley emigrated from England to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, in the early 1960s, working for national newspapers and magazines. Later on he became a correspondent for major international news agencies and newspapers in addition to publishing and public relations.

He also broadcasted for Canadian national radio, Swedish Broadcasting and the American Broadcasting Company. After living and working in Zimbabwe for nearly half a century, Kelley now lives with his wife Barbara at Southsea near Portsmouth, England, still playing golf at the age of 91 and writing occasionally for The NewsHawks.