Opinion

Zimbabwe in 2023: There is great disorder, chaos under the heavens

Published

3 years agoon

By

NewsHawksWILLIAM JETHRO MPOFU

GEORGE Orwell wrote so much and so well that one day it became cause for a whole essay to explain to himself and the world why he wrote as such.

In the essay of 1946, Why I Write, Orwell recounts his reasons for writing that, “putting aside the need to earn a living”, included the search for fame, pursuit of literary beauty and power, the need to document history for posterity and, finally, political purpose or cause.

I can add we also write in the public interest, for the common good, for community service.

Writing for political purposes or causes includes, amongst other things, the need to unmask concealed truths, name some evils, and propose some directions for a specific polity.

In this opinion-editorial piece, I write for political purposes and causes concerning the life of Zimbabwe in 2023.

Writing about Zimbabwe for political purposes concerning the year 2023 creates many dilemmas as the country is that part of the world where political disasters have been repeating themselves, true to Karl Marx, initially as tragedies, then as farces, and further as calamities that have come to define the polity and the economy of the troubled nation.

Looking at the history of Zimbabwe, recent and past, exposes the mind to a stew of political and economic catastrophes that require an entire career to make sense of and explain with some clarity.

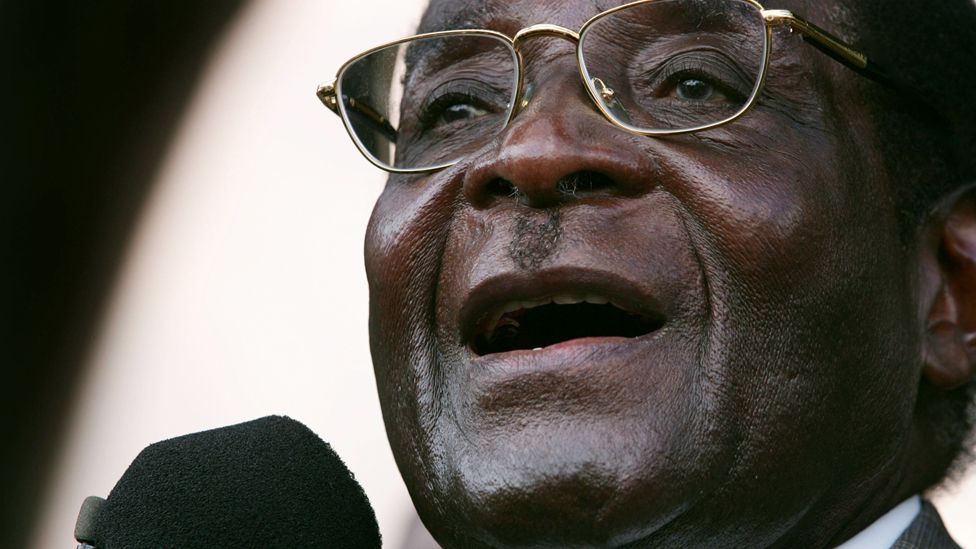

Tragic failure has become the most obedient metaphor at attempting to describe the Zimbabwean political and economic condition, starting with Ian Smith’s Rhodesia, Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe and Emmerson Mnangagwa’s “chinhu chedu”, where an entire country has been collapsed into “our thing” that the leader, his family, fronts and friends can toy with, and literally eat.

Smith, Mugabe and Mnangagwa dramatise Zimbabwe’s recent tragic lack of leadership.

How to Eat a Country and Get Away With It is a fitting title for a documentary that can expose how the storied “Second Republic” has outdone Smith and Mugabe in leading a few privileged beneficiaries of political patronage and cozenage in eating Zimbabwe away.

As the prefects of the political patronage monstrosity are getting paid, the dissenting voices such as Job Wiwa Sikhala are severely punished. The law, bail and pre-trial detention processes are manipulated for political agendas to crush dissent.

Underlying this failure of leadership and governance, violence has been a constant feature of Zimbabwe’s political landscape, and the prospect of violence hangs over the upcoming general elections.

The incidents of violence in Kwekwe, Gokwe, Insiza. Matobo and Murehwa – characterised by brutality and murder – show the spectre of bloodshed is looming.

Zimbabwe has been soaked in blood, from the colonial to the post-colonial times.

The country has been mismanaged and looted on an industrial scale, especially in the past 43 years of Zanu PF rule.

Instead of taking a step back and thinking deeply to embrace a paradigm shift and new trajectory, the glib official narrative is that there is nothing wrong in Zimbabwe except the sanctions on the country that the West must urgently remove for people to breathe again.

It is precisely that myopic denial which partly prevents Zimbabwe from correcting past mistakes and taking a new direction to the future. In other words, trying to solve problems at the same level of thinking as they were created, or doing the same thing over and over again, yet expecting different results – the definition of insanity, to paraphrase Albert Einstein.

In fact, the grand deception even goes on to claim the country is now recovering!

Meanwhile, South Africa next door is leading the Sadc region and the entire African Union comity of nations to believe and market the falsehood that it is Western sanctions that are the trouble in Zimbabwe.

That the South African political establishment in whose economy Zimbabwean problems have become a domestic issue believes the untruth that it is Western sanctions that are hurting the Zimbabwean economy and polity is in not the fault of Mnangagwa’s “Second Republic”, but that of the political opposition which has failed to mobilise the African continent to understand the genesis and context of the real problem of authoritarianism, corruption, and native colonialism in the country.

Among the many problems afflicting the opposition in Zimbabwe, one of them is that it is badly struggling in generating political ideas, policies, programmes, communication and messaging. The opposition needs to look itself in the mirror and start doing things differently – it has to champion new ideas, new politics and political culture and new methods of engagement, away from the Zanu PF modus operandi.

Given this, the crisis clearly consists precisely the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in the interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear, as Gramsci would say.

It is for that major reason that pondering the Zimbabwean polity and economy as a subject of political explication requires generous amounts of emotional stamina and Maoist wisdom.

Confronted with such catastrophes of an era in China, Chairman Mao Zedong remarked that “there is great disorder under heaven, the situation is excellent.”

What is excellent about such disorder as the Zimbabwean political and economic condition of tragic, farcical and disastrous extents is that it is still an opportunity for political thought and political activism, vita activa and vita contemplativa, as Hannah Arendt noted.

With positive political thought and courageous political activism, combined, Zimbabwe can be recovered from the present dystopia and restored to a better order, even if that order may not be an easy utopia.

It may be some post-political simplicity of some in the Zimbabwean political opposition and civil society that a paradisal Zimbabwe may be fashioned out of a miraculous electoral victory in 2023, as main opposition CCC leader Nelson Chamisa seemed to suggest in his New Year message.

It may even be political naivety to promise the unsuspecting Zimbabwean populace such a political miracle. There is need for Zimbabweans to invest in political thought and political activism for another Zimbabwe, a new Zimbabwe to be fashioned out of the present disorder and dystopia.

Talking of political thought and activism, Zimbabwe needs new ideas, renewed activism and fresh political agency that contribute to the emergence, re-energisation and articulation of how its political society – with specific attention to its institutions and governance – should be arranged; how agents ought to act and what steps could be taken to transform existent structures in the new direction.

At the moment, civil society and the opposition are mainly talking about how to replace Zanu PF, just like the ruling in many ways simply wanted to replace the colonial administration.

If one examines the opposition’s proposals and manifestos around politics and the economy, there is not much of a difference with Zanu PF. Even in terms of how they structurally organise themselves and approach issues, they largely mimic the Zanu PF model – sometimes unwittingly.

That needs to change, and change fast.

The Zimbabwean political and economic condition, if it is food for thought as I observe, then it is not fast food, but hard and slow food that requires true Maoist political commitment.

The tragedy has been that, both in the ruling cabal and the political opposition, where thought is found it is not accompanied by activism and where activism is found it is not always accompanied by thought.

The result of that paradox is that the Zimbabwean political theatre has mainly been a site for thoughtless action and actionless thought. What Zimbabwe is dying for right now is positive political thinkers and courageous political actors, both from the political opposition and the ruling outfit.

As political things stand, I observe, the ruling outfit cannot be reformed, but it needs to commit political suicide, and that needs courageous insiders that can action change out of the great disorder that offends the heavens. It is my political observation that courageous inside movers within the system working with thoughtful outside actors are the principal ingredient in the political brewery needed to stir the pot, catalyse events and secure change to save Zimbabwe.

This is what happened in Zambia, Malawi and Kenya. Zimbabwe needs to go that route to uproot Zanu PF. This must not be taken as an idle political idea, but a serious proposition that must be relentlessly pursued with courage and determination.

The dreams that one day an electorally victorious political opposition or a resilient and “revolutionary” ruling party will reform and deliver Zimbabwe from disorder are exactly that, post-political dreams that are bound to collapse into horrific nightmares.

In Hararian political parlance, they say “zviroto zviroto” (dreams are just dreams).

When the Saints Go Marching in is an old Christian hymn of the late 1800s that describes the victorious entrance of the holy Saints on the day of redemption. No one has yet written or performed the gallop of evil monsters invading the earth to eat their victims alive.

Political philosophers, scientists, and journalists have only tried to describe the arrival of evil political regimes.

In 1997, two Zimbabwean political scholars and courageous activists, Professors Masipula Sithole and John Makumbe observed in an essay that when Zanu PF came from the bush war in 1980 it came intoxicated with a “one-party state psychology.”

The men and women of Zanu PF that emerged from what was supposed to be a war of liberation were drunk with the political desire of Zanu PF rule without opposition under the life presidency of one Robert Mugabe.

One-party states and attendant politics were the zeitgeist at the time across Africa, and elsewhere.

As Margaret Monyani wrote: “A one-party system was a characteristic of many African states particularly immediately they gained independence and more rampant in the period between 1960s to the 1980s.

“Many scholars have attributed this to various factors, including the fact that democracy was considered as alien to Africa. For instance, apologists of the one-party regime such as Mwalimu Nyerere maintained that African traditional societies were akin to one-party system (Nyong’o, 1992).

“Others, like Kwame Nkrumah, maintained that democracy or multi-party regimes were divisive hence unfit for the newly independent African states which needed a unified energy and enthusiasm so as to move forward (Widner, 1992). Additionally, most of the leaders that transcended into power at that time did so through the huge support from locals who were mainly subsistence farmers. “Therefore, in order to have control over this electorate, socialism was favoured while capitalism was shunned. The expectation was, the post-independence governance structure would mirror the archetype of the colonial master’s home country.

“For instance, in the British colonies it was anticipated that those who lost will definitely form the opposition wing in parliament. This did not happen automatically as a number of African countries including Kenya, Ghana, Zambia, Mali, Senegal and Tanzania adopted the one-party system (Renske and Nijzink, 2013).

“In most cases, the dominant party of the day and the charismatic leaders who played the lead role in the fight against colonialism assumed the leadership of such parties.”

Mugabe was obsessed with the one-party state model. He was prepared to kill for it.

It is that burning and bloody desire that led to the Gukurahundi genocide where thousands of Zapu members and supporters in the Midlands and Matabaleland provinces were killed, some displaced and others dispossessed of whatever belongings they had. Some of the victims of the genocide are living as stateless and nation-less bodies in South Africa, Botswana and other countries up to this day.

What motivated Mugabe, overzealously assisted by the then State Security minister Emmerson Mnangagwa, Sydney Sekeramayi, Enos Nkala, Nathan Shamuyarira, Frederick Shava and others, to plan and commit massacres to clear the political landscape in Zimbabwe for a Zanu PF one-party state regime under the life presidency of Mugabe?

This dark and bloody goal was achieved in de facto terms in 1987 when Zapu leader Joshua Nkomo and his party capitulated and surrendered amid unprecedented and bloodshed and was swallowed by Zanu PF under the dubious Unity Accord agreement that institutionalised the one-party state project and marginalisation of some local communities, particularly those in Matabeleland.

The reason why the political opposition in Zimbabwe and civil society remain under attack from Zanu PF long after the neutralisation of Zapu is mainly that the ruling party, which in veracity is now a faction of Zanu PF, has never abandoned the “one-party state psychology” that it brought from the bushes of Mozambique to Harare.

At what point did Zanu PF say it no longer subscribes to the one-party state agenda? It never did.

Its leaders still believe in it and indeed in a life presidency. That is why you now hear Mnangagwa’s supporters starting some low-key familiar noise of him going for a third term after 2028.

That is how Zanu PF is wired. That is its DNA.

The men and women of Zanu PF that emerged from the bushes of Mozambique were not liberators that were ready to govern in a multi-party democratic system in post-independence Zimbabwe, no.

They left their families and went to the bush as patriotic liberators and came back as some monsters that were prepared to eat their families in Zimbabwe in the name of politics. These were monsters that were trained and indoctrinated to rule by a combination of force and fraud.

These were “comrades”, as they called themselves, that were ready to seek, find, and keep political power by any means necessary and unnecessary. A dark, bloody and unnecessary “will power” possessed Zanu PF comrades that committed killings and divided Zimbabwe ethnically to a thing almost beyond repair.

Yet it is not everyone in Zanu PF who believed in that. Political gladiators within Zanu PF like Eddison Zvobgo and others in the more enlightened wing of the party did not.

Zapu did not.

In the regional neighbourhood, Seretse Khama did not. Soon after winning elections in 1966 as Botswana gained independence from Britain, Khama said he would never seek a one-party state even though the ruling BDP has remained in power since then for different reasons.

The problem of Botswana politics is different from that of Zimbabwe. Even the way the countries are governed is vastly different. That is why Botswana has emerged from being a poor village in 1966 to a vibrant frontier economy now built by post-colonial leaders. Zimbabwe is the opposite.

It will take positive political thinkers, courageous political activists, from the ruling party, the political opposition, and civil society to address the national question in Zimbabwe, achieve national unity, reconciliation, justice and a united pursuit of some national futures.

It is another tragedy that the political opposition in Zimbabwe always promises to dethrone the ruling party and bring democracy and development to a Zimbabwe whose foundation, the national question and nation-building, has not been addressed.

In an informative paper, Discipline and Punishment in ZANLA: 1964–1979, Professor Gerald Mazarire (2011) describes the violent habits of political violence, torture, and murder that were practiced in the bushes of Mozambique. Young Zimbabweans who left their families to fight for the liberation of the country from Rhodesia were taught how to kill with impunity by a clique of particularly bloodthirsty and evil individuals.

Assassinations of comrades and foes were adopted as a military and political tool of choice. Political hate and ethnicity were cultivated and promoted as a kind of political religion that was to be held, believed faithfully, and used against those that were marked as outsiders to the tribe.

Burying Zipra commander Lookout Masuku in 1986, who died in detention at the hands of Mugabe and his political brutes over false political allegations linked to the aggressive push for a one-party state, Nkomo lamented that the “amount of hate in this country is frightening”, citing Zanu PF’s slogan of “pasi ne Zapu, pasi na Nkomo” (down with Zapu, down with Nkomo” as the daily spew of political bile and hatred from the new government.

These slogans such as “pasi ne mhandu” which means “down with the enemy” became singsong. Songs like “Zanu

ndeyeropa” which means “Zanu PF was founded with blood” were the hymns of the political cult that did not only hijack Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle, but actually colonised and captured it for other purposes that we have come to know only too well.

The nation-building project under Zanu PF has failed.

As Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni asks in one of his books, that is why there is still a stubborn question lingering which is ifZimbabweans as a nation that sings one anthem, salutes the same flag, and work for one national future exists.

Zimbabwe as a country might exist geographically, but Zimbabweans as an organised society, national polity and political entity are not yet born, thanks to the 1980 revolutionary abortion.

Zimbabwe was stillborn in 1980. That is why 43 years of trying to bring it to life have been a disastrous failure.

About the writer: Dr William Jethro Mpofu is a researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand’s Wits Centre for Critical Diversity Studies in South Africa. Mpofu is also a senior research associate at Good Governance Africa (GGA).

You may like