ZIMBABWE angrily withdrew from the Commonwealth in December 2003 after throwing a severe temper tantrum. In 2018, Harare applied for readmission, which explains why a Commonwealth delegation is visiting Zimbabwe to assess progress made by the country since the request to rejoin the club.

Through the Harare Declaration of 1991, Commonwealth member states committed to a set of core values, including democracy, the rule of law and human rights. The Zanu PF government’s failure to uphold those same values — that are also contained in Zimbabwe’s 2013 national constitution — has reduced the country into a tragic caricature of African failure.

The Commonwealth mission will see for itself how the democratic deficit continues hampering the country from moving forward — five years after Robert Mugabe’s dramatic ouster falsely heralded a transition to constitutional democracy.

Today, a few months before the 2023 polls, the pre-election environment is characterised by state-sponsored violence, the silencing of dissent and the victimisation of political prisoners. What is worse, management of the electoral process is not instilling public trust and confidence.

It will be remembered that in the aftermath of the 2018 general elections the Commonwealth Observer Group — making a return to Zimbabwe for the first time in 16 years — concluded that it was unable to endorse the polls as credible, inclusive and peaceful.

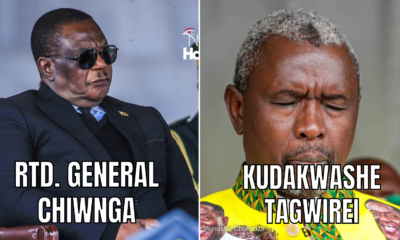

We are headed for yet another disputed election if Africa and the international community do not act decisively without further delay. To gain a better understanding of the Zimbabwean crisis, you must trace its genesis. This country has been a closed securocratic state for decades. Since 2017, it has become a fully fledged militarised state.

In neighbouring countries, the state possesses a military; in Zimbabwe, the military possesses a ruling party.

Professor Martin Rupiya has written about “the naked politicisation of the military amid the militarisation of Zimbabwean politics”.

Who can forget the shocking spectacle of 9 January 2002 when the top military generals appeared on state television and arbitrarily redefined the qualities that a politician must possess to qualify for the presidency.

At that time, Mugabe wrongly assumed that the men in uniform were on his side – and they indeed rescued him from the proverbial jaws of defeat at the hands of the opposition. But he was in for a rude awakening on 21 November 2017 when the military toppled him.

During a Sapes Policy Dialogue discussion on Thursday this week, Tony Reeler, a long-standing human rights activist and researcher, asked a pertinent question: Where is the church? Religious institutions wield moral authority and history has shown that they can play an important role in shaping the polity.

Every community in this country has a place of worship. Those religious centres can galvanise society in a desired direction. There is no doubt that if the church takes a united and non-partisan stand, puts its foot down and beseeches the government and citizens to shun violence, Zimbabwe would stamp out political violence and enhance the chances of convening a clean election. Contributing to the same public discussion, Roselyn Hanzi, the executive director of the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, raised a noteworthy point.

She said Zimbabwean society should be proactive in pushing back at ongoing attempts by the authorities to silence and control civil society.

The militarisation of politics is the reason why state institutions which ought to be non-partisan have been captured by political overlords. The rot runs deep. This week, the Zimbabwe Gender Commission embarked on consultations to gather views on challenges hindering women’s participation in the economy.

But if the commission were serious about its constitutional responsibilities, it would have taken action against political thuggery on women. When will the Chapter 12 institution do anything about the brutal assault on opposition MP Jasmine Toffa (pic) by Zanu PF thugs?

Toffa sustained broken limbs. Such barbaric attacks dissuade women from participating in politics. They entrench political hostility and impunity. As if to confirm a troubling pattern, the Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission and the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission have also not taken action against the perpetrators of that dastardly attack on Toffa in Insiza.

How can law-abiding citizens take such institutions seriously? Other MPs, notably Kucaca Phulu and Daniel Molokele, were also attacked by Zanu PF thugs in Matobo. Women activists were violently disrobed. The evidence is available, but state institutions have not taken action in line with their constitutional obligations. The writing is on the wall.

Unless Africa and the broader international community take decisive action now, Zimbabwe is headed for yet snother sham election. State-sponsored violence, partisan state institutions, the silencing of dissent, a shoddy electoral management system and blatantly biased state media are a recipe for disaster.