Opinion

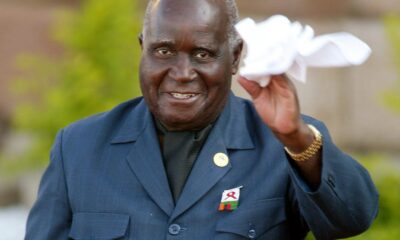

The African idea of Africa A tribute to Kenneth David Kaunda of Zambia

Published

5 years agoon

By

NewsHawksSABELO J NDLOVU-GATSHENI

Introduction: Is it an end of an era?

THE historian Paul Tiyambe Zeleza depicted the time of struggles for independence in Africa as the “proudest moment in African history” predicated on “nationalist humanism”. Kenneth David Kaunda was a leading proponent and indeed an advocate of the philosophy of liberation underpinned by African humanism. Nelson Mandela was another who drew inspiration from the spirit of ubuntu.

Julius Nyerere embraced it as African socialism founded on African familyhood (ujamaa). Leopold Sedar Senghor combined Negritude and Marxism to advance African socialism. Kwame Nkrumah explicated a synthetic philosophy of decolonisation and the remaking of a new African personality in terms of Consciencism, which involved tapping into the best values from African, Islamic and Euro-Christian traditions.

With the death of Kaunda at the age of 97 at a hospital in Zambia this week, Africa has lost the last standing giant of the first generation of African nationalist liberation fighters. This point was delivered forcefully in a tribute by the former president of Nigeria Olusegun Obasanjo. In his tribute, Obasanjo wrote: “The demise of President Kaunda at the grand age of 97 brings to an end the pioneers and forefathers who led the struggles for decolonisation of the African continent and received the instrument of independence”.

According to Obasanjo, Africa must gain solace from the fact and knowledge “that President Kaunda has gone to a well-deserved rest and to proudly take his place besides his brothers such as Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia, Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal, Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria, Ahmed Sekou Toure of Guinea, Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Cote d’Ivoire, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Nelson Mandela of South Africa, to name but a few.”

What is noticeable is that Obasanjo never mentioned any of Kaunda’s “sisters”, only “brothers”! This immediately raises an urgent issue not about the departed Kaunda but about how the African nationalist pantheon is dominated by men. Women are often ignored.

This issue arises poignantly because such a moment as this one where we have lost a “father” of the African nationalist revolution, our duty is not to mourn but to reflect of what they stood for and assess the trajectory of the African nationalist revolution to which Kaunda sacrificed so much. At the very centre of the African nationalist revolution has been the making of the very idea of Africa and redefinition of Africanness.

From the idea of Africa to the African idea of Africa

The cognitive empire operates through aggressive invasion of the mental universe of the world and subjects its targets to its own ways of knowing and imposes a particular memory. “Discovery” is its key trope. What is claimed to have been “discovered” is conquered, named and owned. With specific reference to Africa, The Congolese intellectual Valentin Y. Mudimbe in two celebrated works The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge (1988) and The Idea of Africa (1994) wrote about how Africa was invented from outside.

The active inventers being missionaries, colonial/imperialist ideologues and anthropologists and others. However, Wole Soyinka in his book Of Africa (2012) posited that unlike other continents which were claimed to be “discovered”, there is no one who claims to have discovered Africa as a continent. Soyinka goes on to argue that “This gives it [Africa] a self-constitutive identity, an unstated autochthony that is denied other continents and subcontinents.”

It would seem the existence of Africa was known. How can it be otherwise, since Africa is the cradle of humankind! Of course, Soyinka accepts that the colonial paradigm of difference did not spare Africa in the sense that the Europeans claimed to have “discovered” ancient ruins, sources of big rivers, mountain peaks, exotic kingdoms and sunken pyramids—but no one claimed to have “discovered” Africa itself.

The African idea of Africa as compared to Mudimbe’s idea of Africa speaks to Africa’s self-constitution and self-representation by Africans themselves. It was Ngugi wa Thiong’o in Re-membering Africa (2009) who challenged Mudimbe’s idea of Africa and laid down “the African idea, as African self-representation.”

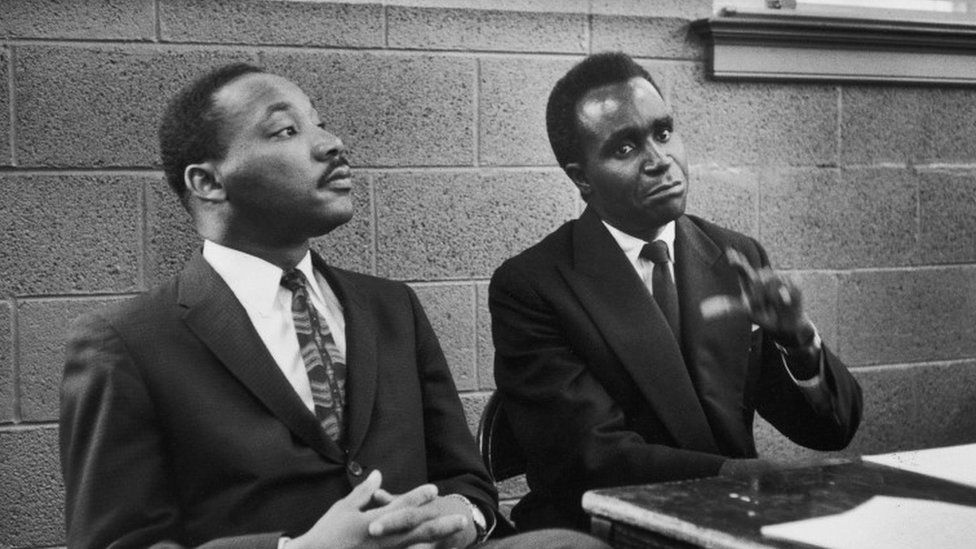

While Ngugi wa Thiong’o saw this idea as “forged in the diaspora and travelled back to Africa”, Ali A. Mazrui in his influential article “We Are all Africans” (1963) underscored how African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda actively contributed to the making of the African idea of Africa. This agenda materialised within a context where colonialists were propagating the idea of a “dark continent” inhabited by a people whose humanity they questioned, and denied that they had any history and any role to play in human history.

Such intellectual-cum-ideological formations as Garveyism, Negritude, African Personality, Pan-Africanism, African Socialism, African Humanism, Black Consciousness, Afrocentricity, African Renaissance, and many others, were all initiatives aimed at making Africa from a Black and African vantage point.

What is distinctive about them is that they emerged from the battlefields of history and human struggles for re-existence and re-membering after centuries of being denied existence and being subjected to colonial technologies of dismemberment and dehumanisation.

At their centre were the overarching agendas of self-definition, self-representation, self-writing and indeed re-humanisation. Inevitably, they were confronted with limitations and even contradictions. Formations and knowledges born of struggle are never perfect and finished products. Without this background, African nationalism and African national revolution will not be fully understood and Kaunda’s legacy will not be properly comprehended by the present generation.

African nationalism and the African national revolution

Colonialists denied that African people were organised into “nations” and had national consciousness. In fact, Africans did not exist in the colonial imaginary and colonial practices. They preferred to define Africans as “tribes” — more specifically inchoate and contending “tribes” always fighting against each other. The leading Ugandan intellectual Mahmood Mamdani in his works Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and The Legacy of Late Colonialism (1996) and Define and Rule: Native as Political Identity (2013) have provided us with details on the logics and operations of colonial governmentality as well as the colonial invention of political identities in Africa. His core thesis is this: “Unlike what is commonly thought, native does not designate a condition that is original and authentic. Rather, … the native is the creation of the colonial state: colonised, the native is pinned down, localised, thrown out of civilisation as an outcast, confined to custom, and then defined as its product.”

This thesis dovetails with Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Osborne Ranger (1983)’s widely cited notion of “invention of tradition”. This became a key aspect in how Europe ruled Africa and how it actively made sure national consciousness did not develop among Africans using what Edward Said termed the “law of division” and Mudimbe termed the “paradigm of difference”.

But what must not be forgotten is what Homi Bhabha in The Location of Culture (1994) posited about colonialism, that despite its overwhelming presence as a modern power structure, it was simultaneously riddled with contradictions, internal instabilities, tensions, and incompleteness.

For example, while it was preaching and implementing the discourse of “tribes”, it was also making a few openings for African people to undergo modern education. It was the African educated elite who actively opposed colonialism and spearheaded African nationalist revolutions, of course mobilising peasants and workers as foot soldiers. Kenneth Kaunda was part of this African educated elite.

Their task was not easy. They carried a heavy burden. African nationalism had to be created within a context in which colonialism was sustaining African divisions for its own purposes. This is why Kwame Nkrumah posited that he was not born in Africa, Africa was born inside him. This must form the deepest understanding of the concept of “father of the nation”. It means conceiving the idea and making it alive.

Kaunda and his generation of nationalists created African nationalism. Of course, colonialism through its racism was already provoking “black consciousness”. Enslavement had already contributed to “black consciousness” as a transcendental identity. African nationalists contributed to the paradigm shift from the “idea of Africa” emerging from Europe to the “African idea of Africa” emerging from Africa.

The making of African nationalism involved the painstaking process of mobilising colonised people who were deliberately divided by colonialism into rigid invented tribal cages into “nations” worthy of the right to self-determination and self-governance. Kaunda’s book Zambia Shall Be Free (1962) was part of a resource produced in the process of making nationalism.

Therefore, what was revolutionary about African nationalism was its reinvention of a people who were reduced to “subjects” and socially ordered into “tribes” to united “nationals” fired up to fight and sacrifice lives for liberation from colonialism.

However, the phenomenon known as “tribalism” always haunted the African nationalist revolution with some who claimed nationalism during the day continuing to be entrepreneurs and advocates of “tribalism” during the night. What complicated the African national revolution was that there was always the power question.

This meant that while prosecuting the struggle against colonialism, African nationalists also fought among themselves for power.

The African people themselves also did not discard their other narrow identities for the bigger national identities easily. This is why one found such nationalists as Samora Machel of Mozambique positing that “for the nation to live, the tribe must die”. The leftists inclined African nationalists who thought that ethnic consciousness was a false consciousness that has to be replaced by true consciousness, which is class consciousness.

This did not solve the problem. Karl Marx had said it that workers have no country, hence he urged them to unite across national borders for a proletarian revolution. This implied that “nation-states” were under the control of bourgeois and the states were used for the oppression of class enemies. Indeed, post-colonial states were abused to even eliminate those considered as ethnic enemies of those in charge of them. Nation-building had to be done within this problematic context.

Nation-building and post-colonial patriotism

Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere are given as examples of successful nation builders compared to others who never even invested in the nation-building projects. Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, a leading intellectual from the Democratic Republic of Congo, posited that at the time of the attainment of political liberation in Africa, African leaders had three options to pursue.

The first option was just to inherit what was left by the colonialists and continue from where they left. The second was to look back to the pre-colonial times and try to rebuild post-colonial Africa using values and ideas that were considered African. The third option was to be creative and invent something new for Africa. This is the radical position of Frantz Fanon on decolonisation as more than a counter-force to colonialism but a creative one for a better world.

While many took the first option of taking over what was left by the colonialists, including state institutions, this easy option was the most problematic in terms of advancement of the decolonisation agenda and fulfilling what Issa G. Shivji termed the “great expectations” of the masses.

The first challenge was that the colonial state was nothing but despotic political formation which was bifurcated and used colonial law as an unmediated force of violence and conquest. How can such a formation be of use to deliver promises of decolonisation? It is not surprising that many of those who chose this path interpreted taking over the colonial state as an “arrival” and an end in itself and began to immediately use its despotic institutions to terrorise the population and even to commit genocide and ethnic cleansing. This option created what Achille Mbembe (2001) termed the “postcolony” underpinned by what he depicted as “commandment”.

The second option was also problematic in the sense that the wheel of history could not be turned back. However, there was a way through which the nationalist invention of post-colonial Africa could still draw positive aspects from African pre-colonial history for their purposes.

Unfortunately, most of what was claimed to have been borrowed from pre-colonial Africa was mixed with what was left by colonialists to create what became known as imperial presidencies underpinned by one-party state regimes. However, Nyerere, Kaunda and Mandela drew from African culture and history to layout a post-colonial nationalist humanism as a departure from colonialism’s paradigm of difference and capitalism’s naturalization of exploitation of people by other people.

It was also Nyerere, Kaunda and Mandela who embraced the third option and tried to create something new. Kaunda antagonised over how to translate popular anti-colonial nationalism into post-colonial patriotism and pan-ethnic comradeship. The glue for this became his philosophy of African humanism. He never degenerated into tribalism. His well-known slogan became “One Zambia, One Nation.”

Like Nyerere, Kaunda and Mandela can be best depicted as “Mwalimu” (pedagogical nationalist teachers who spent energy inviting their people into the nation and preaching the gospel of national unity). But the greatest experiment in creating something new in post-colonial Africa was symbolised by Nyerere’s Arusha Declaration: Policy of Socialism and Self-Reliance (1967). Here one sees an attempt to implement a philosophy of life. Mandela was creative in imagining a “rainbow nation” as a new political community borne out of the vicious system of apartheid colonialism, in which erstwhile enemies reconciled and lived together.

That these initiatives did not succeed as expected does not render them useless. There were many forces organised against their success. Neo-colonialism was one such major enemy of African progress. Invention of new post-colonial formations of service to the African without an epistemic revolution could not always work because old knowledges and epistemologies of equilibrium are always subversive against is new.

Nationalist idealism, which often predicated these radical initiatives on assumed change of attitudes of the people, was inadequate to the task. The reality is that old attitudes take time to die. For Mandela, the attempt to create a new political society without addressing the justice provoked new formations that are threatening his legacy to the extent of calling him a sell-out.

Kenneth Kaunda and the praxis of the “we” consciousness

If there is any African leader who embodied what Cornel West (2014) depicted as the “Black prophetic fire” predicated on a very strong “we” consciousness, it was Kenneth David Kaunda. West defines the “Black prophetic fire” as local in content and international in character. Kaunda’s African humanism was just that. It is a philosophy aimed at lifting one’s voice against all forms of injustice, violence and war.

Even if Kaunda is gone to his ancestors, his voice of justice and peace remains. Kaunda practically lived what he believed in. How would one explain his welcoming of Zapu, Zanu, and ANC as liberation movements into his country without understanding Kaunda’s “we” consciousness?

West elaborated that a “we” consciousness is concerned with the needs of others and is driven by the willingness to “renounce petty pleasures and accept awesome burdens”. This is what Kaunda did for Africa in general and for southern Africa in particular. In Kaunda, we indeed have a very “worthy ancestor”, to borrow a term from the South African sociologist Xolela Mangcu.

The “we” consciousness is opposed to the “I” consciousness laid down by Rene Descartes in his “Cogito, ergo sum”. Together with Nyerere, Machel, Sir Seretse Khama of Botswana, and Eduardo Jose Dos Santos of Angola, Kaunda built the Frontline States formation as a liberation front and risked being attacked by apartheid South Africa. The Frontline States matured into the Southern African Development Community (Sadc). All this was possible because Kaunda embodied true ideas and living theories.

Conclusion: Rest in peace KK

Let me end by joining Obasanjo is saying that the departure of Kaunda must remind us of the vision that his generation had for Africa and let us not compromise the principles of decolonisation. Colonialism, as Walter D. Mignolo warned us, “is not over but all over”. It is a pity that the African leaders of today seem to be suffering terribly from lack of ideology.

Most of them, if not all of them, have succumbed and capitulated to neoliberal capitalism and their refrain is about inviting capitalists to Africa under the name of foreign direct investment. African resources are exposed to external plunder as the elites in charge of our states have turned them into what the historian Frederick Cooper termed “gate-keeper” states.

Rents collected at the gates line the pockets of the ruling elites and their clients. Leadership has been turned into technical managerialism bereft of any ideology. The consequence is that post-colonial states in Africa are simply turned into problematic mini-corporations manned by a rapacious elite, which facilitate the movement of global capital.

Inevitably, rule of capital is naturalised and, as Ngugi wa Thiong’o once put it, “theft is holy”. The idea of revolution has been replaced by the neoliberal idea of “transitions”. This is why Obasanjo said that when he visited Kaunda in 2015 and asked him whether the Africa of today represents what he fought for, he simply “broke down and wept”.

About the writer: Professor Sabelo J Ndlovu-Gatsheni is chair in Epistemologies of the Global South at the University of Bayreuth in Germany.

You may like