Economy

Reform is necessary before sanctions are removed—US ambassador

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksZIMBABWE has been under United States (US) sanctions since 2003 for violating the rule of law and human rights, among other issues. The European Union also slapped sanctions on Zimbabwe in 2002 although most of the measures have been relaxed. Western sanctions remain a contentious issue in Zimbabwe with the government insisting they are not only unjustified but meant to punish the country for the fast-track land redistribution programme. The government also insists sanctions are affecting ordinary persons and militating against economic recovery. On 25 October 2019, the government organised a march against the sanctions following a solidarity declaration by the Southern African Development Community. An anti-sanctions gala is planned for Sunday. The NewsHawks (NH) Managing Editor Dumisani Muleya and News Editor Owen Gagare spoke to US ambassador Brian Nichols (BN) about the gala, rationale for the sanctions and what Zimbabwe should do for the measures to be lifted, among other issues. Below are excerpts:

NH: We are almost a year now into the first anti-sanctions march and on Sunday we are expecting a protest gala. Ambassador, what is your perspective on the march and the anti-sanctions gala?

BN: Well, first of all, it’s very exciting to talk to you NewsHawks, a new outlet in journalism. It is incredibly important for every nation, and certainly in the United States, the rights of free speech and journalism are enshrined in our constitution.

So, last year’s anti-sanctions solidarity day events I think were very much designed to distract the people of Zimbabwe from the real causes of the problems in this country. And I think if the government of Zimbabwe puts the energy that they put into organising these types of events, and generating statements from other Sadc members, into pursuing the reform agenda, that the government of Zimbabwe campaigned upon and talked about three years ago, in November 2017, and then, in 2018, at the inauguration of His Excellency the President, they would have advanced further in that reform agenda. And then the conditions that the restrictive measures that the United States, the European Union, UK, Canada, Australia and others have imposed would be met. So, I think this is a really hollow exercise that does not serve the greater interests of the people of Zimbabwe.

NH: Given that you think it is a hollow exercise, do you think Zimbabweans are going to come out in large numbers to support the online event?

BN: …I’m not sure how many people will turn up online for this event. But I think the priority for Zimbabweans should be addressing the problems that this country faces, and the problems that this country faces are things like corruption, inefficiency, a lack of transparency in the judicial system, inability for companies to do business here in a way that’s easy for them. The lack of guarantees of rule of law if you are an investor and of course the overarching major issues for average people, things like inability to buy the food that they need to survive. The average Zimbabwean makes about RTGS 11 000 a month, yet the average basket of goods in this country is now approaching RTGS 17 000 a month. So that means that millions of people can afford to eat; more than a quarter of the population suffers from stunting. That’s a sign of severe malnutrition. And the teachers and health care workers are in labour actions because they don’t receive the remuneration that they think is necessary to feed themselves and their families. Millions, sorry, I meant to say billions of dollars are lost to corruption…So those are the issues that the people of Zimbabwe should be working on.

NH: We have seen in recent years, whenever the debate on sanctions arises, it tends to be very divisive. It gets emotional and sometimes very, very polarising among Zimbabweans, among diplomats and other people. And yet, at the same time, there doesn’t seem to be consensus amongst Zimbabweans on the impact of sanctions on the Zimbabwe economy and, indeed, on the narrative that the sanctions have caused economic problems. Why do you think there isn’t any consensus around that subject among Zimbabweans, since you have been here for a while?

BN: So yeah, I’ve been here almost two-and-a-half years now. And I’ll tell you what I hear from the Zimbabweans that I meet out and about in the streets or in meetings. I think there is a clear recognition among average Zimbabweans that the issues of sanctions is a false issue. It’s a false narrative. I think that there are a few people there, actually 83 people, under US sanctions, that’s all in a country of 15 million people or so. It’s 83 people and 37 entities. So that could be companies or institutions, but mostly those companies are linked to individuals already on the list. So, you know, the people who are listed under sanctions, well, certainly they talk about them a lot…But the average person doesn’t care. The average person is very much focused on how are they going to earn the money they need to survive on that day.

NH: They are different ways. And perspectives of looking at the sanctions, as we’ve seen during the debates, and in recent times, the Zimbabwe government has always argued that the sanctions were imposed on those individuals and entities, primarily because of land reform. In other words, the US and EU imposed sanctions because they were not happy with the land reform. But we have also seen another narrative, which basically comes from the EU, the US and other members of the international community supporting these measures that says the sanctions were imposed because of a human rights abuses, the breakdown of the rule of law, and other issues like electoral theft. How do we reconcile these positions? What is the truth here? What do you think is the reason behind these sanctions?

BN: I don’t know if we have time to go into an extended history lesson. But let’s look at Lancaster House. Let’s go back to 1979 at Lancaster House and, at that time, certainly the UK government and others supportive to the process, governments like the United States, European countries, were all very much in favour of land reform on the basis of willing seller willing buyer. And if you look at the timeline of the sanctions and restrictive measures, really that comes about after you’ve seen things like Gukurahundi, the theft of elections; it comes about when you see a number of senior opposition people jailed or killed, trade unionists the same. So really, there was a much broader issue of human rights and respect for democracy that was going on. Obviously, what the government of Zimbabwe refers to as the fast-track land reform process was a chaotic process, where laws and norms were not respected. And the beneficiaries of the land redistribution in the beginning were senior officials in the Mugabe government, not the average people. And even at that time, we were seeing a wholesale plundering of the government by former president (Robert) Mugabe and his cronies. Those are the things that raised concerns in the international community. And it was only—you will recall—when the war veteran started protesting against Mugabe and then he pursues fast track… And the chaos ensues around the land ownership issue. So, the idea that this was because we in the United States, or the European Union, or the UK, were opposed to the redistribution of land based on willing seller willing buyer, that’s a false narrative.

NH: But the issue of sanctions seems to be very nuanced. Can you explain the difference between the US executive order of 7 March 2003 and the Zidera?

BN: Under US law, the Emergency Economic Powers Act, the President of the United States has the ability to impose sanctions in a variety of ways and there are specific regimes that restrict the ability of US persons to do business with foreign entities, typically because those foreign entities or persons fail to respect human rights, the rule of law, democracy, or engage in gross corruption. There are some legislative and executive order regimes that are global in nature, and some are country specific. With regard to Zimbabwe, there has been an executive order covering Zimbabwe, as you say, from the early 2000s, which has been renewed annually by the presidents of the United States. So that prohibits US persons from engaging in economic transactions with people who are listed under the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control. And in Zimbabwe, the number of those people is 83. So, it’s a very small number of people compared to the size of the population of Zimbabwe. There’s also legislation in the United States which provides for travel restrictions on individuals. So those same 83 people, I think all have travel restrictions on them imposed by the US Department of State, which prevents them from receiving visas to go to the United States. That’s the travel restriction. And that is for either human rights violations or corruption. The Zidera legislation is a separate process, whereby the Congress of the United States passed and the President signed legislation, which instructs the representative of the United States in international financial institutions not to vote in favour of lending to Zimbabwe until certain conditions are met. And the conditions include things like democracy, free and fair elections, civilian governance of the country and resolution to the outstanding land reform question in Zimbabwe. Those are some of the things that are mentioned in the Zidera legislation.

NH: If sanctions were to be removed, Ambassador, what are the steps that Zimbabwe needs to take in order to ensure that sanctions are removed? What should the government of Zimbabwe do?

BN: It should fulfil the promises that the government has already made. And, as I’ve said several times, this is a government that campaign on a reform platform, they talked about democracy, respect for human rights, respect for free speech, opening up the media space. On August 1 2018, when you had the shootings in the streets after the election, you had the Motlanthe commission, appointed by the President, he said he would implement the recommendations of that commission. No one has been prosecuted for the shooting of unarmed civilians. And there’s been no clear accounting of any compensation paid to the families of those who died. Reform processes within the security forces that the Motlanthe commission called for, there’s been no accounting as to what has taken place or what has not taken place, in a clear way that the people of Zimbabwe could objectively judge that. The issue of corruption in this country is a serious one. Look, in just this year, I don’t have to go back very far, in the Ministry of Health and Child Care, you have the minister accused of over US$60 million attempted graft. You have the Deputy Minister accused of a separate US$5.6 million scandal. There are multiple scandals in multiple hospitals and clinics for misappropriation of resources. And that’s just one recent example. If you go back to last year, at this time, and we were talking about the command agriculture programme, and the billions of dollars of graft associated with command agriculture, as documented by the Auditor-General, to the Public Accounts Committee. So, the resolution of those types of outstanding questions would obviate the need for restrictive measures by the international community.

NH: In terms of Zidera as originally enacted in 2001 and amended in 2018, the US is restricted from voting in support of new monetary assistance to Zimbabwe from international financial institutions. Is that not hurting the Zimbabwean economy and therefore the ordinary person?

BN: I think if you look at what’s happening, as reported in the inaugural issue of your fine newspaper, one of the issues that you talked about was the increase in debt that Zimbabwe has taken on in the last year. Is that not correct? So clearly, Zimbabwe is able to obtain lending. Now, I suppose there’s an argument that that lending could be on more favourable terms, if it were from international financial institutions. But let’s look at the facts. The IMF came here with a staff monitoring programme, that ended because the reform, the economic reforms, the IMF was calling for have not been fully implemented. And one of the key issues that they’re looking for is greater transparency in fiscal and monetary affairs, and continued rationalisation of public sector operations. I think as a practical matter, Zimbabwe is taking on more and more debt, regardless. You look at the Afreximbank lending to Zimbabwe, as one key area, you look at lending by other governments and institutions, often security against extractive resources from the Zimbabwe minerals, gold, in particular and diamonds. So, you know, I think the evidence really isn’t there, that this is the cause of any of the privations of the average person in Zimbabwe.

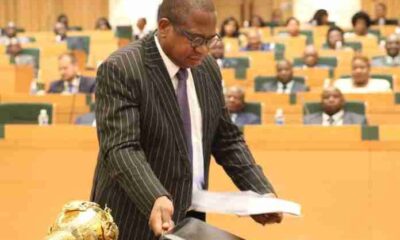

Hopewell Chin’ono

NH: Zidera lists some steps which Zimbabwe must take, for the sanctions to be lifted. How are we doing on that front? In other words, has it so far done enough to fulfil some of those demands that are in Zidera so that the process of lifting sanctions against it can start?

BN: No, I think Zimbabwe still has quite a way to go and among the areas that would be of concern, you had the government of Zimbabwe saying that by-elections are cancelled. So free and fair elections are a criterion for lifting of Zidera. You have the respect for human rights and the rule of law. And you have dozens of activists and opposition figures who have reported abductions, and questionable, if not outright illegal, arrest. The MDC three, the situation with Joana Mamombe, Peter Magombeyi, Hopewell Chin’ono, Jacob Ngarivhume, there’s just a long list of people who have had their individual rights abused, student leaders, trade unionists. So that lack of respect for human rights is a major concern in Zidera. Has Itai Dzamara’s disappearance been clarified? You know, so those conditions are far from being met. The preparations for the next election, it’s unclear how Zec is proceeding in those preparations. So that whole democracy space is very much in question. And then you look at what’s going on in the parliament, where the elected MDC members in Parliament have been removed in the wake of an extremely questionable court case. And someone who got less than 1% of the vote has taken over the opposition party, replaced its members in Parliament practically and said she’s in charge of the opposition; and is frankly allied herself with the ruling party. That does not speak well of democracy of Zimbabwe. And then another area is the issue of resolution of compensation questions around land. And the government has made an important step forward in the global compensation deed. However, we just saw the governor of Manicaland Ellen Gwaradzimba, who was talking about the questions around whether or not she’d allowed her son to legally seize a farm. And there are still issues of farm invasions that are being alleged right now. And the US$3,5 billion in compensation that has been agreed upon the global compensation deed agreement, it’s not clear how that’s going to be funded. So there’s a lot more work to be done in that area. I think that there are a lot of very positive possibilities for funding than, I think, creating a land bank. In Zimbabwe, greater use of 99-year leases and making land bankable could raise a great deal of money that would allow the compensation for improvements on the land to take place. So, you know, there are things that are positive, but they need to proceed.

NH: Ambassador, you just raised the issue of compensation for improvements on land that was taken by the government from white former commercial farmers. Would the United States consider contributing to that, if Zimbabwe were to approach it?

BN: What we said at the time of Lancaster House was that we would contribute to a resolution of these issues in Southern Africa as part of a broad-based effort, and that we would provide economic support to that broad-based effort, that’s more or less what we said in 1979 during the Carter administration. The United States since independence of Zimbabwe in 1980, has provided U$3.2 billion in assistance to Zimbabwe, a country of 15 million people. So last year, we provided over US$370 million in assistance to the people of Zimbabwe…Our support, about US$1.2 billion of that support has been focused in the area of health and another key area has been food security. And last year, we provided about US$110 million in assistance just around food security issues. And in 2020, I expect that our assistance will be roughly around the same amount. We’ve already contributed over US$62 million for rural food assistance through WFP (World Food Programme). And we’re providing another US$10 million for urban food assistance through WFP. We have long-term programming around the areas of making farmers more efficient and more able to earn a strong livelihood, those are five-year programmes that are averaging around US$15 million a year. So, there’s a great deal of support that the United States provides. Obviously, with Covid-19, we’ve provided over U$19.3 million in assistance for Covid-19 response in Zimbabwe. We have a large health team in our embassy, both from the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and from the US Agency for International Development that provides on- the-ground technical assistance and training to help the Covid-19 response, leveraging the assets that we’ve had here for a long time, as well.

NH: Still talking about the relations between the United States, we have noticed that you have been engaging the Zimbabwe government, particularly the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the US, Assistant Secretary for African Affairs Tibor Nagy, has also been engaging Zimbabwean government officials. Of late, we learnt that he spoke to the Foreign Minister, Sibusiso Moyo. How are the re-engagement discussions going? And then, secondly, as part of the same question, we also hear that Nagy asked Zimbabwe to be involved in Mozambique in relation to the militants in Cabo Delgado. May you just to shed some light on that?

BN: I think it’s very important that we maintain a respectful, open fluid dialogue between the government of Zimbabwe and the United States and I know that my diplomatic colleagues from other embassies present here share that view. And I very much want to maintain that regular dialogue with the government. I think it’s very important for us to share our views. And in the conversations that I’ve had, with the honourable Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, I have talked about the importance of implementing fully the reform agenda this government campaigned on and that is a prerequisite for overcoming the issue of sanctions. And the conversation that Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Ambassador Tibor Nagy and I had was very much along those same lines. We talked about our desire to have a closer and friendlier relationship, but that is dependent on the government of Zimbabwe implementing the reforms that it has said it intends to do. Certainly, the President’s statement in November 2017, at the time of the transition here, his inaugural, he talked about those things. In his campaign, they talked about those continuing. The billboards are still up in some parts of the country, talking about those commitments. And if Zimbabwe wants to achieve middle-income status by 2030, those are the types of reforms that will be required.

With regard to regional issues, Zimbabwe has been a part of the Sadc troika. And in that context, we have inquired what Zimbabwe and the Sadc troika’s view of the regional situation is, including the situation in Mozambique. We’re not advocating for any particular course of action. We really are just trying to share views as to what the situation in Southern Africa is. There are a number of issues, economic development, food security, national security and counterterrorism issues that are natural to discuss. Basically, if you look at the conversations that go on every year around the UN General Assembly, and that was the context of Secretary Nagy’s conversation. You know, those are the kinds of conversations you have with any nation that you are talking to…Those are normal conversations. But we are absolutely not advocating or calling on Zimbabwe to pursue any—or Sadc for that matter—to pursue any course of action, other than collectively pursuing the kinds of reforms and policies that will improve the lives of people of this region.

You may like