News

Mnangagwa tramples on constitution over Malaba

Published

5 years agoon

By

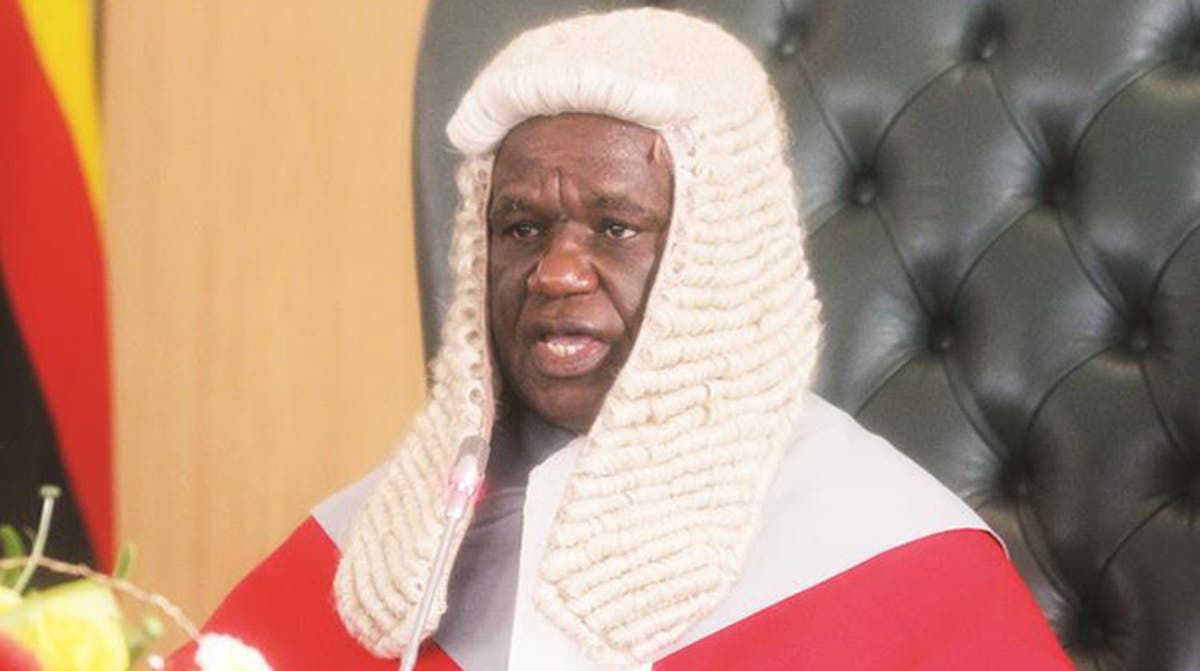

NewsHawksCHIEF Justice Luke Malaba is back on track after a temporary derailment of a controversial extension of his tenure linked to President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s 2023 re-election bid.

OWEN GAGARE/BERNARD MPOFU

This comes after high-stakes official interventions and railroading of the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Bill in parliament on Tuesday under a cloud of illegalities that may boomerang

on the movers of the deeply flawed process.

Malaba, by operation of law, ceases to be chief justice at midnight on 15 May.

“On his 70th birthday, at midnight on 15 May, Malaba will cease to be Chief Justice of Zimbabwe, but I can tell you that his bid for extension is strongly back on track and, barring any unforeseen eventualities, he will stay on, courtesy of Mnangagwa,” a top official in the Office of the President and Cabinet said.

“That’s the plan; he is staying beyond his 70th birthday.” In terms of the constitution, Malaba should retire at 70.

But top-level sources told The NewsHawks that he is now set for a controversial extension, which he desperately needs. Malaba was sworn in as chief justice on 6 April 2017.

This comes amid new details that Mnangagwa and Malaba are working closely on the political project which has serious democratic and constitutional implications. Their plot brazenly undermines the

constitution, constitutionalism, certain laws and rule of law principles, as well as shredding the tenets of good governance and accountability.

Mnangagwa wants Malaba to stay on for his 2023 re-election agenda which is being challenged both internally by Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga’s Zanu PF faction and externally by his main opposition rival, MDC Alliance leader Nelson Chamisa.

The endgame: Malaba may be decisively needed at Constitutional Court (ConCourt) and Electoral Court levels to rescue Mnangagwa and Zanu PF candidates respectively as many believe he did during the controversial 2018 elections when Chamisa petitioned the ConCourt challenging the President’s wafer-thin victory margin.

Malaba and his colleagues unanimously declared Mnangagwa the winner, amid grumbles that judges were suborned and whipped into line. During his five-year reign, Malaba steered important judicial reforms, yet he also browbeat the judiciary to be compliant – what ordinary people now call judicial capture.

He ran a tight ship and closely controlled the court system from top to bottom in aid of Mnangagwa’s authoritarian rule.

Having overcome the senate hurdle on 6 April, if Malaba is to secure an extension, two important things must now happen: Constitutional Amendment (No.1) Bill must be signed into law by Mnangagwa and Constitutional Amendment (No.2) Bill must also be passed and assented to by the President before 15 May.

At least for now, Constitutional Amendment (No.1) Bill has sailed through senate by 70 votes to one.

This after it did so through an irregularity on 1 August 2017 before it was nullified by the ConCourt on 31 March 2020. This is the process which culminated in its restoration on Tuesday.

Constitutional Amendment (No.1) Bill, among other things, seeks to allow the President to appoint the Chief Justice, Deputy Chief Justice and Judge President without subjecting them to the open selection process and public interviews.

This will allow Mnangagwa to retain Malaba at the helm of the judiciary. After that, Malaba will serve at the whim and caprices of Mnangagwa – meaning the judiciary will further be captured for five years

through renewable annual extensions.

Constitutional Amendment (No.2) Bill is needed to allow him to serve when he is over 70.

Pitfalls ahead

Even if he leaps over these hurdles, there is still section 328 which provides that “an amendment to a term-limit provision, the effect of which is to extend the length of time that a person may hold or occupy any public office, does not apply to any person who held or occupied that office, or an equivalent office, at any time before the amendment”.

A “term-limit provision” is defined as ‘a provision of this constitution which limits the length of time that a person may hold or occupy a public office’.

The provisions which set the maximum age limit of judges restrict the length of time that a person may hold or occupy office as a judge, which is a public office.

So section 328 remains a stumbling block.

However, senior government officials say Mnangagwa and Malaba have a plan around the problem.

“When the time comes, they will argue that the section does not apply to the chief justice whose tenure is limited by age, not by the number of years of service as section 328 says or implies,” a top source

said.

“But their rivals will say they are missing the underlying principle behind that; it’s not about age or years of service, but the principle that an incumbent cannot initiate, cause or influence an amendment of the law to benefit himself, especially retrospectively, hence their argument is flawed. It’s going to be a big legal battle; it’s not over yet.”

Although Malaba seems to be back on track, constitutional and legal impediments lie ahead. As part of securing an extension, he needs Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Bill to be signed into law by Mnangagwa.

This should be easy. In fact, sources say it will be signed and gazetted within the next week or so. Constitutional Amendment (No.2) should also be easier, it is likely to come within a week or two.

“The ministry of Justice is under instruction to railroad the process; as they did with Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Bill on 6 April and will do with Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 2) Bill within a fortnight,” another source said.

However, section 328 remains a barrier. Besides, there are other deep pitfalls in the path of the complex process.

First, the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.1) Bill straddled two different lives of parliament, the eighth parliament which ran from 2013 to midnight on Sunday 29 July 2018, and the currently running ninth parliament.

The tenure of the current parliament ends in 2023. In terms of section 147 of the constitution, this is unconstitutional and thus illegal.

Section 147 of the constitution reads: “On the dissolution of parliament, all proceedings pending at the time are terminated, and every Bill, motion, petition and other business lapses.”

When the ConCourt ruled on 31 March 2020 on the applications by Jessie Majome and Innocent Gonese that the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Bill was unconstitutional as it had been passed without the two-thirds majority as required by section 328 (5), this meant the Bill was null and void.

In any case, it had ended with the life of the previous parliament and cannot be carried over into the next parliament in terms of Section 147.

When parliament is dissolved, all unfinished business is liquidated. If the executive wants to push through a Bill from the previous parliament, it has to start afresh in the new parliament.

However, with Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Bill, the executive picked up from where it had left in the life of the eighth parliament, which is unlawful.

This followed a directive to senate by the ConCourt to go back and redo the Bill voting process. Lawyers are challenging that as unconstitutional.

They say the court was only required to rule on the constitutionality of the passing of Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Bill without a two-thirds majority, which it did, but then went ahead to direct a restoration of a Bill that legally was invalid and thus non-existent.

Whereas the ConCourt on 31 March 2020 directed that the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) Bill must be restored – giving senate 180 days to do – this issue has now become a moot point in court as shown by the 25 February ConCourt judgment in which Justices Rita Makarau, Anne-Marie Gowora and Bharat Patel clashed over whether or not they should grant a further 90 days to restore the Bill.

In a split judgment, Makarau and Patel granted the second 90-day extension, but Gowora dissented and wrote a devastating ruling crushing the senate process to restore the Bill in violation of section 147 of the constitution and with disregard to section 2 of the constitution that speaks to the constitution as the supreme law of the land.

Initial process

After the current constitution was adopted through a referendum in 2013, three years down the line the late former president Robert Mugabe’s government introduced Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) – H.B.1-2017. The Bill was gazetted on 3 January 2017. That nullified general notice 434 of 2016, which was published in the extraordinary gazette on 23 December 2016.

It was then introduced to the House of Assembly later in 2017 and passed on 25 July 2017.

Senate then passed it on 1 August 2017, but failed to garner the required two-thirds majority in terms of section 328 (5). On the day, 53 senators out of the total membership of 80 voted. That was one vote short of two-thirds.

However, senate fraudulently claimed it had met the two-thirds majority threshold since one seat was vacant and the Upper House then had 79 members, which equalled two thirds. But the law required at least 54 votes to pass the Bill, not 53.

As a result, legislators Majome, now a Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission commissioner, and Gonese challenged the process at the ConCourt, arguing the Bill should have been passed after a two-thirds affirmative vote by members of each House, in line with section 328 (5) of the constitution.

The ConCourt heard the consolidated case on 31 January 2018, but only passed judgment on 31 March 2020.

In the judgement written by Malaba, the court concurred that a two-thirds majority was not met in senate, while dismissing the allegation that a two-thirds majority was not secured in the National Assembly.

Former MP and minister Jonathan Moyo, who has closely followed the process, says the issue is riddled with unconstitutional irregularities and illegalities.

“Let’s summarise the processes and related cases first. Sometime in 2016, Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 1) – H.B. 1-2017 was introduced. The Bill was gazetted on 3 January 2017. That nullified general notice 434 of 2016, which was published in the extraordinary gazette on 23 December 2016.

“After that, the legislative process started until the Bill was adopted by the Lower House on 25 July 2017 and then by senate on 1 August 2017, but without the constitutionally required two-thirds majority in terms of Section 328 (5) of the constitution,” Moyo, also a professor of politics, said.

“Then the Bill was assented to by Mugabe and gazetted as an Act on 7 September 2017. However, it then got challenged by Majome and Gonese separately. The cases were then consolidated and heard in January 2018, but judgment only came on 31 March 2020.

“The problem then gets worse from there. The ConCourt nullifies the Bill because it had not met requirements of section 328 (5) of the constitution which requires a two thirds majority for it to pass.”

Three issues arise out of that, as already alluded to violation of section 328 (5). And then there was violation of section 147 of the constitution. This, read with Section 2 of the constitution which speaks to the constitution as the supreme law of the land, becomes clear that the Bill is null and void, and can’t be restored. The only legal thing to do to restore it would have been to restart the process in the new parliament.

But because the ConCourt had given a directive that senate should go back and restore the Bill, the process continues from the previous parliament even if the Bill was null and avoid — meaning it was no non-existent – and in any case in violation of section 147.

Furthermore, the applicants had not asked for a restoration of the Bill. They only wanted it declared invalid, which was done. So why did the ConCourt go further to issue a directive for the Bill’s restoration?

“Remembering that it was a full ConCourt bench, although the judgment was written by Malaba, we are left with no choice but to conclude the obvious: Malaba needed the Bill to be restored to allow Mnangagwa to appoint the chief justice, deputy chief justice and judge president so that he could get an extension that he requires.

“So he was acting out of self-interest. He did not declare that, hence conflict of interest. That renders the process fraudulent and corrupt. This is not an exaggeration. Corrupt because the objective purpose of Malaba issuing a directive to senate to restore the Bill, which was already invalid anyway, was to enable himself to be given an extension to stay on his job. Without restoration of the Bill, Malaba would not get an extension. So this ultimately means the process was blatantly fraudulent

and brazenly corrupt.

“The role of the judiciary is to interpret the law, parliament makes laws and the executive initiates them, and they also implement. The judiciary cannot be seen to be issuing directives to other arms of the state, just as the executive or parliament should issue directives to the judiciary. That is how checks and balances work.

“So what we have now here is a Malaba Amendment; a whole constitution being amended to assist Malaba to stay in office in order to help Mnangagwa to manage, manipulate and steal the 2023 elections. Now is it not fair to conclude that the process, its underlying intentions and hidden motives are political and corrupt? What we are seeing here is deceitful and corrupt political manoeuvring and corrupt electoral politics at play.”

Moyo said the ConCourt’s directive to senate to restore the Bill was problematic. The court gave senate 180 days to do so. When this was about to lapse on 28 September 2020, senate on 25 September 2020 lodged two applications at the ConCourt, one seeking a further extension of the 180-day period and an urgent ex parte chamber application for a provisional order extending the 180-day period, while also suspending the coming into effect of the court’s declaration of invalidity of the Bill.

The ex parte, which is an application without notice to other interested parties, was granted on 28 September 2020.

Parliament cited the Covid19-induced lockdown as a reason for failure to comply with the court order, although, for a long period, parliament continued meeting despite the lockdown. Parliament later introduced online sessions.

ConCourt lifeline

Moyo insists Malaba had a vested interest in issuing a directive to senate to restore the Bill. As noted by Veritas, an organisation with an interest in legal, constitutional and parliamentary affairs: “The Chief Justice and his colleagues, however, did not just make a simple declaration that the Bill had not been validly passed by parliament – which would have meant that the resulting Act and anything done under it were also invalid. Instead, it saw fit to suspend its declaration of invalidity for 180 days to allow the senate to conduct another Third Reading vote on the Bill and added that if by the expiry of the 180th day, the Bill had not been passed by 54 affirmative votes, the declaration of invalidity would come into force.”

ConCourt judgment

A three-judge ConCourt sitting comprising of Makarau, Patel and Gowora heard the substantive application on 10 November 2020 before granting another extension in a judgement delivered on 25 February 2021, offering a much-needed lifeline to Malaba in the process.

This led to the 6 April passing of the unconstitutionally restored Bill. In a split judgment, Makarau and Patel offered senate a new 90-day lifeline. Gowora vehemently differed in a devastating dissenting judgment.

Makarau said: “In view of the delay that has already ensued in deciding the fate of Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 1 of 2017, it is not desirable that the uncertainty in the supreme law remains for much longer. A period of ninety days will be sufficient to enable the second applicant to put its house in order regarding the proper constitutional procedures to adopt in the circumstances of this matter. Accordingly, I make the following order: The application is granted.”

However, Gowora came in guns blazing and she was devastating – demolishing the whole Makarau and Patel arguments, and the Bill restoration process itself. She basically buried the whole Constitutional Amendment (No.1) process.

“On the dissolution of parliament, all proceedings pending at the time are terminated, and every Bill, motion, petition and other business lapses. As a result of the declaration of invalidity by this Court, Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 1 never became law. By parity of reasoning it would then revert to a bill pending before the senate for the conduct of a proper vote as directed by this court. It was inevitably affected by the dissolution of parliament in that it automatically lapsed,” Gowora said.

“I am not dwelling on when the order was granted. It was invalid by process of law from not having been passed in accordance with the constitution. Thus, there is no bill to debate and vote on. The senate would have to commence the process afresh following the setting aside of the proceedings by which the invalid votes were garnered.

“Section 147 must be given effect to. There is no bill left to debate. Any attempt by the senate to debate and vote a bill that has lapsed by operation of law is in violation of the constitution itself. The constitution protects itself. Section 2 tells us so in clear and unequivocal terms. It provides:

“Supremacy of constitution: This constitution is the supreme law of Zimbabwe and any law, practice, custom or conduct inconsistent with it is invalid to the extent of the inconsistency.

“The obligations imposed by this constitution are binding on every person, natural or juristic, including the state and all executive, legislative and judicial institutions and agencies of government at every level, and must be fulfilled by them.”

So in essence, Gowora says Constitutional Amendment (No.1) is null and avoid as there was no Bill for senate to restore and pass on 6 April 2021.

If Mnangagwa goes ahead it to assent to it, he would almost certainly be approving of an unconstitutional Bill or a non-existent Bill. Patel said he agreed with both judges, although he crucially sided with Makarau to give senate a new lifeline, hence momentum to Malaba and Mnangagwa’s 2023 plan.

“I cannot but agree with Gowora AJCC that the supremacy of the constitution, as enshrined in section 2 of the constitution, dictates that any law, practice, custom or conduct that is inconsistent with the supreme law is invalid to the extent of the inconsistency. The ineluctable consequence of this principle is that anything done by parliament that is contrary to the provisions of the constitution, including section 147, would be invalid and unconstitutional to the extent of such inconsistency,” Patel said.

“Nonetheless, in the particular circumstances of this matter, despite the clear substantive implications of section 2 of the constitution, I am inclined to concur with the predominantly procedural stance adopted by Makarau AJCC in the determination of this application.”

New hurdle

Given all the hurdles above, especially violation of section 328 (5) and section 147 of constitution, and the import of section 2 which speaks to the supremacy of the constitution – and, above all, the ConCourt’s 31 March 2020 judgment that the Bill was null and void, but still gave a

directive to senate to restore it – and Gowora’s dissenting ruling that it remains a nullity and cannot be revived – Malaba is running into a cul de sac, although Mnangagwa will railroad and bulldoze through the process to give him an extension on 15 May, raising a big constitutional question and potentially explosive new court battle ahead.

You may like