News

LONG READ | ‘We’ll get him dead or alive’: Reid’s Mpiranya trail to Zim

Published

2 years agoon

By

NewsHawksA BESPECTACLED white man of medium height probably in his early 60s walks into the hotel restaurant where I am seated outside on patio couches basking in the sunshine while surfing social media platforms.

DUMISANI MULEYA

He is accompanied by a lanky dark black lad in his early 30s with thick afro hair which seems a product of natural growth rather than locks styled with curling chemicals.

The black guy looks around, dials his phone and my iPhone immediately rings. So these are the guys, I think to myself.

‘We’ll get him dead or alive’: Reid’s Mpiranya trail to Zim

I pick the call and tell them I was sitting outside; I had seen them walking in. After a brief call, I go into the restaurant teeming with guests who have just finished their late breakfast to join them.

I had arrived early for the meeting despite that the previous night — 11 March 2020 — I had slept late at some nondescript hotel after watching holders Liverpool going down 2-3 to Atlético Madrid (2-4 on aggregate) in the Uefa Champions League Round of 16, second leg at Anfield through a Marcos Llorente double and an Alvaro Morata goal.

Liverpool had scored through Wijnaldum and Firmino. I was particularly electrified by the match as boys from the team I support with my life — Real Madrid, Llorente and Morata, had done the damage. Llorente had dramatically struck twice in extra time — the sort of shock therapy Real Madrid gave to Manchester City recently in the Champions’ League semis — as Atlético stunned the seemingly invincible Liverpool at home. After sensationally eliminating City, Madrid take on Liverpool on 28 May next weekend in the final.

They beat them 3-1 in the final in 2018 in Kiev, now a theatre of war, not theatre of dreams. Back to the hotel, we exchange greetings and niceties before settling down on chairs for formal introductions.

The white guy looks relaxed, cordial and welcoming, while the black bloke appears genuinely happy to see me. I was comfortable, but did not know what to expect in the touch-and-go meeting which had interdependent and mutually reinforcing objectives: To investigate the whereabouts of Rwandan genocidaire and fugitive Protais Mpiranya, and hold him to account for crimes against humanity. The two guys wanted Mpiranya for international crimes accountability, while we wanted a story.

The aura of uncertainty surrounding the meeting was exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic’s looming shadow of death hanging over the world, including Africa, with indecipherable repercussions at the time.

Kenya, like many other countries including Zimbabwe, had not yet imposed a Covid-19 lockdown. Lockdowns and curfews came soon after that.

The two men who had come to meet me at the hotel in the affluent Westlands area in the Kenyan capital Nairobi opposite Westgate Mall, the scene of Al-Shabaab-perpetrated terrorist massacres in which 71 people were killed in 2013, were Robert “Bob” Reid, an Australian detective who gained global fame as probably the best investigator in the world during his days as operations chief for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia after tracking down more than 160 Balkan war criminals, including the world’s most wanted fugitive then, Ratko Mladic, and a young Zimbabwean lawyer Jasper Gwasira working with him at the United Nations International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT).

As a result of the Westgate Mall terrorist attacks, security checks at Kenyan hotels, malls and other public places is unusually tight. Reid had a well-earned reputation for tracking down lawbreakers, criminals and genocidaires, and nailing them even when the trail falters for years from a long career which started in small policing localities in Australia before he entered the global stage.

His hunt for and capture of Mladic, the “Butcher of Bosnia”, responsible for the murder of more than 7 000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica in 1995, remains the stuff of legend. Mladic had been running for 16 years when Reid tracked him to a derelict farmhouse in northern Serbia.

Reid and his investigators caught up with him to face the tribunal, which convicted him of genocide and crimes against humanity in 2017.

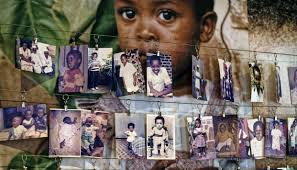

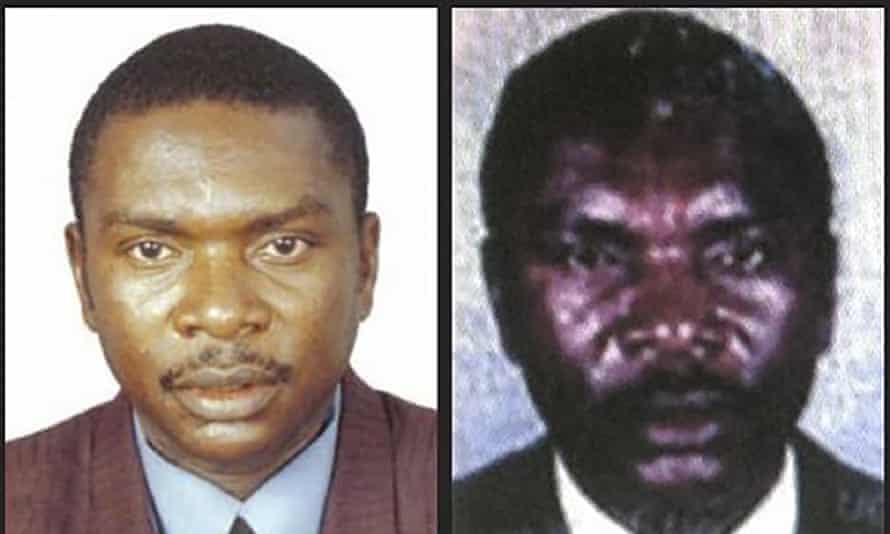

He was sentenced to life in prison. After spearheading the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, as commander of the Presidential Guard under the assassinated president Juvenal Habyarimana, Mpiranya was indicted by the International Criminal Court for Rwanda (ICTR) in 2000, made public in 2002.

He was charged with eight counts of genocide, complicity in genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Notably, he was charged with responsibility for the murders of senior moderate Rwandan leaders at the start of the genocide, including prime minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, president of the Constitutional Court, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Information.

He was also charged with the murders of 10 Belgian United Nations peacekeepers during that same period in which 800 000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were massacred within 100 days in one of the world’s darkest modern periods spoken in the same wave length as genocides in Darfur, the Balkans, Cambodian killing fields, Armenia, Namibia and the Nazi-led Holocaust, among others.

The IRMCT was established by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1966 (2010) to complete the remaining work of the ICTR and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia after the completion of their respective mandates.

The mechanism has two branches, one in Arusha, Tanzania, and one in The Hague, Netherlands. So Reid, whom colleagues just call Bob, and Gwasira had travelled from Arusha to Nairobi for the meeting. I had travelled from Harare to Johannesburg en route Nairobi.

We were looking for Mpiranya for related, yet different reasons. They wanted him arraigned to face justice for genocide and crimes against humanity, while we wanted a story about his whereabouts as one of the world’s most wanted killers.

As we were preparing to set up our investigative journalism project The NewsHawks, we wanted big stories to start with a bang. We were determined to follow any big story wherever it took us. The Mpiranya story was evidently a big one, especially given that we knew Zimbabwe had been harbouring him against its obligations under international law and the dictates of its collective conscience and humanity since 2002.

After settling down, Reid did not waste time before broaching the subject matter. He quickly said all the information and details they had gathered over time indicated Mpiranya was in Zimbabwe, hence he should be found dead or alive.

Reid summarised what was happening on the case, with Gwasira making intermittent interjections for clarifications and questions. The two looked at ease with each other and explained the issue coherently and with crystal clarity.

Reid said a UN investigations team had visited Harare after President Emmerson Mnangagwa had seized power through a coup in November 2017 to resume a probe which had stalled under the late former president Robert Mugabe’s regime which stonewalled the process.

Mugabe and his top political and military elites were determined to protect Mpiranya for joining forces with them against Rwanda and Uganda in the Congo War from 1998-2002.

While Mnangagwa was involved in the DRC War, his new government was reluctantly willing to cooperate with the UN as it wanted to end international isolation and its pariah status, and work with Rwandan President Paul Kagame.

The British, who supported the coup, wanted Mnangagwa to adopt the Kagame model — authoritarian-driven economic upliftment. I listened attentively — seeing where the story was going — until it was my turn to speak. Then I explained why Mpiranya is a big story to us.

I came to know of Mpiranya as a young reporter in the late 1990s when I closely followed and covered the DRC War. In the process, I went to the DRC twice with Zimbabwean delegations comprising officials, the military and journalists to get briefings on the war.

First we were taken there by the late Defence minister Moven Mahachi and later by his successor Sydney Sekeremayi, although Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s point man, who was Justice minister, was deeply involved. Yet the real stories came from government, military and intelligence sources.

Oasis Hotel, Quill Club and KGVI Barracks (now Josiah Magama Tongogara Barracks) in Harare became some of our best sources of war stories — some commanders and soldiers involved in the conflict that we knew drank there.

At one time we got a long fax with a list of names of Zimbabwean soldiers killed in action and missing in action, an indication that the war was costly in terms of lives and financially, and published them. Mahachi was livid.

At personal level, I had a friend, Irvine Ndou, who was a soldier and fought in the war. His war diaries and experiences were interesting, sensational and horrifying. He stayed at my place on several occasions before he went to Australia where he now lives.

As a result, I was one of the first reporters from the circumference of action to write about the first significant number of casualties and body bags to arrive from the war after a neighbour in Entumbane suburb in Bulawayo, where I lived, was killed in the conflict. After an hour of exchanges with Reid and Gwasira amid guarded optimism and new hope, we wrapped up the meeting with a joke — “he can run, but can’t hide”. Mpiranya that is.

We agreed to keep in touch while exchanging notes on the issue. Before the meeting ended, Reid gave me a document with names and phone numbers of Rwandans and Zimbabweans who were said to be part of Mpiranya’s network.

We later checked most of the numbers, including those supposed to be of his girlfriend, yielding valuable details. Soon after the meeting, I went up to the 10th floor at the rooftop of the hotel, where there was a sky bar which commanded sweeping views of the Nairobi skyline, the Westlands area and the neighbouring Nairobi National Park.

Perched on top of the luxurious five-star, sky lounge, one of the swankiest rooftop bars in Nairobi, has plenty of comfy lounge seats, colourful bar stools and cool lighting, while its open-air terrace around a swimming pool comes with breath-taking panoramic views, as well as a fresh breeze blowing across the bar.

Sophisticated yet chilled in atmosphere, the rooftop bar had a soothing effect which calmed my nerves about the dicey investigation and the smell of death from the virulent Covid-19 pandemic. I ordered a Tusker, arguably one of the best known beer brands in Kenya, sat comfortably on a couch and went on an imagination and thought odyssey about the journalism project we were launching and the sort of stories we should publish.

A friendly waiter from the bar serving me then interrupts my wistful imagination trip with a bizarre theory that Covid-19 did not kill black people, so I should not worry about it. There was no need for masks, she insisted.

She was nice, but I was not impressed with her idle story, although I politely engaged her to drive out solitude, asking why she thought like that. It was ironic to entertain her shaggy-dog story about Covid-19 as sometimes I prefer drinking alone quietly if I am thinking about serious things.

For me her Covid-19 urban legend was one of those zany stories that I had heard from delusional Zanu PF officials back home. Fortunately, Gwasira arrived to rescue me from the jaws of the gaslighting conversation as I drifted to the brink of cynicism.

We quickly switched from the waiter’s snake oil theories to serious stories about genocide investigations and social issues. Immediately we struck a chord on that and then drank jovially until they closed the bar.

During the meeting earlier in the day, it had transpired there were several other Zimbabweans involved in the Mpiranya case.

These included the late southern African director of Human Rights Watch, Dewa Mavhinga (pictured above), former Zanu PF MP and minister Jonathan Moyo and two local prominent lawyers who were providing consultancy services in the background, including contacts with former police and intelligence bosses who knew of the Mpiranya matter.

I did not meet Moyo while in Nairobi as he felt under siege, and cited security reasons for not venturing into the public. Mavhinga, always at the frontline of human rights battles, had brought in Moyo as a former high-ranking Zimbabwean government official into the process.

Moyo had already settled in Nairobi after he had escaped with his family and friends the deadly nocturnal gunfire during the November 2017 military coup which toppled the late former president Robert Mugabe, installing President Emmerson Mnangagwa in power.

Communication between Mavhinga and Moyo details how they came to work together on the issue, as well as how they linked up with Reid and Gwasira, joining forces with the lawyers who prefer to remain anonymous.

In one of the communications, Moyo tells Mavhinga that he was willing to help to ensure justice is not only done, but also seen to be done on condition that his security was guaranteed as the case was dangerous and his own safety had been compromised on many occasions by Zimbabwean security agents.

Moyo cites an incident in which his photos were taken off a closed-circuit television camera in a Nairobi residential complex where he lived and circulated on social media, and one in which his teenage daughter flying as an unaccompanied minor from Nairobi to Harare was accosted by intelligence operatives at Robert Mugabe International Airport, interrogating her about her family, especially her father’s whereabouts, and where they lived.

At one time, his security trailers also zeroed in on him through geolocation technology while he was sitting at a Nairobi restaurant. So he was justifiably paranoid.

Always at the vanguard of human rights defence, Mavhinga — who had previously recommended me for a Human Rights Watch Award (with US$5 000 prize money which was later frozen at my request) promised Moyo improved security measures and relocation elsewhere if needs be.

Although there was a US$5 million bounty on Mpiranya’s head, UN investigators said human rights accountability and justice should be the main motivation for investigators, witnesses and consultants than the money.

They mainly offered the bounty to entice those keeping Mpiranya and close associates to cooperate, which they did not. Moyo makes it clear in his communication with Mavhinga that he wanted justice and security, not the money. He says his security was far more important than anything else at the material time. For a long time, Moyo worked closely with Mavhinga, Reid and Gwasira.

He wrote detailed reports for the UN on Mpiranya which gave the process new momentum and traction. That energised Reid to make the final push against Mpiranya ahead of his new retirement date in 2021. For Reid, failure was not option.

By hook or by crook, he wanted to find Mpiranya dead or alive. So he scrolled down and navigated through chaotic masses of information and disinformation constituting Mpiranya’s digital file and footprint. Apart from the headache of handling tonnes of information, the Mpiranya investigation was fraught with danger. Moyo, Mavhinga, Reid, Gwasira and the lawyers were aware of that.

In fact, we all knew not only of the dystopian horrors of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, but also how Kenyan journalist William Mwaura Munuhe was killed by assassins while trying to help his country’s and American investigators apprehend another genocide fugitive, controversial businessman Felicien Kabuga.

After a failed attempt to trap Kabuga, Munuhe, who had fatally underestimated the Rwandan genocidaire’s reach and influence within the Kenyan intelligence community, was found dead in January 2003 at his upmarket Karen home.

Munuhe had made one great mistake: He had been dealing with Kabuga as a business associate, but selling him out to a powerful intelligence boss within the system, unaware they were friends. So Munuhe’s plot with Kenyan and American intelligence to trap Kabuga was ill-fated.

Two days before a planned 16 January 2003 business meeting to trap Kabuga, assassins, clearly hired by the Rwandan fugitive’s intelligence henchmen, stormed the journalist’s home and shot him in the head.

They then lit a charcoal stove, tucked the body back in bed and staged a suicide-death through carbon monoxide poisoning. Carbon monoxide poisoning occurs when the gas builds up in one’s bloodstream in a closed space.

After the murder, Americans released a revealing statement saying Munuhe was killed by hitmen for his hitherto publicly unknown role in the doomed bid to capture Kabuga. That shed new light into the epic hunt for the tycoon who even married his daughters to Habyarimana’s sons to cement proximity to power and leverage patronage for self-aggrandisement.

Yet Munuhe’s role in the issue was far more complex than just a mere investigation as he had become entangled in toxic friendships, enmities and betrayals — characterised by underworld money deals — involving Kabuga, Kenyan intelligence boss, Internal Security permanent secretary Zakayo Cheruiyot and intelligence networks.

Cheruiyot, who Munuhe had communicated with about Kabuga without knowing he was the Rwandan mogul’s top contact in the intelligence establishment, denied involvement in the murder. He said he did not know who Kabuga was, although he knew Munuhe. Besides Mavhinga and Moyo, there were other Zimbabweans from different walks of life who had been involved in the Mpiranya case after they had been roped in for various skills.

That is besides the security services, police, intelligence and the army officers, and government officials who were part of it. Western embassies were also part of the Mpiranya manhunt, and had their own processes.

Naturally, Rwanda was also deeply involved. In Rwanda, the genocide fugitives are monsters inc characters who must be found by all means necessary and jailed for life.

Reid indicated in our meeting and subsequent numerous conversations that his UN team had been engaging the Zimbabwean government over Mpiranya after Mnangagwa’s ascendancy. He said there were high-level official meetings and interactions which had been going on, although it was clear political and security elites were not co-operating or engaging in good faith.

Bureaucrats, who did not know much about Mpiranya, seemed well-intentioned in their actions. Reid had explained there was a Zimbabwean inter-departmental taskforce chaired by Foreign Affairs formed to investigate the issue.

It worked with the UN prosecution’s office at The Hague under chief prosecutor Serge Brammertz and held meetings with the investigation team to facilitate the probe. It also coordinated the investigations at various levels until the end.

As part of that, Reid has been to Zimbabwe and other countries in the region to co-ordinate the Mpiranya trail. However, there was scepticism given that even though Zimbabwe knew Mpiranya was in the country since 2002 it did not actively take measures to arrest him or report to the UN that he had died for reasons best known to its leaders.

The top brass never wanted to expose Mpiranya after fighting with Zimbabwe in DRC, so they protected him and lied about the issue before and after his death, although under pressure they occasionally said he had died.

The UN did not believe them, so it persisted with its own investigation. There were two theories: That Mpiranya was well and alive in Zimbabwe living under pseudonyms, while traversing the region on the run, and that he had died.

He had lived in various locations, including army barracks, Msasa Park, Norton and Kadoma, as well as at a farm in Shamva. The investigation took us to all those places, including refugee camps.

Reid kept an open mind, and insisted he wanted Mpiranya dead or alive to ensure that he was accounted for so that he would not cause any further harm. After that, he would say to us with a sense of wished-for satisfaction, I will happily go back to retirement in Australia.

A former New South Wales detective and ex-operations chief for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, he had tracked down and arrested more than 160 war criminals before retiring in 2018.

When the hunt for Rwandan genocide fugitives heated up after going cold for sometime, Reid crawled out of the retirement woodwork to get back on Mpiranya’s trail.

He had hunted down war criminals and terror suspects in Australia, including Nazis after World War II, having joined the NSW police in 1975 before becoming a detective in 1981, working with the homicide squad. So he knew his job required him to be as patient as an ox.

Not many people would wait for 15 or 25 years to achieve something. In his action-packed career, Reid worked in several capacities for the federal attorney-general’s office, which included the Special Investigations Unit set up to investigate suspects who entered Australia in the 1940s and 1950s after potentially working with the Nazis during World War II.

The unit was set up by former Australian premier Bob Hawke’s government from 1983-1991 in response to pressure from the Jewish community over an ABC News report that Yugoslavian and Latvian immigrants in Australia had worked with the Nazis.

Reid and his colleagues did not only substantiate the allegations, but discovered the situation was far more serious than had been reported. They set out in May 1989 to investigate and arrest Ukrainian Ivan Polyukhovich in South Australia.

He was then charged with war crimes in 1990. They travelled to the United States, Canada, Israel and the Soviet Union and excavated a mass grave site of up to 850 Jewish victims. All that evidence was presented in court, but the jury still found him not guilty of direct involvement in the massacres. He died in 1997.

Following his crime-busting and Nazi hunting days in Australia, Reid then spent 17 years at the helm of the investigative team at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia where he nailed Mladic who was convicted of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes in 2017.

He then retired in August 2018, before being brought back to trail Mpiranya and others. He worked indefatigably and his investigations led to the UN arresting Kabuga and resultantly discovering from a computer communication trail Mpiranya had actually died of tuberculosis in Zimbabwe in 2006 at West End Clinic in Harare, and was buried at Granville Cemetery (Mbudzi) on the southern outskirts of the capital.

I had remained part of that process, in touch with Reid and Gwasira until my phones and all valuables that I had on that day were stolen at gunpoint in an armed robbery incident in the crime-ridden Alexandra Township — Gomora — in Johannesburg at the end of January this year.

Coincidentally, a few days after that, former Zimbabwean Finance minister Tendai Biti, the main opposition Citizens’ Coalition for Change co-deputy leader, was robbed at Presidential Shop at Mandela Square in Sandton while he was buying his favourite Madiba shirts.

Still smarting from the robbery, I met Biti at Mandela Square walking like a zombie, badly spooked and looking depressed. He could not even see me. Briefly talking to him did not help. I could relate to his agony and exasperation after my Gomora experience, but I quickly let it go and moved on.

Had that not been the case, I would have been there in the thick of action on the periphery of the UN process all the way to Mpiranya’s grave where the case was closed after DNA tests. Zimbabwean officials — who are gifted with the DNA of lying — were left exposed and have been incoherently claiming they helped resolve the mystery.

The fact is they were acting in bad faith. This may have serious implications for Rwanda’s newfound cordial relations with Zimbabwe, especially Mnangagwa and his new role model, Kagame. Without dogged investigators like Reid, Zimbabwean officials who knew about the issue were prepared to go to their graves with the Mpiranya secret.

With their well-known love for power and money, which is why they will not let go of their ivory towers and trappings of office unless hounded out like Mugabe, not even the US$5 million bounty would have moved any one of them on Mpiranya’s case, to show that it was a high-stakes game for them.

Zimbabwean officials would not break the Mpiranya Omerta, a Mafia-style code of secrecy and silence which seals their lips even against their own interest. After some splendid work, Reid retired in 2021 — months before Mpiranya’s grave was located.

He was awarded Member of the Order of Australia in January for his ground-breaking service to international criminal investigations. With his great feats — stuff of legend, Reid retired as probably the best investigator in the world. He now lives on the Sunshine Coast. He enjoys playing golf, and spending time with his family in Queensland state, north-eastern Australia, whose capital is Brisbane where my friend Ndou lives on the south-eastern coast.

For Mpiranya’s victims, scepticism and a sense of travesty of justice linger on. But for Reid, all is well that ends well.

You may like