News

LONG READ: Trevor Ncube’s dalliances with Mnangagwa run much deeper

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksThis article on the mysterious and controversial relations between President Emmerson Mnangagwa and local publisher Trevor Ncube is a summary based on an extract from a chapter in a draft manuscript of a book titled Reporting Under Pressure: Truth in Perilous Times, which award-winning journalist Dumisani Muleya, The NewsHawks managing editor, is currently working on.

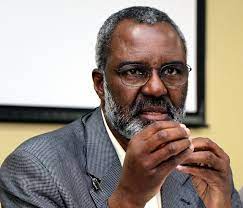

SOMETIME deep in the spring of November 2004 under the azure blue sky hinting at a summer about to set in, former Zimbabwean minister and ex-Zanu PF member of Parliament Jonathan Moyo received a surprising and curious message from his estranged friend Trevor Ncube, a local publisher then flying high the flag of independent journalism.

JONATHAN MBIRIYAMVEKA

The message rekindled a friendship that had gone sour and ended acrimoniously largely over the 1999/2000 Constitutional Commission process, which Ncube at the time had described as the “most expensive public relations disaster” since Zimbabwe’s Independence in 1980.

Moyo was a central figure in the commission’s Aegean task to draft a new constitution to reform Zimbabwe’s authoritarian dystopia that had been spawned by a catalogue of failures after the 1980 dream of a new beginning to build an inclusive, democratic and prosperous society had collapsed into chaos and disillusionment.

The constitutional process had set Moyo on a collision course with Ncube, civil society and the opposition at the time. Even some in Zanu PF circles were also against Moyo, who had been brought back from South Africa after sometime in Kenya by the late Zanu PF maverick, Eddison Zvobgo, tasked to superintend the process on behalf of the ruling party.

Zvobgo had been sent secretly to London, United Kingdom, to work on a Zanu PF draft constitution that was to be used as a document of engagement or even be manoeuvred into the official process through the backdoor. When confronted by two Zimbabwe Independent journalists about this issue at his Old Reserve Building offices in Harare in January 2000, Zvobgo, looking immaculate in a black suit, white shirt and black tie, stood up from his chair behind a palatial desk, went to get some coffee and then brought the secret Zanu PF draft constitution he had written.

In a jovial and sarcastic mood, he read out the preamble to the reporters and burst into characteristic self-praise, joking: “Listen, this is written in English, can you hear that; the Queen’s language, not what you are taught at the University of Zimbabwe or your colleges here! Ichi chirungu original, not zvenyu zvamunonyora izvi (this is original English, not what you write).

After some light-hearted moments, jokes and laughter, Zvobgo — who was cheerful amid clear signs of deteriorating health, which he said was due to a lengthy battle with cancer — then gave the reporters an insight into the constitutional commission process and the dynamics at play, admitting his agenda and that of his party, before diverting to Zanu PF internal politics.

On his part, he wanted to know how the journalists had known about the secret role he was playing on behalf of his party behind the scenes and his own political manoeuvres. Those in the constitutional commission who knew about the story had leaked it to the media to expose Zanu PF’s hidden agenda in the process; the late former president Robert Mugabe wanted it to be a charade to maintain his rule.

However, instead of doing Mugabe’s bidding throughout the exercise, Zvobgo had his own agenda which was to later play out as a spectacle in the commission’s theatre of debate and its manoeuvring chessboard at the height of attendant political brinkmanship.

The eventual fallout emanating from the constitutional reform process had far-reaching personal consequences for Moyo and Ncube, and dramatic political repercussions for Zimbabwe. Mugabe, who had already ruined the nation through leadership, governance and policy failures — although the worst was yet to come — had on 21 May 1999 appointed the commission to come up with a new constitution fit for the country to replace the repeatedly amended, hence mutilated, Lancaster House constitution.

Typically, Mugabe did not want reform, let alone change, but a smokescreen. He clung onto shibboleths of the past and concomitant certainties until his tragic end. The debate on constitutional reform was sparked by what was viewed as a series of arbitrary amendments to the Lancaster House constitution to consolidate and concentrate power in the presidency.

The most far-reaching of those was the 1987 amendment which created the executive presidency to build Mugabe’s imperial hegemony which lasted 37 years. Zvobgo was central to that. Many say he did Mugabe’s bidding not because he wanted him to be unconquerable and remain in power in perpetuity, but hoping one day he would succeed him as president.

Following the Meeting of Commonwealth Heads of State and Government held in Lusaka from 1 to 7 August 1979, the UK government under Margaret Thatcher — the first female British prime minister and longest-serving one in the 20th century — issued invitations to Bishop Abel Muzorewa, then Zimbabwe-Rhodesia premier, and leaders of the Patriotic Front — Zapu and Zanu (Joshua Nkomo and Mugabe respectively) — to participate in a Constitutional Conference at Lancaster House in London.

The purpose of the conference was to discuss and reach agreement on the terms of an independence constitution, and that elections should be supervised under British authority to enable Rhodesia to proceed to legal self-rule and the parties to settle their differences by political means via the first democratic election.

The conference opened on 10 September under the chairmanship of Lord Peter Carrington, secretary of state for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs. It ended on 15 December 1979, after 47 plenary sessions.

The resultant Lancaster House constitution became a ceasefire and transitional document to stop the liberation war and bloodshed which had been raging for over a decade.

After mismanaging the country through authoritarian repression, corruption and incompetence for almost two decades, Mugabe was in 1999 forced into the constitutional reform process by growing resistance and agitation from opposition parties and civil society organisations, especially the National Constitutional Assembly (NCA), whose taskforce was chaired by the late founding MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai.

Tsvangirai had been the leading light of the labour movement for the past decade. Established in 1997 at a time when Mugabe had begun losing political grip and traction as the economy declined and socio-economic problems mounted, amid rising discontent, even though he had been overwhelmingly re-elected the previous year due to lack of serious opposition, the NCA’s founding convenor was lawyer Tawanda Mutasah, now Oxfam vice-president of global partnerships and impact. Oxfam is a global organisation that fights inequality to end poverty and injustice.

Mutasah served as moderator. He was succeeded by Bishop Peter Nemapare. Serving with Tsvangirai in the NCA taskforce were lawyers and activists, who included Welshman Ncube, Lovemore Madhuku, Tendai Biti, Brian Kagoro, Everjoice Win and Priscillah Misihairabwi.

The chairperson of the state-sponsored constitutional commission was the late chief justice Godfrey Chidyausiku, then a Supreme Court judge. The commission had 396 members, including all 150 members of Parliament.

Some previous acerbic critics of the Mugabe government were also included among the 246 other members, including Moyo, who designed the structure, process and methodology of the constitutional commission and its work.

After months of intensive and controversial outreach programmes — well over 500 outreach meetings were held — a draft was produced and subjected to a constitutional referendum on 12 February and 13 February 2000.

The constitutional draft was rejected by the people. Moyo, who had become a key player in the constitutional commission, while in the process fighting Mugabe succession battles with Zanu PF gladiators like Zvobgo and Mnangagwa on opposing factions, was hugely disappointed. He could not breathe.

Meanwhile, Ncube and others in the NCA, opposition and civil society circles were over the moon. The rejection of the constitutional commission draft constitution had serious and far-reaching consequences that were to shape Zimbabwe’s politics for a long time to come.

The repercussions and impact of that referendum are still being felt up to this day. The negative outcome, especially over a clause giving the government power to seize white owned farms without compensation, was taken as a personal rebuff of Mugabe who was pushing for it and land reform after the expiry of the Lancaster House constitution’s 10-year moratorium.

Conversely, it was seen as victory for the NCA and opposition forces, especially the newly-formed MDC under Tsvangirai. The result gave the opposition momentum until the June 2000 parliamentary election, which the MDC lost by a narrow margin — five constituencies — on elected seats. That was a serious warning to Mugabe and Zanu PF that the honeymoon was over.

The constitutional process fallout triggered a serious political backlash by Mugabe — he let loose his supporters, led by war veterans — to grab white-owned farms in retaliation for the defeat, a process that would define the country’s future for generations.

White farmers had mobilised against the draft over the land issue in a bid to thwart farm grabs, but the law of unintended consequences applied. Their farms were violently seized, leading to the collapse of commercial agriculture, the economic mainstay and, resultantly, Zimbabwe’s economic implosion.

At personal levels, the process led to a breakdown in relations. One of the relations that became a casualty of the fight for a new constitution was that of Mugabe and Zvobgo, which was patchy anyway. Zvobgo, who had roped in Moyo through publisher and academic Ibbo Mandaza, wanted to use the constitutional reform process to stage a palace coup against Mugabe by barring him from standing for re-election. He had a grip on the transitional mechanism committee of the constitutional process chaired by lawyer Honour Mkushi.

Zvobgo campaigned indefatigably for Mugabe to be barred from standing for re-election through a constitutional mechanism and that led to a complete breakdown in relations. In the process, Zvobgo clashed not only with Mnangagwa and Chidyausiku, who were there to protect Mugabe, but also Moyo, who objected to the idea of ousting an elected leader through the backdoor of a constitutional reform process, instead of elections.

The fight between Moyo and Zvobgo, who had brought him in, became nasty to the extent that the Masvingo maverick’s allies stormed Sheraton (now Rainbow) Hotel in Harare, where the professor was staying for months, and threatened to bring down the hotel if their agenda was thwarted. Zvobgo’s allies, especially Dzikamai Mavhaire, had already been in trouble in Zanu PF for agitating that “Mugabe must go”.

A Harvard-trained lawyer, brilliant legal mind and Zanu PF spokesperson at the Lancaster House Talks, Zvobgo had been Mugabe’s co-partisan and close ally for decades.

They had fought together in the liberation struggle, detained in the same prison cells, shared food and, along with many others, emerged as heroes in 1980, yet their rivalry had remained bubbling under the surface, waiting to erupt.

Having helped Mugabe initially to build a one-party state and an imperial presidency, Zvobgo had tried to later on challenge him on policy issues, even on sensitive matters like Gukurahundi and demanding reform in public. His mercurial role in the constitutional commission became his last-ditch stand. He paid for it.

By the time he died on 22 August 2004, just before the Dinyane High School meeting in Tsholotsho on 18 November 2004 to coordinate Mugabe’s succession plot and Mnangagwa’s rise, Zvobgo had been booted out of top Zanu PF and government structures, including cabinet and the politburo. Mnangagwa defended Mugabe to the hilt during the constitutional commission.

Amid all this topsy-turvy politics, Moyo and Ncube’s friendship also became a casualty of the acrimonious process and its domino effect. They fell out badly. The situation became worse when Moyo was later appointed Information minister in 2000, after which he had subsequent serious run-ins with the media as he defended Mugabe and Zanu PF, leading their strategic communications and fighting dirty.

Ncube spoke about this hostility publicly and even wrote an opinion-editorial in one of his newspapers lamenting the acrimonious breakdown of his relationship with Moyo. So when Ncube reached out to Moyo four years down the line in November 2004, it was a major surprise to the latter.

But it did not take time for them to reconcile as they had been great friends before. After the Tsholotsho debacle, Mnangagwa’s allies, six Zanu PF provincial chairpersons Mike Madiro (Manicaland), Daniel Shumba (Masvingo), Themba Ncube (Bulawayo), Jacob Mudenda (Matabeleland North), July Moyo (Midlands), and the late Lloyd Siyoka (Matabeleland South) had been suspended and later banned for five years. Moyo was also ostracised by Mugabe before being fired as minister and from the ruling party the following year — February 2005 — ahead of parliamentary elections in April after he had decided to stand as an independent candidate.

He waged a big fight and went on to win, partly courtesy of Ncube, who mobilised financial and logistical support for him. Ncube did not do it as charity or out of friendship, but as a calculated political move.

The way Moyo was dismissed by Mugabe while relaxing at the Holiday Inn Hotel in Bulawayo and how he later responded was both dramatic and acrimonious, yet politically revealing. Ncube (Trevor) and Moyo had a long relationship going back to the late 1980s when the latter was a lecturer, and the former a teaching assistant at the University of Zimbabwe. In fact, Moyo was Ncube’s negotiator (munyai in Shona; umkhongi in Ndebele), who escorted him to meet the Muzuva family when he went to ask for the hand of their daughter, Eva Muzuva, in marriage.

When Elias Rusike recruited Ncube to join the Financial Gazette as assistant editor to Clive Wilson in 1989, Moyo was already a contributing columnist to the paper; having been roped in earlier by the editor. It was a great development for Moyo to have Ncube, his friend, assume a top position at the Fingaz.

However, Ncube was only recruited because Moyo had refused an offer from Rusike to be editor of the Fingaz. Rusike, who had bought the paper from Murphy after leaving Zimpapers, where he was managing director, headhunted Moyo — a trailblazing academic who was an outspoken critic of Mugabe — to be his editor and offered him a hefty package, but he rejected the job, saying he could not leave the university to join Modus Publications.

Instead, Moyo remained a Fingaz columnist. He also wrote a column, CashTalk with Dr Jonathan Moyo, in the late Herbert Munangatire’s Sunday Times. Rusike then went for Ncube. At one point Rusike actually wanted Mthuli Ncube, an economist and now Finance minister, to edit the Fingaz.

Even though Trevor Ncube was a media rookie when he was recruited, with no journalism training or reporting experience, Wilson wanted to groom him to become the editor. However, after Nyarota was removed as The Chronicle editor and transferred to Harare before being summarily dismissed in 1989 following the Willowgate corruption scandal, Rusike — who had worked with him at Zimpapers — hired him in 1990 to take charge of the Fingaz.

But he did not last long. In 1991, Ncube then became Fingaz editor. He was also fired by the late Rusike, a Zanu PF central committee member, in 1995. It became a blessing in disguise for him. The following year, 1996, Ncube was recruited by his former boss Wilson and publisher Clive Murphy — they initially wanted the late Mark Chavunduka as their founding editor — to establish the Zimbabwe Independent, which formed the foundation for Alpha Media Holdings (AMH), also publishers of The NewsDay and The Standard.

AMH also runs Heart & Soul. Before 2017, Ncube’s media empire included South Africa’s Mail & Guardian, which had a regional African edition.

Between 1993 and 1999, Moyo and Ncube’s relationship seesawed as the former left to work in Kenya for the Ford Foundation, making their contacts sporadic, until his return home from South Africa in 1999 for the constitutional commission project. Despite the distance between them, the shrapnel from Ncube’s divorce with Eva did not spare Moyo, not least because of his role as marriage negotiator; and the fact that many a member of the Muzuva family had over the years become his close relations in the communal African sense.

When reports of Ncube bashing Eva in their toxic marriage and calling her “a stupid Zezuru woman” appeared in the media in 1994 following court processes, Moyo was disturbed, and that partly further strained their relationship. Ncube is now married to Nyaradzo Muteiwa.

Meanwhile, Ncube — who has supported Zapu, MDC, the Third Way, Mavambo/Dawn/ Kusile, Alliance for People’s Agenda and Zanu PF in his peripheral political activism — got himself embedded in Mnangagwa’s factional business networks through the late innovative banker and Zimbabwe Investment and Development Agency chief executive Douglas Munatsi and their associate Oliver Chidawu, Harare provincial minister of state.

Ncube and Munatsi joined Wingate Golf Club in Harare at about the same time and that cemented their friendship. Chidawu, an entrepreneur, and Munatsi were part of a business network that supported Mnangagwa for decades.

Their paths converged on business, mainly at Heritage Investment Bank and later after it had merged with First Merchant Bank in 1997. Subsequent to that, Munatsi engineered a merger of Bard Discount House, First Merchant Bank, UDC and ULC companies operating across the southern African region, culminating in the creation of a regional bank, African Banking Corporation, now BancABC, of which he was chief executive, with Chidawu as chairperson until 2014.

As managing director of First Merchant Bank, Munatsi was instrumental in engineering bank funding for Ncube’s acquisition of 100% control of ZimInd Publishers, which ran the Zimbabwe Independent and The Standard, when Murphy and Wilson, founders of the company, disinvested.

Munatsi also supported Ncube’s acquisition of the Mail & Guardian in South Africa in 2002. The New York-based Media Development Investment Fund (formerly Media Development Loan Fund), which provides affordable debt and equity financing to independent media, mainly in harsh operating environments, played a role.

The UK Guardian Media Group had sold the M&G to Ncube ahead of many other monied competitors because they believed he would maintain its editorial independence and integrity, while ensuring its financial sustainability.

After Munatsi helped Ncube with money to buy ZimindInd Publishers, the AMH boss says the late banker, who became a close family member, took a lot of flak from Zanu PF circles for supporting him. Yet that had embedded Ncube into Mnangagwa’s business circles and political networks, a relationship that would manifest itself when he reconnected with Moyo in 2004 after the Tsholotsho Declaration fiasco and years later during the 2017 military coup.

The Tsholotsho incident was about Mnangagwa’s dramatic bid to become Mugabe’s co-deputy during the Zanu PF 2004 congress ahead of former vice-president Joice Mujuru before he was stopped in his tracks by the late retired army commander General Solomon Mujuru and his faction. Subsequent efforts by Mnangagwa to form an opposition party, the United People’s Movement (UPM), a project which Moyo drove, failed as he used that to spook Mugabe into ditching Mujuru and embracing him, especially after the Zanu PF Goromonzi annual conference in 2006. The Mujurus has tried to stop Mugabe in Goromonzi from being the Zanu PF presidential election candidate in 2008.

They pulled out all the stops to do so in 2007 when they forced him to hold an extraordinary congress in December that year to confirm his candidacy. Mnangagwa defended Mugabe under siege from the Solomon Mujuru and Dumiso Dabengwa-led onslaught.

Politburo minutes, obtained and published in the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper by its top journalists at the time, confirmed the story.

When all that failed, senior Zanu PF politburo member and former minister Simba Makoni quit the party to challenge Mugabe in 2008. Ncube supported Makoni. In the meantime, Mnangagwa continued pushing to gain control until Solomon Mujuru’s mysterious death in August 2011 and Joice Mujuru’s removal in December 2014.

That opened the pathway for Mnangagwa to power. Prior to that in 1999, Mnangagwa had been defeated by John Nkomo for the position of party chair when Zvobgo led a realigned faction to scuttle his bid. Nkomo went on to become vice-president after the death of Joseph Msika in 2009.

He died later in 2013. After the Tsholotsho fiasco, suddenly, as if there was no fallout backdrop to their strained friendship since the constitutional commission days, Ncube crawled out of the woodwork and reached out to his erstwhile friend Moyo through text messages, saying he had been impressed by his “principled support for Mnangagwa” in Tsholotsho.

Moyo was surprised as he did not know Ncube, who always claimed at the time that he believed in change from outside Zanu PF, also supported Mnangagwa way back then. Ncube said at the time, his gripe with Moyo was that he believed change would come from outside Zanu PF, while his friend thought the opposite.

After Ncube reached out to Moyo, they were friends, again, just like that. When Moyo ran as an independent candidate for Tsholotsho in April 2005 against Mugabe’s advice — leading to the late strongman saying “akaoma musoro sedamba kuti papata; he is strongheaded) — Ncube was one of the few Mnangagwa-linked business allies, who included John Mushayavanhu, Herbert Nkala and his nephew Edwin Manikai, to contribute funds and logistics to his campaign.

Given Ncube’s stinginess, it was a big deal for him to contribute to Moyo’s campaign. The stakes were high. Ncube did not help Moyo out of mere friendship, which had been strained anyway, but as a political manoeuvre supported by Mnangagwa trying to reconfigure Zanu PF politics to create a pathway to the top.

Ncube’s messages had swiftly unlocked money and logistical support for Moyo from Mnangagwa’s close allies such as Mushayavanhu, Nkala and Manikai, the President’s nephew, who was to later recruit him to become part of the Presidential Advisory Council, which the AMH boss quit recently with his sour-grapes speech early last month in the Drakensberg, South Africa. At that time, Ncube came out in the open to let the cat out of the bag — telling Moyo that he was supporting Mnangagwa and hoped that he would be President someday.

Ncube whined about how Mugabe and Mujuru had stymied and crushed the Tsholotsho move; he was also keen to know how Moyo had come to be involved in supporting Mnangagwa, who was an enforcer of the Gukurahundi which had killed his father.

A previously unpublished dossier obtained by Zimbabwe Independent and Botswana’s INK Investigative Centre, journalists in 2018 revealed Moyo’s father — Job Melusi Mlevu, a Zapu councillor then — was killed on 22 January 1983 in Tsholotsho. The report showed most of the people were killed for political and ethnic reasons through brutal attacks, bayonetting and gunshots, including pregnant women, children and the elderly.

Moyo told Ncube that he was part of an informal network in Zanu PF’s politburo and central committee, as well as other allies outside the party in civil society and opposition circles trying to find ways of tackling the emotive Mugabe succession and Gukurahundi issues.

He said that they had two reasons for supporting Mnangagwa in 2004. First, Moyo’s close networks had come to know that Mnangagwa was the stumbling block to resolving the Gukurahundi issue within Zanu PF and government; he always felt that he was the target of any and all initiatives to address the matter; he was also on the ropes because the Zvobgo-Mujuru-Nkomo alliance was on the ascendancy and ruling the roost.

Moyo even tried to introduce a Gukurahundi Bill in Parliament when he became independent MP. Zvobgo had started distancing himself from Gukurahundi. Years back in 1982, Zvobgo had secretly told the late Zapu heavyweight Cephas Msipa that Mugabe and Zanu leaders had resolved to kill on a grand scale and commit ethnic cleansing to impose a one-party state and also build an ethnocentric national project.

The decision was made at a Zanu PF central committee meeting in Harare on 31 December 1982. After the meeting, Zvobgo secretly told Msipa: “The decision was simply that let’s massacre Ndebeles”. This was just two weeks before the deadly Gukurahundi tsunami started formally sweeping across Matabeleland.

The trigger was Zapu leader Nkomo’s refusal in a tense meeting with Mugabe in mid-January 1983 to accept a formal one-party state proposal and to kowtow to him. Even the discovery of arms caches saga in 1982, used as a pretext for the military lockdown in preparation of Gukurahundi, came after a volatile meeting on 5 February 1982 between Nkomo and Mugabe, in which the former had rejected the one-party state proposal that his party did not want.

Mnangagwa was the enforcer. So, Moyo told Ncube that they wanted to placate Mnangagwa on the Gukurahundi issue; rather than threatening him or joining those whom he thought were after his head, they wanted to build confidence and trust with him as they saw him as the leader with the keys to resolving the emotive atrocities issues.

What they wanted was not his scalp, but his cooperation and willingness to take responsibility and lead the initiative to allow for truth, justice, reconciliation, compensation and healing for the victims. Second, Moyo told Ncube that because it had become clear that the presidency in Zanu PF had deteriorated into a Karanga-Zezuru sub-ethnic battle, they wanted to break the logjam by proposing a rotation of the presidency of the party between four major ethnic/sub-ethnic groups in Zimbabwe: Zezuru, Karanga, Manyika and Ndebele.

They said this was fundamental to Zimbabwe’s progress and stopping ethnic polarisation, divisions and conflict, amid political instability and economic collapse. Initially Mnangagwa seemed amenable to the initiative to an extent that he even encouraged the formation of UPM to push this and other major national initiatives for new politics to extricate Zimbabwe out of the crisis.

Moyo and others produced concept papers on these issues, but Mnangagwa turned them into briefing and intelligence reports for Mugabe and used them to scare him that there was trouble brewing in Zanu PF and in the country because of how the party and government had mishandled the Tsholotsho saga.

Mnangagwa had since 1980 been Mugabe’s intelligence kingpin and pillar of support. Once he fired him on 6 November 2017, the floodgates opened two weeks later for a coup on 14/15 November, and Mugabe’s tragic end.

To further scare Mugabe, threats were made that there would be demonstrations at the 2005 Zanu PF Annual People’s Conference in Esigodini, just south of Bulawayo. Mnangagwa’s trick worked on Mugabe, who instructed him to withdraw the 2004 amendment to the Zanu PF constitution which had provided that one of the party’s two vice-presidents should be a woman — benefitting Mujuru, while blocking her archrival.

Mnangagwa was surprised but got afraid to table a notice for that amendment, yet he had got Mugabe where he wanted him.

After the Esigodini conference, where he turned around his political fortunes after throwing his allies under the bus over the Tsholotsho incident, Mnangagwa did not want to hear about UPM, which then suffered a stillbirth and fell apart before it was launched; and worse, he did not want to hear about Tsholotsho or Gukurahundi.

The story ended there and then. The rest is history. Suffice to say during the 2006 Zanu PF Goromonzi annual conference, General Mujuru’s plot to stop Mugabe from seeking re-election in 2008 failed (he was only stopped by Tsvangirai, forcing him into a coalition government in 2009) and that marked the beginning of the general’s own tragic end — he died in a mysterious fire in 2011.

Later his wife, Joice, was ousted as vice-president in 2014 and replaced with Mnangagwa. It was thus not a coincidence that Ncube in his Drakensberg speech early last month cited the belief that Mnangagwa would be better placed to resolve the Gukurahundi issue as one of the reasons he supported the coup.

That was a theory he shared with Moyo way back. Ncube said he had supported Mnangagwa during the coup because he thought since he had worked closely with Mugabe and seen how and why he had failed, and was also instrumental in Gukurahundi, he was better placed to be the next leader and to resolve Gukurahundi.

In so doing, Ncube had aggressively and clumsily tried to curry favour with Mnangagwa by unethically pressuring his editorial team at AMH and intimidating editors and reporters to support his partisan political cause at the expense of editorial independence and audiences.

He even went to the extent of censuring editors in public at work meetings and denouncing them on social media platforms for carrying stories he did not like, and which did not fit or advance his agenda to support Mnangagwa.

Ncube knew that what he was doing was wrong as he seized editors’ smartphones before editorial review meetings that he chaired for fear of being recorded and exposed as Mnangagwa’s captured loyalist and gatekeeper prepared to push the envelope to support and please him at all costs. The seizure of editors’ phones became a new low for Ncube in his desperate editorial manipulation bid and push to suborn senior journalists.

This endangered editorial independence, credibility and impartiality, but editors and reporters — except those who supported the coup and were his tools for journalistic manipulation — studiously resisted his cajoling, pressure and threats.

That saved AMH’s editorial credibility and integrity. When exasperated by the journalists’ resistance, Ncube would attack his own editors and reporters on Twitter, and either mute or block those who did not agree with him, in brazen acts of intolerance.

Abraham Lincoln said: “Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s true character, give him power.” Further, apart from using Pac as an ingratiating platform, Ncube manoeuvred to worm his way around Mnangagwa by taking his coup editors to the President’s Office to pay homage and show solidarity; networking with the First Lady Auxillia and roping in the President’s son-in-law Gerald Mlotshwa to fund his online In Conversation with Trevor interview series. Mlotshwa was also supposed to end up as a shareholder in AMH, which badly needed capital injection as a technically insolvent entity.

All the while, Ncube persisted to gullibly and naively believe that Mnangagwa was “a listening president” and political messiah Zimbabwe had been waiting for when most people had seen through the coup smokescreen, especially after the 1 August 2018 Harare massacre, days after his controversial election to sanitise the putsch stink and gain legitimacy.

In his Drakensberg address, in which he unwittingly admitted he was politically unworldly, naïve and wrong, Ncube said he had realised Mnangagwa had failed and that the coup project would not end well as it was largely motivated by the pursuit of personal, ethnic and economic or financial interests by Mnangagwa and his faction.

So for those reasons and many others, Ncube jumped ship even though he had enjoyed the ride while everyone could see that the Titanic was headed for the proverbial iceberg crash. In fairness, some people rightly feel Ncube, who has previously supported Zapu, MDC, the Third Way, Mavambo/Dawn/Kusile and Alliance for People’s Agenda (Apa), should not be faulted for his political errors of judgement, as it is his democratic right to do so, and since experience is the best teacher.

After all, many Zimbabweans including the worldly in politics, had supported the coup as they were tired of Mugabe and hoped for the best, perhaps against hope.

In the wake of his recent quitting, which many in the political community say was underlined by a sour-grapes speech, whose narrative is unjustified beyond his personal interests and collapsing business fortunes with mounting debts and failure to pay his workers, Ncube has opined that his Damascene perspective about the November 2017 coup and Mnangagwa’s lack of commitment to reform is based on the Keynesian principle that when facts change, one should also change their mind.

Indeed, amid a recent storm of criticism about his self-righteous outburst against Mnangagwa and self-vindication, Ncube tweeted: “When the facts change, I change my mind — what do you do, sir?” Political and social theorists will not disagree with Ncube’s philosophical Keynesian defence that when facts change, one’s mind should also change. Otherwise, being dogmatic and fossilised does not help.

As American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould said: “Nothing is more dangerous than a dogmatic worldview — nothing more constraining, more blinding to innovation, more destructive of openness . . .” In politics, it is trite that theory follows praxis, and not the other way round.

But the question is: What facts have changed in terms of Zanu PF rule and Mnangagwa — and their attitude towards reform — to cause Ncube’s purportedly Keynesian change of mind?

Are the supposed changed facts about public policy, public interest and the public good, or Ncube’s personal circumstances and his self-interest — Rupert Murdoch-style — in this scheme of things? The answer to this was provided by Nkosana Moyo in November 2018 after Ncube had earlier quit his party, Apa, to support Mnangagwa and his Zanu PF coup faction.

When Apa was launched in June 2017, Ncube was part of it. But when the coup came in November 2017 — five months later, Ncube went back to base to support Mnangagwa and jump onto the gravy train for a slot on the feeding trough, but, as it now turns out, it did not end well.

Nkosana Moyo, certainly with Ncube in mind, said: “(Some) Zimbabweans are not fighting to change the system; they are fighting to be included in the system.” He was clearly not far from the truth.