Opinion

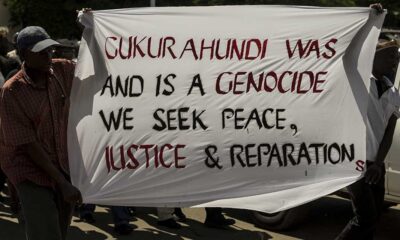

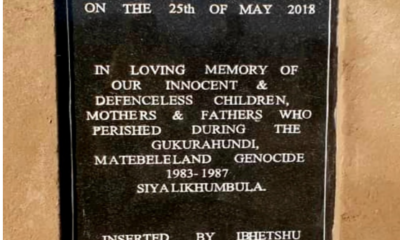

Gukurahundi in Zimbabwe: Epistemicide and genocide

Published

5 years agoon

By

NewsHawksWILLIAM J. MPOFU

Summary

THAT in political conflict and war the truth becomes a casualty that is sacrificed on the altar of expediency is an observation that is traceable to the ancient Greek tragedian, Aeschylus.

It is no accident that it had to be a student of tragedy and the workings of evil who noted how truth and knowledge are the first to be murdered before individuals and populations of human beings are slaughtered in armed operations by those that seek to conquer, dominate and rule others by hook or by crook.

The Gukurahundi genocide of 1983 to 1987 in Zimbabwe began with the desire by Robert Mugabe and his Zanu PF for one-party state rule under a life presidency. For that dark goal to be achieved, the political opposition in shape of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu) had to be eliminated.

All manner of political constructions, naming and labelling were conducted to create the conditions for and justification of an armed operation against Zapu and its leader, Joshua Nkomo.

The political and human identities of those that had to be eliminated were changed to enemies, dissidents, snakes and chaff itself.

On the Gukurahundi genocide, scholars have prevalently dwelt on controversies surrounding the numbers of the dead and the enduring effects of the killings.

This article is a consideration of the assassinations of the truth and knowledge, the epistemicide, which preceded, accompanied and followed the Gukurahundi genocide. Truth and knowledge die before, during and after genocide.

Introduction

It is an ancient piece of wisdom traceable to the Greek tragedian Aeschylus that in every conflict and war itself the truth and knowledge become the first victims.

Aeschylus, as one who pondered tragedy and the nature of evil, could not but make the observation that truth, knowledge and justice are frequently the casualties that are crucified on the altar of expediency when those that seek to conquer, dominate and rule others by hook or by crook have arrived.

The Gukurahundi genocide of 1983 to 1987 in Zimbabwe began with a desire and also a design by Mugabe and his Zanu PF for one-party state rule and a life presidency.

For the life presidency of Mugabe and the one-party rule of Zanu PF to be achieved, political opposition in shape of Nkomo and Zapu had to be eliminated.

Students of Zimbabwean history and politics, Masipula Sithole and John Makumbe (1997: 122), described how before and after Zimbabwe’s independence from Rhodesia a “one-party state psychology” possessed Mugabe and Zanu PF, turning the leader and the party into vigorous proponents of a one-man rule and one-party political regime in Zimbabwe where the political opposition became unwanted.

Nkomo and Zapu, under that tyrannical one-man and one-party political climate, came to be constructed as enemies and other undesirable objects that are legitimate candidates for elimination.

Mugabe and Zanu PF, Martin Meredith (2002: 60) observes, created what was a “one-party mantra” that was strong and brooked no debate or opposition.

Any individual or organisation in Zimbabwe that gestured towards multi-party democracy became an enemy that could not only be called names, but was supposed to be eliminated from the political landscape.

Instead of understanding Nkomo as a legitimate political opponent whose rights were to be guaranteed, Mugabe took him as “a self-appointed Ndebele king” who needed to be “crushed” (Mugabe in Meredith 2002: 60).

The reduction of Nkomo to a self-styled Ndebele king was at once a political insult and an effective metaphor that was meant to reduce an opposition leader from the nation of Zimbabwe to his tribe; the Ndebele, it was to expel him from national politics to the village.

Another Zanu PF stalwart, Edgar Tekere, put it more tellingly and more picturesquely, “Nkomo and his guerrillas are germs in the country’s wounds and they have to be cleaned up with iodine. The patient will have to scream a bit” (Tekere in Meredith 2002:60).

The truth and indeed the historical knowledge that Nkomo was another Zimbabwean freedom fighter and political leader was replaced with the damning condemnation that he was a national pathogen that like any contagion had to be eliminated from the national body-politic by use of painful disinfectants and antiseptics.

The genocidal wish is in actuality a desire that other people, as individuals and organisations, did not exist.

If they exist, as Nkomo and Zapu did, the determined desire becomes not only murderous but epistemicidal.

The human identity of the individuals, their organisations and populations is altered to that of objects and other undesirable organisms.

The truth and the knowledge die when people, on the basis of their political identity or historical origins, are reduced to killable and disposable objects.

Of the Gukurahundi genocide, much like other genocides, scholars, journalists and activists prevalently discuss the human dead and pay little or no attention to truths and knowledges that die before, during and after the genocide.

This essay is a consideration of how, in the Gukurahundi genocide, truth and knowledge were the first and continue to be the victims as the perpetrators and beneficiaries of the large-scale killings continue in denialism and impunity.

Violence of epistemicide

Perpetrators of genocide as non-revolutionary violence struggle to justify their acts that are otherwise not understandable.

Mahmood Mamdani (2003: 132) observes that genocidal violence is “violence that does not make sense, it is violence that is neither revolutionary nor counter-revolutionary”, but is just evil and self-interested.

Perpetrators of the Gukurahundi genocide had to work hard to give their acts some revolutionary air. Well before, and immediately after the independence of Zimbabwe from Rhodesian colonialism Mugabe and Zanu PF vigorously advanced the idea of a one-party state under a life president.

Mugabe in particular suggested that Zimbabweans needed to unite behind one nation, one party and one leader that would not have to suffer the inconveniences of multi-party democracy (Mugabe 1998).

The one-party state under a life presidency in Zimbabwe was a partisan political desire that could not be marketed to the world as such.

It was a political desire that did not sound revolutionary nor did it resonate with global aspirations of democracy. Joshua Nkomo and Zapu could not have been persuaded or pressured to exit the Zimbabwean political landscape to allow the unfolding of a one-party state regime under the life presidency of Mugabe.

It was not going to make any revolutionary or democratic sense to dissolve a whole opposition political party for purposes of erecting one-party state rule.

An image and knowledge of Zapu and Nkomo as undesirable and evil had to be constructed to justify their punishment.

Before Nkomo and Zapu were physically conquered and dominated, they had to be given a bad name that justified the violence against them.

The truth and knowledge about Nkomo and Zapu as legitimate political realities in Zimbabwe had to be assassinated and another image and political identity for them manufactured to justify their violation. Grosfoguel (2013: 73) explains how the genocides of conquest that preceded colonialism of the Global South in the Sixteenth Century employed epistemicides where the knowledges of and about the natives that were conquered had to be distorted if not destroyed.

Those that were eventually conquered and colonised were not called people, human beings and legitimate citizens of the earth but barbarians, primitives and uncivilised personages whose domination and exploitation was not such a crime. Before the Gukurahundi killings began, one of Mugabe’s ministers, Enos Nkala (2002: 60) declared that “as from today Zapu has become the enemy of Zanu PF”.

Zapu and its leader, Nkomo, had to be constructed as an enemy and Zimbabweans were mobilised to join the hatred, opposition and attack on this opponent. Genocide is not only the killing of people in large numbers but it also is the murder of truth and knowledge.

Both creativity and destruction accompany genocide in the way old political identities are destroyed and new ones created to create rational and justifiable conditions for the mass killing of those that have been constructed as enemies.

Emmanuel Eze (2005: 115) is correct to observe that no matter how evil and base perpetrators of genocide are, they invent an “ideology behind them” that seeks to give justification to their actions. What Eze (2005) calls the “epistemic conditions for genocide” is the active production of ideologies that are erected to give respectability to what actually is mass-murder and evil.

Genocidists invent and perform themselves as patriots and gallant revolutionaries. There is the violent work of concealment and erasure of knowledge that accompanies and also becomes part of the very identity of genocide.

Mamdani (2002: 7-8) identifies three silences that are part of the genocidal moment; the silence of history, of agency and of geography. There is a way in which historical origins and productions of genocide are concealed.

The tribal hatred of the Ndebele people in combination with the desire for a one-party state under Mugabe’s life presidency in Zimbabwe are part of the history that is silenced in the prevalent attempts to understand the Gukurahundi genocide.

The agency of Zanu PF led by Mugabe and that enjoyed popular support of a part of the Zimbabwean population is silenced when the genocide is reduced to a crime by a rogue political party and its leader not a popular movement.

Timothy Scannerchia (2011) notes the international geography of the Gukurahundi genocide where the United States of America and the United Kingdom, in the main, permitted the genocide by continuing to give financial and political support to Mugabe and Zanu PF even as the human rights violations and killings escalated in Zimbabwe.

An international political and social climate existed that permitted the killings of political enemies with impunity when superpowers that could have stopped Mugabe and Zanu PF did not only look aside but enabled them to kill political opponents in large numbers.

Scannerchia (2011) notes how Nkomo, his party and political supporters within the Zimbabwean population had become politically friendless to the extent that they had become dispensable in a country, region of Africa, and world that had other priorities than to stop a genocide.

Much like the colonised and the enslaved, victims of genocide are not killed as other legitimate human beings but are killed as abandoned and neglected objects.

This essay demonstrates below that Nkomo and his supporters were attacked not as other legitimate Zimbabweans and political subjects but as other things that included those that were constructed as dissidents and snakes.

A new language and knowledge of naming the victims had been constructed and was deployed. Roger Burbach (2003) narrates how in the massacres that followed the coup in Chile in1973, General Augusto Pinochet avoided referring to his victims as people, but gave them names of objects, animals and other undesirable or negligible things.

Naming the victims after undesirable objects and negligible things is itself the alteration of the truth, distorting of the humanity of those to be killed, and production of knew knowledge and political identities that enable victimisations and killings.

The lives of the condemned of genocide become what Judith Butler (2009) calls “ungrievable” lives whose termination, otherwise, is acceptable if not understandable.

Before they are physically dispossessed, displaced and massacred, victims of genocide like the colonised and the enslaved are epistemically reconstructed and reduced into disposable objects that, otherwise, should not be grieved.

What is notable here is that the genocidal impulse, which is the determined desire for the elimination of others, does not only produce many dead bodies but constructs a rationality of itself, and of its victims.

It is in equal measure a destructive and constructive impulse that builds a political and social universe where it is understandable and justified.

The “epistemicide” of colonial conquest that Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2014) describes about the way in which the West destroyed knowledges of the Global South in its march towards global domination is a telling example.

In order for Euro-centrism to be the rationality of the world, other rationalities of other parts of the world had to be discredited as falsehoods and superstitions.

The languages and knowledges of the conquerors and new rulers of the globe became the languages of humanity.

Since languages, histories and knowledges of peoples do not exist and walk on their own legs but are embodied by living people, their destruction also becomes a destruction of the people that carry them.

Epistemicide and genocide work together and fulfil each other. In the Gukurahundi Genocide, besides severe beatings and rape, “villagers were then forced to sing songs in the Shona language praising Zanu PF, while dancing on the mass graves of their families and fellow villagers killed and buried minutes earlier” (Meredith 2002: 67).

Forcing the Shona language on villagers that spoke other languages, including Kalanga, Ndebele, Tonga, Nambya and others, was the violent work of epistemicides that accompanied the genocide. Some decades after the genocide, the people of Matabaleland and the Midlands are complaining of the distortion and marginalisation of their languages and culture in Zimbabwe.

The combination of genocide and epistemicide kills people and their culture, and seeks to replace them with another people and culture, to create a new world in the absence of political opponents.

Further, epistemicide produces intentional ignorance of the truth and insulation from ethics and justice for the perpetrator of violence.

To imagine those that are being violated as, not people but things and undesirable objects, gives the genocidist some political and moral comfort.

Deliberate ignorance of the truth and justice in the scheme of epistemicide becomes an epistemology on its own where ignorance is produced as a knowledge of not seeing and not knowing the crimes that are being done and those that have been done.

In the important discussion of “the ignorance contract” where perpetrators of apartheid injustices in South Africa contracted themselves to ignorance about their crimes and in that way participated in “epistemologies of ignorance”, Melissa Steyn (2012: 8) observes how criminals and beneficiaries of the crimes against humanity insulate themselves from guilt.

Steyn illustrates the workings of ignorance contracting by use of a truth that circulates in the form of a joke about how in the whole of South Africa one can never meet a single person that agrees to have practiced or benefitted from apartheid discrimination and other injustices.

Denialism is the true refuge of the criminal against humanity. In that comic but also tragic way, apartheid in South Africa becomes a crime against humanity that has no criminals.

Epistemicide through the epistemology of ignorance makes intentional and convenient ignorance the refuge of the guilty. There is no government official or soldier in present Zimbabwe that admits to have been a perpetrator of the genocide.

“Breaking the silence” is part of the title of a report on the Gukurahundi Genocide published by the Legal Resources Foundation and the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace.

The title of the report bespeaks the strong silence that the Mugabe regime imposed on the subject of the Gukurahundi genocide where officially there has been no communication or accountability on perpetrators and justice for the victims.

The genocide was called a “closed chapter” by Emmerson Mnangagwa (2011: 1), the current president of Zimbabwe who was the Security minister when the mass killings happened.

Spoken by a key architect of the genocide, the metaphor of a “closed chapter” dramatises the determined official silencing, and epistimidal killing of the truth about the crimes against humanity.

When the truth and knowledge about the genocide cannot forever be silenced or denied, the genocidists can blame insanity itself. Mugabe publicly called the genocide a “moment of madness” (Holland 2008).

He explained the killings as having been what “was an act of madness. We killed each other and destroyed each other’s property. It was wrong and both sides were to blame. We had a difference, a quarrel. We engaged ourselves in a reckless and unprincipled fight” (Mugabe in Meredith 2002: 74).

To blame the genocide on madness and to include the victims as part of the wrongdoing was Mugabe’s way of cushioning himself from censure and guilt by distributing the blame and evening it out to the victims as having participated in and therefore being partly to blame for their victimisation.

Officially closing the chapter on the genocide, blaming it on madness and implicating the victims, has been the official way in which Mugabe and his party have sought to murder and victimise the truth and knowledge about the Gukurahundi genocide.

Activists that pestered Mugabe about the truth and justice were severely blamed for attempting not only to open old wounds but also for the crime of attempting to dig up dirty history in order to divide the nation.

“If we dig up history, then we wreck the nation … and we tear our people apart into factions, into tribes” (Mugabe in Meredith 2002: 74).

The grand ideals of national unity and peace are mobilised by genocidists to condemn their victims to silence about justice. The local and international media participated in silencing the truth about the genocide.

As people were being raped, killed and their homes burnt, “none of this was reported by the government controlled press; radio, or television, foreign press reports on the violence were dismissed as fabrications.

Evidence of atrocities collected by churchmen, doctors, and aid agencies and submitted to the government was ignored” (Meredith 2002: 67).

The reports by Amnesty International that highlighted the atrocities that were taking place were dismissed by Mugabe as a “heap of lies” and the international human rights organisation was renamed as “Amnesty Lies International” (Meredith 2002: 73).

From the Gukurahundi genocide of Zimbabwe, we can observe that genocide does not get called genocide by the perpetrators.

Other more palatable names for it are invented and circulated. The genocide itself is invented through excuses and pretexts that are concocted to justify it and also conceal the atrocities and other crimes that accompany it.

You may like