ZANU PF is going to its 7th elective congress which will, among other expected outcomes, choose the party’s first secretary and president, at a time the coup coalition which catapulted President Emmerson Mnangagwa to power has collapsed.

OWEN GAGARE

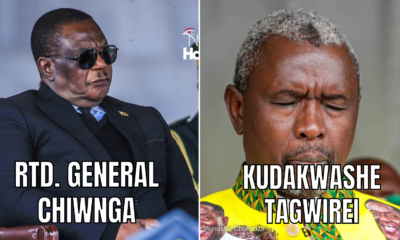

The bad blood, tension and mutual mistrust between Mnangagwa and his deputy Constantino Chiwenga — who feels betrayed by his boss — is the biggest indicator of the collapse of the coalition. Zanu PF insiders say although Chiwenga had over the years worked on challenging Mnangangwa after he showed signs he would violate an agreement to hand him power after five years at the helm, the former military general had ultimately not done enough and is unable to mount a challenge.

The congress, the first since the then president Robert Mugabe was deposed in a military coup in November 2017, will be held from 26 to 29 October 2022 at Robert Mugabe Square (also known as Freedom Square) in Harare.

Chiwenga was the commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces when the coup occurred, but he thrust Mnangagwa into power as part of a plan to soften the coup, which was termed a military assisted transition. He was the mover and shaker of the coup, with Mnangagwa playing a political role.

However, right from the onset, there was an understanding between Chiwenga and his military backers that Mnangagwa would be in power for five years before handing power to the former military general.

Chiwenga traded his military fatigues for suits after the coup following his appointment as vice-president, although Mnangagwa preferred to appoint Oppah Muchinguri as his deputy, which was seen as a first sign at somersaulting.

As per the unofficial coup agreement, the Zanu PF congress was supposed to confirm Chiwenga as the next Zanu PF president and first secretary, as well as the party’s candidate in next year’s general elections, but Mnangagwa is seeking re-election.

As reported by The NewsHawks several times, no sooner had Chiwenga assumed power than he started consolidating his grip by — among other tactics — purging Chiwenga’s allies, setting the stage for a power battle between the two gladiators.

Tension and mistrust between Mnangagwa and Chiwenga have been building up since the early days of the coup, as the two disagreed on cabinet and Zanu PF appointments, among other decisions.

The June 2018 bombing at White City Stadium in Bulawayo also heightened the tension between the two leaders. Mnangagwa’s backers believe he was the target of the White City bombing, which they insist was an inside job.

In violation of the coup agreement, Mnangagwa wanted to appoint Oppah Muchinguri his deputy, but Chiwenga demanded the position. Initially he wanted war veteran Victor Matemadanda to be appointed the Zanu PF political commissar, but his deputy insisted that the position be given to his close ally, retired Lieutenan-General Engelbert Rugeje. Mnangagwa also entertained forming a transitional government which would incorporate several people, among them former Zapu president Dumiso Dabengwa, but the idea was shot down by Chiwenga and his military backers, who wanted control.

Mnangagwa, however, took advantage of Chiwenga’s health woes to purge his allies from government and the military, often while his deputy wass seeking treatment outside the country, thereby strengthening his hand.

The Covid-19 pandemic also rattled the Chiwenga faction as it eliminated some of his strongest allies such as retired Leutenant-General Sibusiso Moyo, who was the face of the coup, after announcing the military action as well as former Air Force of Zimbabwe commander Perrence Shiri.

Mnangagwa and his supporters started pushing for the President to remain in charge beyond 2023 as early as December 2018 during the ruling party’s Esigodini annual conference.

Prior to the push, Chiwenga and others had been shocked to see Mnangagwa announcing in an interview in September 2018 during the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York that he would seek re-election in 2023.

Mnangagwa’s power consolidation drive gained momentum following Shiri’s death in July 2020 and Moyo’s death in January 2021, given that the two were critical political cogs in the Chiwenga faction. After Shiri’s death, Chiwenga and his army-driven faction pushed for his replacement with a person with a military background, but Mnangagwa appointed his ally from Masvingo, Anxious Jongwe Masuka.

One of Mnangagwa’s key strategies has been to mainly appoint his ethnic Karanga homeboys, mostly from the Midlands and Masvingo provinces, into key positions, as part of a power consolidation strategy. Chiwenga, Shiri and Moyo were critical in the planning and execution of the 2017 coup.

Besides being the face of the coup, Moyo was one of the key architects of the operation against Mugabe and worked hand-in-glove with Chiwenga when he was in charge of the military’s business units, which became central in building a war chest to execute the mission.

After assuming power, Mnangagwa unleashed a wave of purges in the military, police and Central Intelligence Organisation targeting Mugabe and former first lady Grace Mugabe’s allies first, before going for Chiwenga’s loyalists. Key commanders — who pivoted the coup, including the commander of the Presidential Guard battalion retired Lieutenant-General Anselem Sanyatwe — were removed in February 2019, while Chiwenga was battling ill-health in India.

Commanders retired ahead of diplomatic assignments included former Zimbabwe National Army chief-of-staff retired Lieutenant-General Douglas Nyikayaramba, who was chief-of-staff responsible for service personnel and logistics.

Nyikayaramba also succumbed to Covid-19. Other casualties were retired Lieutenant-General Martin Chedondo and retired Air Marshal Sheba Shumbayawonda. In May 2019, Mnangagwa then appointed Sanyatwe Zimbabwe’s ambassador to Tanzania, while Nyikayaramba was posted to Maputo, Mozambique. Chedondo was sent to China.

Sanyatwe had a personal relationship with Chiwenga to the extent that he flew from Tanzania to assist him finalise his divorce proceedings with his former wife Marry Mubaiwa.

Sanyatwe presented the Mubaiwa family with Chiwenga’s divorce token (gupuro), a traditional way of confirming that a marriage is irretrievably broken. Another big blow for the Chiwenga camp was Rugeje’s removal from heading Zanu PF’s critical mass mobilisation political commissariat.

Rugeje operated in the war room during the coup. Soon after the coup, Chiwenga arm-twisted Mnangagwa to appoint Rugeje as political commissar ahead of his preferred candidate Victor Matemadanda, albeit temporarily.

Mnangagwa later removed Rugeje from the position before appointing Matemadanda in June 2019. Mnangagwa’s cumulative manoeuvres appeared to have shifted the balance of power in Zanu PF in his favour, although Chiwenga had an upper hand after the coup.

The political war of attrition between Mnangagwa and Chiwenga found expression in the President’s controversial biography titled A Life of Sacrifice: Emmerson Mnangagwa, which book reviewers and political analysts say exposed the widening rift between the two. It was launched in August last year. The 154-page biography, which Mnangagwa described as a “brief window” into his life, was authored by Eddie Cross, a former opposition MDC high-ranking official and MP.

The book is a hagiography for Mnangagwa which depicts Chiwenga in negative light through its narrative.

Cross, Mnangagwa’s biographer and newfound loyalist, said the President would brook no nonsense from those threatening his grip on power, seen as warning to Chiwenga. Mnangagwa, who at the time of the coup had fled the country to South Africa after his mentor-cum-tormentor Mugabe had hounded him out, only returned after Chiwenga led the coup that sent Mugabe packing. Mugabe later described Mnangagwa as his “tormentor”.

The book, which has been reported on by The NewsHawks since launch, reveals that Chiwengwa’s appointment as co-deputy, together with Kembo Mohadi (who would later resign in 2021 after a sex scandal), was part of Mnangagwa’s coup-proofing ploy.

Mnangagwa appointed General Philip Valerio Sibanda to succeed Chiwenga as commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces. Sibanda, according to the book, is “possibly the best soldier in southern Africa and a man that was deeply respected in the army”.

“Mnangagwa’s actions drew little attention, but what the President was doing was closing the door on any possibility of the military -assisted transition (military coup) being repeated. He needed to know that the security services were led by men in whom he had confidence as professionals,” the book says.

Differences between the two have now divided the party down the middle, leaving it regimented into two major factions.

The Mnangagwa group is mainly Midlands and Masvingo provinces-based, while the Chiwenga one has threads cutting across different regions, although its main base has roots in the three Mashonaland provinces — Mashonaland East, Mashonaland West and Harare.