Opinion

What happens when Zanu PF faces an existential threat

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksALEX MAGAISA

AS the Citizens’ Coalition for Change (CCC) basks in the glory of its early gains across the country, it is important to remember that they are dealing with an adversary that has no scruples.

Even in ordinary times, Zanu PF goes for low blows. And when the tide is against it, Zanu PF bristles, ready to pounce on anything in its way. With only a couple of weeks before the by-elections and just over a year before the crucial general elections, the stakes could not be any higher.

Already, there are signs of deploying dirty tricks such as restricting political freedoms and violence are evident. Electoral watchdogs in formal and informal spaces have their work cut out but, as this article examines, there are worrying signs of hesitation by those carrying the duty to keep a watchful and frank eye on the electoral processes. They must step up and speak truth to power if they are to avoid being political laundromats for authoritarians.

Political laundering

Political laundromats sanitise the reputation of authoritarian regimes. Political laundering, like its counterpart money laundering in the financial sector, is a process where dirty political reputations undergo a cleansing process, making them look cleaner than they are. The most obvious political laundromats are media organisations that do propaganda, heaping unearned praise while ignoring the repression and corruption of the regime. State-related actors like the ZBC, the national broadcaster, and Zimpapers which publishes The Herald, The Sunday Mail and The Chronicle, among other titles, are typical political laundromats that specialise in cleaning the reputation of the regime. The Daily News has joined that stable in recent years. Those who invest in them are enablers of this process of political laundering.

On the international scene, political laundering of authoritarian regimes is performed by wealthy international public relations and lobbying firms. The Mnangagwa regime has invested millions of dollars in Western public relations (PR) firms under the guise of promoting re-engagement with the West. Non-state actors including civil society organisations (CSOs) also risk assuming the role of political laundromats when they deliberately restrain themselves from speaking truth to power or ignore or underplay blatant violations. It is easy to recoil in fear when operating in a repressive environment. They contribute to political laundering through self-censorship or under-reporting of repression and corruption. It is within this context that we analyse the current conduct of the Zimbabwean regime and how it has been reported.

Banning the CCC’s rallies

Zimbabwean police have banned the CCC from holding its by-election rally in Marondera last weekend.

The police are also understood to have banned another CCC rally scheduled for Binga in Matabeleland North province. This follows another ban of a rally in Gokwe two weeks ago. Although a High Court judge overturned the police ban on that occasion, the CCC was unable to hold its rally as local police ensured it did not happen by disrupting the gathering. The police have also tried to impose highly restrictive measures on rallies held by the CCC. These measures are very different from how the police treat Zanu PF rallies which are generally unconditional. Still, the presence and defiance of thousands of people who came to Gokwe were more than enough to demonstrate the CCC’s pulling power.

The banning of CCC rallies indicates a clear pattern that is familiar in authoritarian environments: the ruling party will use state institutions and the cover of law to stifle its rivals. During the election campaign, no other party has been subjected to similar rally bans or restrictions as the CCC, but the police can still wave the Maintenance of Order and Peace Act as justification for their actions. Zanu PF has never been stopped from holding its rallies in the same places that the CCC is being denied. The different application of rules by the police is yet another demonstration of the weaponisation of the law. Law is applied selectively to give an unfair advantage to Zanu PF by denying the CCC opportunities to carry out an effective campaign.

All this is testament to the early success of the CCC after its dramatic entry into the political arena in the last week of January. Zanu PF had hoped to go into the by-elections against a battered and mentally exhausted MDC Alliance. It had not budgeted for a new kid on the block that would fundamentally disrupt the political market. Where the Zanu PF regime used to target the MDC, it must now contend with the CCC with all the energy and adventure that it brings to the political market. The numbers that Nelson Chamisa and the CCC have pulled in the rallies held in Harare, Bulawayo, Gweru, Kwekwe, and Gokwe so far have spooked the regime. After two years of trying to decimate Chamisa and his allies, their resistance and resurgence have confounded the regime and caused panic.

Existential threat

It is clear to Zanu PF that the CCC poses a political threat of existential proportions. In other words, the very existence of Zanu PF is at stake. And anytime that Zanu PF faces an existential threat, it responds in a typically ultra-defensive and often brutal fashion. The first response is to close ranks and defend common interests. While it is true that there are competing factions within Zanu PF, when they face a common threat, they put aside their differences and usually find common ground to defend their looting space.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s first term is nearing completion. The military general who led the coup that toppled Robert Mugabe, Constantino Chiwenga, has been lingering rather impatiently for his turn. But Mnangagwa’s desire to carry on has long been a source of latent tension with the ambitious but fragile lieutenant who also wants a piece of the cake. After all, it is he who risked his life and liberty to bring it to the table when Mnangagwa was hiding in the safety of South Africa. However, while both men have contrasting personal political ambitions, Chamisa and the CCC represent a common threat to both of them.

It has become more apparent in recent weeks that neither of these two older men can legitimately win a free and fair election against the young opposition leader. In the absence of a political deal, they are united by their need to resort to political skullduggery to protect their common turf. Between each other and Chamisa, the latter is the greater enemy who must be resisted at all costs.

Their factional fight can resume later. As Chamisa navigates the political landscape, he must know that the two men are closer to each other than they are to him, their differences notwithstanding. He is the outsider who is threatening to grab the pie from right under their mouths and they will gang up against him.

The second type of response, which is part of the political skullduggery, is to raise the authoritarian factor to stifle Chamisa and the CCC. This includes using the coercive apparatus of the state to prevent Chamisa and the CCC from carrying out political activities.

This explains the recent spate of police bans on the CCC’s political rallies. The authoritarian factor is also apparent in the partisan media coverage, with the state media giving a disproportionate amount of time and positive messaging to Zanu PF. There is an increased use of repressive power, just to thwart the perceived existential threat posed by the CCC. Indeed, the CCC must brace itself for more repressive strategies from the dictator’s playbook.

The third type of response is the use of political violence. Zanu PF does not care about opposition parties that pose no threat to its hold on power. That is why it treats the MDC-T led by Douglas Mwonzora with much favour. It does not regard it as a political threat. If anything, the MDC-T is both a shield and a sword in the hands of Zanu PF – a shield because by giving it airtime and treating it kindly, Zanu PF creates a defence against accusations of partisanship; but a sword because Zanu PF can rely on the MDC-T to spend most of its time attacking the CCC.

The killing of CCC supporter Mboneni Ncube at the Kwekwe rally exemplifies the extent to which Zanu PF is prepared to go to defend its status. Many others were injured in that incident which was instigated by Zanu PF supporters. This brutal killing followed irresponsible statements by Chiwenga the previous day when he threatened to “crush” opposition supporters like “lice”. Previous genocides have been preceded by such hate speech by leaders.

This followed the tear-gassing of CCC supporters by police in Gokwe and Kwekwe and the beatings and arrests of other supporters in Harare. CCC vice-president Tendai Biti’s home was also attacked, leading to the assault of his staff member who was left severely wounded. CCC national spokesperson Fadzayi Mahere was attacked by a gang of assailants who sped away with her possessions. The regime will probably dismiss it as criminal activity but, in the circumstances, there are legitimate concerns that it is a politically targeted attack.

These incidents of violence are worrying signals of what is likely to come, especially as Zimbabwe prepares for the general elections in 2023. If a small set of by-elections that have little bearing on the balance of power can result in so much violence which involves death and serious injury, one can only imagine how this will play out as major elections loom where power for the next five years will be decided. The stakes will be a lot higher in 2023, and this can only lead to an escalation of political violence if Zanu PF senses, as it surely must, that power is at risk of slipping away.

The problem for those operating in repressive environments is that the Russian war in Ukraine has taken centre stage and it is likely to do so the longer it goes on. With the eyes of the world on Ukraine, and no one restraining them, dictators around the world are going to have a field day.

Even Zimbabwe’s neighbour, South Africa, which has dismally failed to deal with a problem at its doorstep, has latched onto the Ukraine crisis, fancying itself as some sort of mediator. The risk that the Zanu PF regime will fully switch on the apparatus of violence in the run-up to the 2023 elections while both global and regional attention is turned elsewhere is very real.

CSOs as watchdogs

In this context, the role of local civil society organisations assumes greater significance. While Zimbabwe’s constitution has an entire chapter dedicated to institutions designed to support democracy, most of them have been woefully inadequate. It is either they are grossly under-resourced or they are captured by the ruling party. Therefore, instead of acting as effective watchdogs of the state and its organs and supporting democracy, these institutions have become enablers of authoritarianism.

In the absence of effective watchdogs envisaged under the constitution, non-state actors such as CSOs assume a greater role and they have done a great deal over the past few decades. The story of Gukurahundi as it is known today would be different if organisations like the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, the Legal Resources Foundation and the Lawyers for Human Rights, an international organisation, had not stepped up to document the gory details of the atrocities. The Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights (ZLHR) continues to be a marquee example of a CSO that is vigilant and active in defending rights and freedoms whenever they are threatened by the state.

The Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum, ZimRights and the Zimbabwe Peace Project have shown great initiative and leadership in recent years.

The situation concerning electoral matters however needs urgent attention. The Zimbabwe Election Support Network (Zesn) and Electoral Resource Centre (ERC) have provided leadership in this area for a long time. This is why a review of the latest election observation report by Zesn is underwhelming. Someone unfamiliar with the ongoing political developments might think that circumstances leading up to the by-elections are mild and that the risk of political violence is minimal when in fact there has been a brutal killing at a political rally and there is an escalation of repression by the Zanu PF regime.

Weakness of voter registration

Zesn is a long-term election observer, which places it in an important watchdog role over the political and electoral processes. Its latest report, published on the Kubatana website, covers the last two weeks of February. While the report states that the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec) conducted the first phase of its mobile voter registration exercises, it has only a superficial reference to the problems associated with this important exercise. The lack of national identity cards is a key issue that the report refers to, but the enormity of this handicap, especially for young voters, could have been given more prominence.

The practical bottlenecks, such as the long queues and frustrating delays are not highlighted. In some cases, people reported that Zec was not present in places where it had announced that it would be conducting voter registration. These issues do not appear in the report. Zesn’s observers might say they did not witness these things, but it may be that their monitoring was not comprehensive enough to detect these weaknesses. There is a reluctance to be critical of Zec, although its performance has been dismal.

No word on the voters’ roll

Having commented on voter registration, the expectation was that the Zesn report would say something on the state of the voters’ roll. This is particularly important given that this has been one of the most topical issues during the pre-by-elections period, with a lot of concerns over the state of the voters’ roll. It is the document that determines whether citizens can vote in the by-elections. Indeed, Zec has been forced on more than two occasions to make official statements in response to concerns over the voters’ roll. There are several allegations concerning the high number of duplicate entries, unauthorised movement of voters from their constituencies and wards, and changes to information on the voters’ roll which have been highlighted by citizens and social movements such as Pachedu.

Zec has, rather incredibly, tried to dismiss the voters’ roll that it issued, claiming that it was leaked. Another Zec commissioner has claimed that the chaotic voters’ roll which has been the subject of much criticism was only a “draft”.

But this is inconsistent with the legal requirement, which is that there must be a final voters’ roll within a specific period before the next election. Indeed, Zec has used this rule to disqualify an MDC-T candidate on the basis that he was not registered before the closure of the voters’ roll. How then can he be disqualified when Zec claims the voters’ roll to have been a draft?

All this highlights that there are serious concerns over the voters’ roll. Yet amid this chaos, the country’s premier electoral watchdog has not a single word on the voters’ roll. The problem with these glaring omissions is that they create a false picture of normalcy. It is as if voter registration went ahead and there is a credible voters’ roll when in reality there is none. If there are questions over the voters’ roll, as there are, electoral watchdogs should highlight them. If they do not talk about them, people might think they are burying their heads in the sand. Electoral watchdogs should not fear offending Zec. Citizens whom they represent expect them to be their leading voices in these matters.

Lacking boldness

One of the problems with this report is its lack of boldness in highlighting the source of problems affecting the electoral environment. There seems to be a timidness that restrains Zesn from naming Zanu PF as the trouble causer. For example, in one part the report states that some “people were generally afraid to talk about politics and were attending some rallies out of fear of possible victimisation if they did not attend”. The culprit that uses such methods is known. It can never be the opposition because it cannot victimise the ruling party. Although the report refers to the issue of access to the media, there is nothing to demonstrate the blatant bias in favour of Zanu PF, itself a perennial problem that has been raised by election observers in the past but has never been addressed.

Lightening political violence

On electoral violations, despite there being a cold-blooded killing of an opposition supporter by named Zanu PF supporters, the Zesn report starts with a mild statement saying, “cases of electoral violations were minimal”. Perhaps it reflects the extent to which political violence has become normalised — that an electoral watchdog relegates the murder of a political opponent to the margins of the narrative. A single politically motivated killing should be serious enough to warrant a big red flag in the report of an electoral watchdog. Instead, the report describes it in the following terms: “The worst case that was reported was the altercation between suspected ruling party supporters an those of the CCC party which resulted in the death of one person, at a CCC rally in Kwekwe”. That’s all the electoral watchdog had to say on this blatant political murder and the report moves on to other issues. Clearly, the matter is not treated with the seriousness it deserves. There are several problems with this reporting:

It trivialises the circumstances of the death as arising from an “altercation” between the ruling party and opposition supporters.

This is grossly misleading because it gives an impression of parties that bear equal responsibility for the death. This was a situation where ruling party supporters unlawfully invaded an opposition political rally and used force against its supporters to cause fatal harm and severe injuries. They had no right to be there, and they were the provocateurs and aggressors. To describe it as an “altercation” is to minimise the blameworthiness of the Zanu PF aggressors and to gaslight the victims who are made to shoulder responsibility for their situation. It was an unlawful attack, not an altercation and an electoral watchdog should be bold enough to report these facts.

The irony is that the Zimbabwe Republic Police, which is notoriously partisan, did a better job than the electoral watchdog in reporting the circumstances of the murder. It treated the victim Mboneni Ncube with respect by naming him, something that the Zesn report does not even do. The police also named the accused persons, making it clear that they were Zanu PF members who unlawfully entered a CCC rally. Anyone reading the police memo would have a clear picture of who was to blame for the political violence. But the Zesn report presents a mild and sanitised picture that vaguely refers to “ruling party supporters” who were party to an “altercation” with CCC supporters. The irony is that Zesn had all this information from the police when it compiled its report, and yet, somehow, its report is more hesitant than the police report.

Furthermore, the Zesn report makes no mention at all of the several victims of injuries caused by the Zanu PF aggressors at the rally. Surely, Zesn’s observers who were at the rally would have witnessed these injured parties. In any event, one did not have to be at the rally to know that there were scores of victims who were impaled and struck with weapons by the Zanu PF supporters. If anything, this politically motivated killing should be a big highlight in the pre-election report, signaling a red flag that needs to be carefully watched as Zimbabwe hurtles towards the next general elections.

Finally, there is no mention of the incendiary statements made by vice-president Chiwenga before the Kwekwe rally at which Mboneni Ncube was slain. Chiwenga had likened opposition supporters to “lice” that would be “crushed”, a violent metaphor that constitutes hate speech. That it preceded the killing of an opposition supporter is worrying as it may be treated as unlawful incitement of violence. As already stated, genocidal periods have been preceded by the use of hate speech like that and one would expect electoral watchdogs to raise concerns over the use of such language in the context of electoral contests, especially given the history of political violence. Interestingly, the Zesn report recommends that “political parties desist from using hate speech and insightful language” (sic) and yet its report omits detail that informs this important recommendation. Did they accidentally omit or remove the section of the report that described the use of hate speech and inciteful language?

Conclusion

The by-election campaigns have revealed worrying signs of a violent political process leading up to the 2023 elections. The killing of Mboneni Ncube in cold blood by Zanu PF supporters who invaded a CCC rally is not to be taken lightly. It is a politically motivated murder whose consequences could prove dire for the legitimacy of the 2023 elections. If perpetrators are not held accountable, it will only give licence for more political violence. The banning of the CCC’s political rallies, while Zanu PF and the MDC-T have a free pass, is a sign of the selective application of the rules.

Most of the political referees provided for in the constitution are compromised. They lack independence from Zanu PF and the men and women who run them do not have the courage to hold the ruling party to account. In the absence of these constitutional restraints, the last guardians are to be found in areas such as the media, civil society and intellectuals. They have an important duty to challenge the partial narratives promoted by the regime and its surrogates; to challenge the abuse of law.

Some of these battles, such as legal battles in the politicised judicial arena, might seem like lost causes, but it is important to keep knocking on the door and, if anything, to challenge the courts to make decisions.

However, civil society organisations, whose own existence is under threat from a retrogressive Bill currently before Parliament, have a key role to play. They might try to play it safe by using mild and sanitised language when reporting electoral malpractices and political violence, but this will not save them from the authoritarian regime. Appeasement towards authoritarian regimes always fails in the end because these regimes keep turning the screws. If CSOs are not bold enough, they risk being perceived as political laundromats for the authoritarian regime.

About the writer: Dr Alex Magaisa is a law lecturer at Kent University in Britain and former adviser of Zimbabwe’s late prime minister Morgan Tsvangirai.

You may like

-

Diaspora Praise Without Diaspora Rights Is Political Dishonesty

-

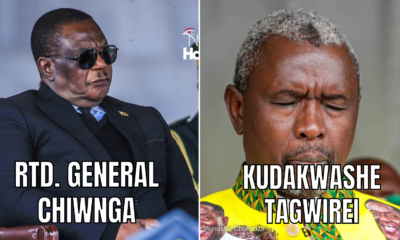

Tagwirei Leverages Money On Succession

-

ZANU PF’s Succession Politics, Is Not a Contest of Ideas but a Struggle for Access

-

Tagwirei at Zanu PF DZ meeting | Pictures

-

A Take On Chiwenga Succession Bid

-

PTUZ slam Mberengwa MP over abuse of office