News

The Khalfan, Zanu PF leaders story: A bond of brotherhood

Published

2 years agoon

By

NewsHawksKAMAL Khalfan, the Honorary Consul of the Sultanate of Oman to Zimbabwe and enterpreneur, who died three days ago at his Harare home, was a larger-than-life character.

Khalfan’s death had a devastating effect on his family, particularly his wife Iryna “Amira” Iefremova and children, especially his young little daughter.

Iryna had a grip on him. A Ukrainian of Russian extraction, she was dominant in the house, but respectful.

She called him Kamal, his first name, not Khalfan despite their huge age difference in marriage, his second.

Khalfan, a liberal Muslim who grew up in Zanzibar, Tanzania, and Oman, and stayed in other countries, including the United Kingdom, Kuwait, Libya, Brazil and then Zimbabwe, was always all smiles when Amira brought food and drinks for him and friends.

Amira was always chatty, cheerful and confident, even on bad days. She was kind even to her maids.

She never showed attitude or emotions when dealing with unpleasant situations among people. Khalfan narrated how he met Amira, but it is a story for another day, except that they were very close as a couple and always enjoyed each other’s company.

As a newcomer to Zimbabwe in 1980 who wanted a new environment and chasing the proverbial greener pastures outside his familiar East African environs and Oman, Khalfan influenced Zanu PF leaders more than any single outsider would dream of doing in his 44-odd years in the country.

That is why his story matters.

Khalfan’s body was flown to his home country Oman for burial in Muscat, the nation’s capital, where he took several Zanu PF leaders for visits over the years.

He expressed his wish to be buried in Oman when he was still alive.

Khalfan had a huge seaside mansion in Muscat, which he was proud of so much.

To his family, relatives and friends, it is surreal that he is gone. His death was totally unexpected.

Only on Tuesday he had an interview and was in high spirits.

Having arrived in Zimbabwe from Zanzibar 44 years ago — in 1980 — Khalfan became close to top Zanu PF politicians, including former president Robert Mugabe, his late wife Sally and later Grace, President Emmerson Mnangagwa, Sydney Sekeramayi, Constantino Chiwenga, Solomon Mujuru, Obert Mpofu (from the Harare International Airport where he worked), a number of ministers, and later young generation political elites such as Saviour Kasukuwere and Walter Mzembi, among others.

Khalfan had a lot in common with Zanu PF leaders: He had lived in an independent African country where they had also operated from — Tanzania; for he spoke Swahili like some of them did (he called this author Bwana, meaning sir/boss in Swahili), he understood Africa’s liberation struggles, politics and post-colonial dynamics, especially given that he had close friends in high places in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda.

His networks in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda were as equally deep as those in Zimbabwe.

But he loved Zimbabwe more, although he was shaken by the brutality and violence of its politics and leaders. He really never understood why. But Khalfan understood post-colonial Africa; that is, what happens after the liberation movements had taken over. He had been there before.

Tanzania was a case study for him.

He was not all that filfty rich, but had old money, both inherited and worked for. Khalfan had a hawk eye for business opportunities.

As result, many Zanu PF leaders learnt how to do business and how it works from him, particularly Mujuru and Mnangagwa. He knew most senior Zanu PF leaders’ business deals, their ways of making money or failing to do the same and their liabilities, including their corrupt activities. He established Catercraft as a partnership with Zanu PF, and other critical ventures.

Khalfan was involved in some diamond mining deals in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with Mnangagwa, the army and his native Omani friend Thamer Said Ahmed Al Shanfari.

But it did not end well with Shanfari, a wily and crafty operator who left Zimbabwe on the run in 2012.

This followed a raid at his house, number 57 Follyjon Crescent, Glen Lorne, Harare, by a security crack unit drawn from police, immigration, Central Intelligence Organisation and the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority in 2012.

The swoop on the house — owned by Shanfari, the former chairperson of Cayman Islands-based mining company Oryx Natural Resources (ONR) — on 3 January 2012 led to the arrest of a Russian national Alexander Filegon alias Alexander Filatov, and an Israeli, Mike Raslan, who were diamond dealers. Filegon and Raslan were later deported.

It was during that raid at number 57 Follyjon — a popular rendezvous for dealers frequented by Zanu PF ministers and politburo members — that Didymus Mutasa and a fellow minister were caught up there.

In 2008, Shanfari was put on the United States government sanctions list due to his links to Mugabe and ONR, but he issued a statement denying the links and said he resigned from the company in 2002.

Shanfari was also mentioned in a report produced by a United Nations panel of experts titled the “Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of Congo”, dated 8 October 2002.

This author was one of the Zimbabweans interviewed by the UN during the study as he wrote stories about the DRC and the scramble for diamonds there.

The report said ONR represented covert Zimbabwean military financial interests in negotiations with state mining companies in the DRC.

It also said ONR and Shanfari were engaged in illegal trafficking of blood diamonds from DRC and were financing Zanu PF stolen elections.

The surprise raid at the Glen Lorne house was led by a senior immigration official, Evans Siziba, after whistleblowers revealed Filegon and Raslan were dealing in diamonds and had stashed US$400 000 at the premises on the day, while trading in illegal diamonds and gold.

Evans Siziba is brother to the late Chemist Siziba, a pioneering indigenous telecoms businessman.

The story of the raid on diamond dealers was first exposed by the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper run by current NewsHawks editors at the time.

Khalfan and Shanfari were deeply involved in DRC diamond deals, although the former always said they lost and not made money in the Congo jungles.

Various reports at the time, including a UN investigation, said Khalfan was involved in a diamond mining deal in Mbuji-Mayi with Mnangagwa and Shanfari through ONR. That deal damaged Khalfan’s reputation, together with those of Mnangagwa and Shanfari.

Zimbabwean army commanders involved in the Congo war were also entangled in the looting spree.

It all began with a proposal that the late president Laurent Kabila of the Congo made to Mugabe in 1998 as he faced removal by rebel forces.

Facing heavy military pressure from rebel armies backed by Uganda and Rwanda, Kabila proposed to Mugabe that he would give him access to a diamond concession in the Congo valued at US$1 billion — located in Mbuji-Mayi — in exchange for the loan of his army.

Other big Zimbabwean businessmen, for instance Billy Rautenbach and the late John Bredenkamp, were also involved in the fortune-hunting.

Mugabe then rod roughshod over the Soithern African Development Community to send troops to the DRC for political, prestige and financial reasons in the personal and national interest.

Geopolitics and regional brotherhood were the framework of the intervention. Kabila’s son Joseph, who succeeded him after the assassination in January 2001, at some point demanded US$1 billion from Zimbabwe, saying it had looted the DRC.

That money was never paid.

Harare argued that the war cost it lives, equipment and economic value way more than US$1 billion.

Initially, Mugabe had readily agreed to the diamonds-for-soldiers deal, but what he did not have was technical or commercial expertise to extract the diamonds.

Enter Khalfan, an Oryx shareholder and a connected Harare resident who rejoiced in his title as honorary consul of Oman in Zimbabwe and hunting opportunities.

Western media claimed he was an arms dealer, but he denied that vehemently.

Khalfan received bad publicity from the media in Zimbabwe and overseas on different issues.

He sued some media organisations and won in other cases, including against big Western media groups.

The BBC was also sued in one of the big cases and apologised for linking Oryx to Al Qaeda, Osama bin Laden’s terrorist group. However, his headache in media was against the Daily News under Stanley Gama’s editorship.

In January 2014, the paper reported that a series of e-mails between Khalfan and French-based German investor Dietrich Herzog, who was swindled US$3 million in Zimbabwe allegedly by Shanfari, had revealed money laundering and gay activities.

The report dragged in some names of top government officials, alleging corruption.

Khalfan sued the Daily News for US$10 million over some of the stories, with the newspaper responding by filing an appearance to defend.

Khalfan said the Daily News had badly damaged his reputation by publishing the “false” stories.

But Gama and his reporter Fungai Kwaramba stood by their stories.

Khalfan was convinced the articles were sponsored by Shanfari.

In anger, Khalfan tried to nail Gama and the reporter through criminal defamation, but he lost as the law had been struck off the statutes by the constitutional court a year earlier. It is strange some Zimbabwean lawyers are still not aware of that to this day, 10 years on.

The NewsHawks has been sued in the past for criminal defamation based on the law which no longer exists, just like Job Sikhala, Fadzayi Mahere and Hopewell Chin’ono were.

Khalfan was so hurt by the reports. He did everything to fight that, but Gama and his team stood firm.

At some point during the bruising battle, Khalfan was prepared for an out-of-court settlement.

An editor of a local weekly whose paper had reported on the raid on Shanfari and others was engaged to mediate between friends.

Khalfan’s approach was to talk to the Johannesburg-based Daily News owner Jethro Goko to resolve the situation.

Since the local editor who was the mediator had worked with Goko before at the Business Day in South Africa as its Zimbabwean correspondent under Peter Bruce’s editorship, he was most suitable to help resolve the situation.

Khalfan was worried about the allegations of corruption and homosexuality, things which are not tolerated in his home country, a Muslim and Arabian nation.

Oman rulers got involved in the issue and pressured him to resolve the issue or relinquish the honorary diplomatic post. Yet amid the storm, Khalfan would say: “I can face corruption allegations and win, but that I’m gay is ridiculous — I mean how can I be accused of that? My wife would be very happy to hear that. I hope she is reading the stories.

If anything, she thinks I’m a womaniser, so this story confuses her and on that score it’s very helpful.

The Daily News is doing a good job on that!” Gama and Khalfan later met at his home via the mediator, but the case was never properly resolved, although tensions subsequently subsided.

The Daily News did well to resist Khalfan’s pressure — he had the backing of top Zanu PF and government officials, except Jonathan Moyo, back then as minister of Information, who denounced Daily News journalists’ arrest on the case.

Yet Khalfan also had a right to fight back because of the serious nature of the allegations, particularly that he was gay, which the publication could not prove.

The mediator insisted that no-one would win that fierce battle, thus an amicable resolution was indispensable and urgently needed.

While all that was happening, Shanfari had escaped Zimbabwe with an Israeli model into Oman, which Khalfan took advantage of to brew problems for him back home. Shanfari bringing an Israeli girlfriend into an Arab and Muslim country surely was hostage to fortune for Khalfan.

It is hard for Arabian authorities to trust an Israeli.

Shanfari ran into a challenge over that.

He tried to sue journalists from the Middle East and London, but his threats were resisted as the story was true, thus could not be defamatory.

Truth — together with facts and the public interest — is the best line of defence in defamation lawsuits.

Meanwhile, Khalfan was responsible for bringing Shanfari to Zimbabwe in the first place for diamonds investment in the DRC. Shanfari, a 34-year-old graduate of the Colorado School of Mines then, and who came from a very wealthy and influential Omani family, flew to Harare to meet Mugabe to start diamond mining amid a scramble in the DRC.

According to the UN report, a company called Sengamines was created, a joint venture between Shanfari’s Oryx, Osleg (the business wing of the Zimbabwean armed forces) and a third co-signatory to the agreement, dated 16 July 1999.

Osleg had a partnership agreement with Congo’s Comiex, a private company linked to Kabila.

It is difficult to imagine a rasher choice of business partners for a company which cared about its reputation.

When UN experts talked about Zimbabwe, contacts in Washington and London — in congress or the state department, or pentagon, or foreign office, or House of Lords — the words that kept recurring were “mafia”, “pillage” and “criminal”. Khalfan did not like that. He denied, denied and denied everything!

The consensus, summed up by one congressional staffer in Washington, was that the Zimbabwean government is “a criminal organisation run for the benefit of Mugabe and his cronies”.

“Mugabe always was power-hungry, but not, I thought, corrupt. I never imagined he would end up presiding over the most corrupt regime in Africa,” said Robin Renwick, one of the chief architects of the Lancaster House agreement, which gave independence to Zimbabwe and, as it turned out, uninterrupted power to Mugabe and his Zanu PF.

Renwick, later the British ambassador in South Africa and Washington, was one of the vocal proponents of the European Union visa ban and assets freeze that were imposed that year on Mugabe and 71 of his associates.

Russ Feingold, the Democrat who chairs the US senate’s sub-committee on Africa, had pushed for similar sanctions in Washington.

Senator Feingold, who had met with members of Mugabe’s inner circle, said Zimbabwe’s “elite” had “strong incentives to retain power, regardless of the cost to the country”, and it was difficult to avoid the conclusion “that public office is being used almost solely for private gain”.

Or, as Renwick more bluntly put it: “The Zimbabwean army has been rented out in the Congo for the benefit of Mugabe and the mafia around him.”

Yet after that Khalfan survived the storm; unscathed.

His biggest strength was avoiding local Zimbabwean politics and refusing to be partisan.

Whenever Zanu PF leaders plunged into political power struggles and fights, he remained neutral to maintain access and serve his interests in the process.

In that sense, he was a unifier and a strategic thinker.

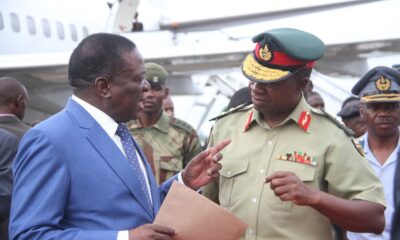

That is why Mnangagwa went to his home on Thursday night for mourning with his two deputies and other top party leaders, a group of uneasy Zanu PF bedfellows.

Mnangagwa was close to the deceased. Khalfan always told a fascinating story about his relationship with Mnangagwa. They first met in 1980 when he visited the newly independent country to explore new opportunities.

Zimbabwe was the most industrialised sub-Saharan African country outside South Africa before it was destroyed by Mugabe and his corrupt and incompetent regime.

Khalfan became friends with Mnangagwa and Sekeramayi who persuaded him to relocate to Zimbabwe.

So one day when Khalfan had already settled in Zimbabwe, Mnangagwa borrowed his sports car which he had imported from the United Kingdom where he had lived sometime back.

So the car’s speedometer was in miles. Mnangagwa got into the car and started driving down during the night to Kwekwe, his political stronghold.

He was racing Schumacher-style and zapping past other cars on the road like Lewis Hamilton on a Formula 1 track. Mnangagwa was driving at 120 miles an hour, without realising it meant 193km.

At some bend he lost control and tried to brake for 100 metres, eventually falling into a ditch.

Khalfan was called and when we arrived at the scene of the accident, he was shocked by what he saw, but still asked Mnangagwa what his speed was before he crashed.

Mnangagwa replied 120km; and Khalfan said “no these are miles, so you were close to 200km an hour — dangerous”. Mnangagwa retold the story in front of mourners, senior government and Zanu PF officials, including Sekeramayi, on Thursday night, with his arm over the tender shoulders of Khalfan’s widow.

He said that some white farmers were woken up by the loud bang of the car crash and they went out to investigate using torches.

When they got to the scene, they were busy admiring the car saying it was nice, to which Mnangagwa angrily replied describing them “stupid” as they appeared more worried about the car than his life. Apart from Zimbabwe, Khalfan had a vast network of contacts in the region and elsewhere.

He knew ANC top figures in South Africa, especially those who were at some point based in Zambia and Tanzania.

Apart from political elites, Khalfan also had friends in the business community, professional circles and the media.

He was involved in charity work, for instance he was patron of the army charity and organised horse-racing events.

Khalfan was chairperson of the board of trustees of the Republic Cup, a horse-racing competition.

Although at the beginning he was close to Mnangagwa and Sekeramayi, he later became Chiwenga’s friend as well.

Always easy-going, Khalfan maintained friendships with rival Zanu PF leaders throughout the turbulent Mugabe years, before and after the 2017 coup, which he privately described as a “dramatic power shift”.

This was more like what Lord Peter Hain, a former MP for Neath, British minister and anti-apartheid activist, told a local journalist in an interview at the Meikles Hotel (now the Hyatt Regency) soon after the coup.

Hain had come from seeing Mnangagwa over business issues the previous night at the time.

Whenever Zanu PF’s internal power struggles were discussed, Khalfan would not take sides, except remarking that politicians don’t seem to realise that they need each other.

In a recent private conversation over the Mnangagwa-Chiwenga power struggle, Khalfan remarked: “Look, for stability these guys need each other; Mnangagwa is a politician, he commands votes, but but then Chiwenga is a military figure, he commands the gun. The current unstable power structure in Zanu PF and Zimbabwe needs a balance between that.

“Continued fragmentation and divisions won’t help Zanu PF eventually. I think the situation is just too fragile.”

However, beyond such observations Khalfan consciously avoided meddling in Zimbabwean politics, saying “I’m not involved in politics”.

He would also refuse to take sides in discussions be they on Zanu PF, the opposition or elections.

Yet it stands to reason that he preferred his friends won elections all time for him to maintain his privileges and protection. Deep down Khalfan loved Zimbabwe.

That is why he spent 44 years in the country until his death on Wednesday night when he could have gone to live somewhere else.

Khalfan was mostly at his happiest sitting around his home bar at his vast Chisipite mansion quaffing whisky and cracking jokes.

He had a great sense of humour.

In fact, he was unable to engage without jokes.

He was also at his most comfy at his alluring farm in Macheke, Mashonaland East province.

Khalfan’s farm, which he bought in the 1980s, is an aesthetically attention-grabbing landscape.

Nestled at the heart of the countryside, the farm stretches across hilly terrain and lush green pastures, where wildflowers bloom in every colour of the rainbow.

A tranquil pond glimmers in the distance, home to a family of a variety of wildlife and cattle.

It has farmland and a game reserve full of antelopes varying significantly in sizes — sable antelope, kudu, impala, topi, wildebeest and gazelle, among other wildlife. There were some rhinos that always grazed around the main farm entrance.

Khalfan would sometimes take friends, including Chiwenga, for hunting there, particularly for the impala which are there in large numbers.

Poachers were his nightmare as a result. Cattle roam freely, their skins glistening in the sunlight as they graze on the sweet grass.

Tobacco crops stand tall and proud, their broad leaves rustling gently in the breeze. During the farming season, the air around the farm is filled with aromatic scents of blooming tobacco flowers, attracting a flurry of butterflies and bees.

As you wander through the farm, sounds of nature engulf you — birds melodiously singing in the trees, the soft lowing of cattle, and the gentle rustle of leaves. Wildlife gazing and huddling together in jittery postures, while making occasional panicky and disorderly dashes, staring, ears trained for attention and fearing the unknown.

The rolling hilly outcrops stretch out as far as the eye could see in the distant horizon, a picturesque landscape of natural beauty and tranquility.

In there is a big dam which majestically stretches across the heart of the farm.

On the dam’s stunning shores lies an imposing double-storey mansion which makes the surroundings look scenic.

It seems Khalfan had a thing for double storeys; his mansions in Harare, at the farm and in Muscat are all double-storeys. A rustic barn stands sentinel, weathered wooden boards bearing witness to generations of farming tradition.

Khalfan’s farm was a haven of peace and serenity, where nature and humanity coexist in perfect harmony.

In the region, Khalfan also had close friends in high places.

For instance, he was very close to the late former Zambian president Rupiah Banda. Banda was born in 1937 and grew up in Gwanda, Zimbabwe, to Zambian immigrant parents.

He was educated in Zimbabwe and Zambia with the help of his parents, the Dutch Reformed Church and the Naik family, prominent Gwanda political activists who supported the Zimbabwean liberation struggle.

Banda spoke fluent Ndebele and married a Zimbabwean woman, Thandiwe, as his second wife. His first wife was Hope Mwansa Makulu. She died in 2000.

When he officially opened the Zimbabwe International Trade Fair in Bulawayo in 2009 during Mugabe’s era, Banda spoke to people in Ndebele.

People joked in Matabeleland that Banda was the “first Ndebele-speaking president” in the region.

Banda also visited Gwanda, his place of birth. It was a homecoming trip. Sentimental and emotional for him. He went to a nearby mine where his parents worked and a tree in Jahunda Township where he played as a young boy.

There are many prominent Zimbabweans of Zambian, Malawian and Mozambican descent in high places today. Immigrants influenced Zimbabwean politics, business, music, sports and other endeavours in a big way.

It is difficult to discuss Zimbabwean music and football without mentioning immigrants.

Khalfan liked Banda a lot and when he died in March 2022, he travelled to Zambia for his funeral.

Mnangagwa, who also revered Banda, and Sekeramayi attended the funeral as well. At the funeral, Mnangagwa remarked on an interesting irony; Banda was born and bred in Zimbabwe, then became Zambian president later in life.

Yet himself, Mnangagwa, was brought up in Zambia (some say he is Zambian), but became Zimbabwean president.

They were also in Unip party under Kenneth Kaunda at one point.

Khalfan’s life crossed paths with Banda and Sekeramayi differently before they converged later.

By the time Khalfan met Banda, the late Zambian president had already known Sekeramayi whom he helped move from Czechslovakia to Lund University in Sweden in 1964 to study medicine on a scholarship.

Sekeramayi later joined the struggle from overseas.

Banda was the international secretary of the Zambia Students’ Union then and had contacts. He helped many students go abroad.

Khalfan was part of the funeral at which President Hakainde Hichilema led hundreds of mourners, including foreign leaders, in paying homage to the former president who died in 2022 aged 85 after battling colon cancer since 2020.

Khalfan was originally from Oman, a small oil-producing Middle Eastern country occupying the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula at the confluence of the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea, but grew up in Zanzibar.

Oman’s oil reserves primarily consist of heavy crude, and China is the predominant export market.

In the 19th century, Zanzibar once became the capital of Oman.

Khalfan always visited Oman and liked basking in the sun around his seaside mansion.

From Harare, he would travel to Dubai — a favourite destination of his and spend days there — and then to Muscat. Mnangagwa told mourners on Thursday night: “We received the news of the death of our dear brother Kamal Khalfan with deep sorrow. It was so sudden. We never heard of him being ill.

“I met Kamal in 1980 and he was resident in Zanzibar. He then came over on a visit and met me and Cde Sekeramayi and we became friends.

“He then saw that this country was beautiful and decided to stay. He has been here for 44 years, and in those 44 years he has been our brother. Today, as we were travelling to Victoria Falls, the First Lady phoned me and said your brother has passed on. She said I am told he passed on in his sleep”.

Khalfan may be gone, but his legacy as a businessman, charity patron and enabler in politics, business and community circles remains.

He made an indelible mark — with the good and the bad — on Zimbabwean society with a big footprint across its various spheres of life.— The NewsHawks.

You may like