Opinion

Repression and recession in a volatile,

crisis-ridden and broken Zimbabwe

Published

5 years agoon

By

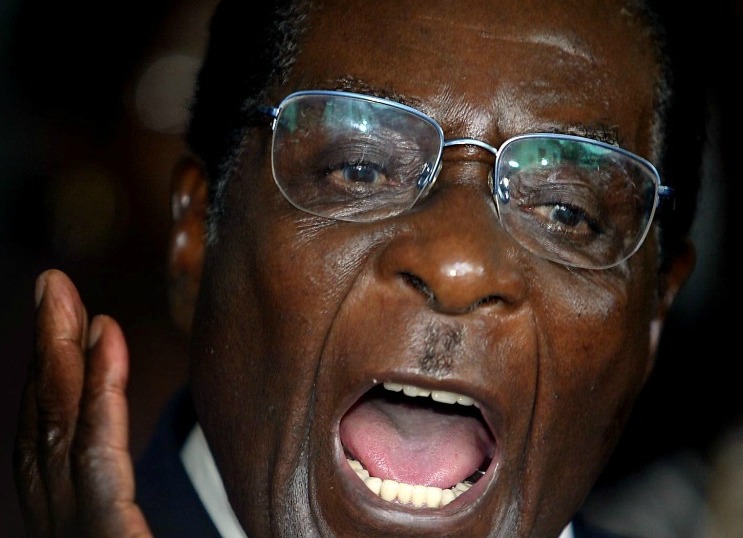

NewsHawksTHREE years after a coup ended Robert Mugabe’s rule, the situation in Zimbabwe has gone from bad to worse, as political tensions mount, the economy falls apart and the population faces hunger and COVID-19.

Having signalled a desire to stabilise the economy and ease repression, President Emmerson Mnangagwa has disappointed. The state is arresting opponents who protest government corruption and incompetence.

Meanwhile, government-allied businessmen are tightening their grip on what is left of the economy, while citizens cope with austerity measures and soaring inflation. Violence and lawlessness are on the rise.

Fearing major unrest, or even another coup sparked by ruling-party divisions, Zimbabwe’s most important neighbour, South Africa, is ditching its tolerant posture toward Harare.

It should go further, pushing Mnangagwa to roll back repression and begin dialogue with the opposition on economic reform. Pretoria could meanwhile work out reform benchmarks with Western governments, which would be guideposts for when to support the lifting of sanctions and extend debt relief for Zimbabwe.

South Africa has been a key mediator in Zimbabwe’s political crises for years. In 2008, it brokered a national unity government in the country following international outrage at violence that followed Mugabe’s refusal to accept his first-round election defeat by Morgan Tsvangirai, then the opposition leader.

The deal, midwifed by former South African President Thabo Mbeki, was celebrated by South African officials at the time as vindication of Pretoria’s “quiet diplomacy” with Mugabe, whom South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) still viewed as a liberation icon.

But it infuriated many Zimbabweans, who saw the policy as appeasing a repressive strongman.

Moreover, despite its economic and diplomatic clout with Zimbabwe, and its role as a guarantor of the 2008 agreement, South Africa failed to hold Mugabe to his promises when Zimbabwe’s ruling African National Union Patriotic Front (Zanu PF) flouted the unity accord, allowing Mugabe to consolidate power and win re-election in 2013.

He proceeded to rule unchallenged until the November 2017 coup.

Three years after Mugabe’s ouster, Zanu PF clings to power under Mnangagwa. Following the 2018 election, contested as fraudulent by the Movement for Democratic Change-Alliance (MDC-A) opposition party, Zimbabwe’s government has stepped up repression amid an economic freefall and mounting social problems in a way that could propel the country toward renewed conflict.

Beyond arresting its opponents, it accuses them of promoting a violent regime change agenda at the behest of foreign interests.

Moreover, despite Mnangagwa’s promise of sweeping economic reforms, Zanu PF elites and some of their military allies have cornered much of the economy, profiting handsomely while ordinary Zimbabweans face public spending cuts, skyrocketing prices and the COVID-19 pandemic.

As socio-economic tensions rise, so, too, has violent crime, with street gangs increasingly prevalent, some of them co-opted by rival Zanu PF factions at a time when ruling-party unity is itself coming under strain.

Zimbabwe’s government has stepped up repression amid an economic freefall and mounting social problems in a way that could propel the country toward renewed conflict.

Under Cyril Ramaphosa’s presidency, which began in 2018, the South African government has begun to take more active steps to address the risk that continual cycles of repression and economic failure could deliver a destabilising crisis on its doorstep.

In the last eighteen months, Pretoria has become noticeably more critical of Zanu PF’s mishandling of Zimbabwe’s governance, calling out systemic corruption and capture of state assets by ruling elites in Harare.

But while Pretoria has appointed envoys to travel to Harare to encourage dialogue between Zanu PF and MDC-A, as well as with other political and civil society actors, its efforts have yielded no fruit, in part because authorities in Zimbabwe blocked the emissaries’ attempts to meet opposition leaders.

Without a political compact between Zanu PF and MDC-A, the chances of meaningful reform that could open up the economy, ease political tensions and lead to a roadmap for clean elections down the road will dwindle.

Pretoria should not give up. Ramaphosa’s government should use its influence as Zimbabwe’s most important neighbour and trading partner to keep pressing Harare to dial back repression and to demonstrate commitment to real dialogue with the opposition.

Pretoria must insist that Harare give its envoys space to engage with MDC-A and other opposition and civil society figures so that it can bring them to the table for talks.

It should then push Zanu PF and MDC-A to enter negotiations about how to strengthen the auditing of government finances and tackle high-level corruption, as a first step toward stopping the plunder of state assets by unaccountable elites and resetting economic governance.

Meanwhile, Pretoria should reach out to the US, European Union (EU) and UK and work with them to develop a credible roadmap for reform in Zimbabwe, which could be linked to decisions about lifting sanctions and encouraging international financial institutions to reschedule debt or extend new lines of credit to resuscitate Zimbabwe’s moribund economy.

By arming Pretoria with incentives to motivate Harare, donors can help position it to nudge its neighbour down the long-elusive path toward political and economic reform.

Repression and recession

The ouster of Mugabe in November 2017 raised hopes that Zimbabwe would embark on much-needed reforms to protect political freedoms, end government repression and revitalise an ailing economy.

When Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s long-term ally and one-time vice president, took power after the coup, he promised “radical economic reforms”.

He also stated the country was under a “new dispensation”, raising hopes he would hold free and fair elections and stop systematic abuses of opposition activists and politicians.

But hope swiftly gave way to disappointment as Mnangagwa cracked down on protesters challenging his victory in the 2018 election, which were criticised by foreign observers for being less than free and fair.

Once in office, he fell back on draconian legislation governing public order and media freedoms to muzzle opponents.

As the clampdown continued, the economy also went from bad to worse. Internal Zanu PF divisions also widened amid a slew of government corruption scandals.

Repression and economic woes

Zimbabwe’s crisis has only deepened since the 31 July 2018 presidential election. On 1 August, security forces opened fire on crowds protesting the conduct of the polls, the first time in Zimbabwe’s history that either policemen or soldiers had used live ammunition against peaceful demonstrators.

Six people died. MDC-A rejected Mnangagwa’s narrow election victory, claiming irregularities in vote counting, but the constitutional court dismissed its legal challenge.

MDC-A, which enjoys sizeable support in cities, has continued to refuse to recognise Mnangagwa as the elected president.

It has also boycotted the Political Actors Dialogue, set up by the government in February 2019 in what it said was an effort to bring together political leaders to debate the national crisis.

The opposition party argues that Zanu PF is using the dialogue platform to present itself in a conciliatory light while it continues to treat its opponents brutally.

Amid the political crisis, the country’s economy has nosedived. The government says its major economic reform effort – the Transition Stabilisation Program launched in October 2018 – has delivered macro-economic stability.

But critics have ample reason to dispute this claim, pointing to a currency devaluation crisis, rampant inflation, ballooning unemployment, widespread poverty and pervasive food insecurity.

Government targets of 9% growth for 2019 were wildly optimistic, as the economy in fact contracted by 12.8 per cent.

In February 2020, the International Monetary Fund concluded that its Staff-Monitored Programme, introduced to assist the government with the 2018 Transitional Stabilisation Programme, was “off track” and that there had been an “uneven implementation of reforms, notably delays and missteps in foreign exchange and monetary reforms”.

As the economy collapses, social tensions are mounting, seemingly exacerbated by the stabilisation program.

While sold to the public as a reform package that would stabilise Zimbabwe’s economy and promote foreign investment, the program has not delivered on its key promises, including state-owned enterprise reform, infrastructure development and turning the tide on corruption.

At the same time, it has exacerbated economic hardship for ordinary Zimbabweans.

Painful cuts in public spending have hit public-sector workers hard; many public servants are unable even to afford the commute to work.

Strikes by teachers, nurses and doctors protesting the drop in their purchasing power have taken a toll on the health and education sectors.

A very steep devaluation of the country’s currency also resulted in higher costs for imported goods. As restrictions on the use of foreign exchange have also kicked in and the currency is in a state of collapse, inflation, running at over 600 per cent, has further emptied the pockets of civil servants and other ordinary Zimbabweans.

With political and social tensions mounting, and criminal violence on the rise, the government has continued to use brute force to stamp out dissent.

With political and social tensions mounting, and criminal violence on the rise, the government has continued to use brute force to stamp out dissent.

In January 2019, protests – some of which spilled over into violent looting sprees – erupted across Zimbabwe after the government massively hiked fuel prices.

The subsequent crackdown left thirteen dead and over 1 000 arrested, amid widespread allegations of beatings, abductions, torture and rape by security forces.

According to human rights monitors, state security agents or sub-contracted thugs have subsequently continued to engage in these abuses.

A series of arrests of political opposition, trade union and civil society leaders on charges of subversion and treason followed as the next phase of the crackdown, though none of the charges have stuck in court.

Meanwhile, criminal violence, primarily perpetrated by desperate unemployed men joining machete gangs, is spiking.

The COVID-19 pandemic, beyond exposing the Zimbabwean health system’s endemic failings, has deepened the country’s political and economic crisis.

Lockdown measures taken to fight the disease have hurt the economy. The police and military have also been using coronavirus-related restrictions as a pretext to target opposition members and supporters engaging in peaceful protest for arrest.

In July 2020, authorities clamped down on government critics, including by arresting opposition leader Jacob Ngarivhume for organising protests and by incarcerating Booker Prize-shortlisted writer Tsitsi Dangarembga for attending demonstrations.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reacted with a statement emphasising that Zimbabwe should not use COVID-19 “to clamp down on fundamental freedoms, including freedom of speech and the right to peaceful assembly”.

Western sanctions

Officials in Harare portray the country’s economic crisis as the combined result of drought and sanctions levied by Western governments. They point in particular to measures imposed by the US, as well as by the EU, the UK, Australia and Canada.

These measures range from an arms sales ban to denial of visas to Zimbabwean officials to financial sanctions targeted at individuals and commercial entities designated for their role in corruption and rights abuses.

In addition, the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (ZDERA), passed by the US congress in 2001 and amended in 2018, mandates US authorities to vote against Harare’s access to new lines of credit from international financial institutions until it carries out key governance, electoral and human rights reforms.

Mnangagwa and his supporters portray these sanctions as punishing the Zimbabwean people, saying they have a chilling effect on investors, who avoid the country altogether rather than risk running afoul of them, and have made borrowing on the commercial market unaffordable for banks.

The upshot, the government argues, is that “the average Zimbabwean pays the heaviest price”. Western governments argue that this claim is an exaggeration; they say the sanctions target elite economic actors and maintain that if Zimbabwean banks cannot borrow cheaply, it is a result of poor governance in Harare. U.S. officials also say ZDERA provisions have not come into play, because Zimbabwe’s debt arrears prevent it from obtaining loans from international financial institutions whatever Washington’s position.

Zanu PF divisions

As Zimbabwe falls further into an economic abyss, fractures are also opening in ZANU-PF power circles.

One fault line is between groups loyal to Mnangagwa and those that oppose him, including followers of Constantino Chiwenga, his deputy. Chiwenga is a former army general who led the 2017 coup against Mugabe and is now reportedly positioning himself to challenge for the party leadership ahead of the 2023 elections.

The two factions share the common objective of keeping Zanu PF in office, but the tensions between them are rising.

Evidence of such division is mounting. In July 2020, for example, party spokesman Patrick Chinamasa said Zanu PF had suspended two politburo members after State Security Minister Owen Ncube reported that posters and fliers praising Chiwenga and calling for Mnangagwa’s removal were found in their homes.

Chinamasa also claimed that unnamed external forces were “working with certain individuals in the party’s senior ranks to destabilise internal cohesion”.

Corruption scandals

Amid these tensions, numerous corruption scandals have tarnished top officials, revealing the extent of misgovernance and the limits of Zimbabwe’s institutions in dealing with high-level graft.

While the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission (Zacc), which installed its new chairperson in July 2019, has arrested and charged several ministers and senior officials amid the president’s claims that he is taking a “zero tolerance” approach to corruption, prosecutors have yet to deliver a conviction.

In turn, critics have argued that, despite the Zacc initiative, the president and his allies in the legal system are more interested in using the probes to keep senior ZANU-PF officials in check than in punishing them.

Zacc officials say they choose their targets independently but lack the resources to tackle all the most important cases.

Meanwhile, the Zacc has decided not to investigate Kudakwashe Tagwirei, a businessman close to Mnangagwa and Chiwenga, who benefitted from hundreds of millions of dollars in state pay-outs. Washington has now sanctioned Tagwirei for “public corruption”.

At the same time, the government appears to be using another anti-corruption institution to target those who have exposed alleged corruption elsewhere.

For example, the Special Anti-Corruption Unit, created in 2018 and run by Mnangagwa’s nephew out of the office of the presidency, has reportedly been involved in arrests of individuals who were central to investigations of former Health Minister Obadiah Moyo.

He was arrested in June 2020 following Zacc investigations into his alleged award of a contract for supply of COVID-19 personal protection equipment to a United Arab Emirates company, Drax International, without going to tender.

In July, prominent journalist Hopewell Chin’ono, who is credited with exposing the Drax deal, was arrested on charges of plotting to promote public violence. Chin’ono alleges that the special unit is behind his arrest. The unit has also arrested police officers involved in the Drax investigation.

Pretoria comes knocking

Under the presidencies of Thabo Mbeki (1999-2008) and Jacob Zuma (2009-2018), South Africa maintained a policy of “quiet diplomacy” toward its northern neighbour.

In practice, this policy meant generally abstaining from criticising Zimbabwe’s governance and human rights record.

Pretoria argued that this approach allowed it to build confidence and friendly influence with Harare, but many Zimbabweans criticise the strategy as a form of appeasement.

These criticisms resurfaced when Mnangagwa seized power and Pretoria demurred from labelling Mugabe’s ouster as a “coup”, despite the military’s obvious intervention. South Africa nonetheless maintained its posture well after Cyril Ramaphosa became president in February 2018.

When Zimbabwean security forces opened fire on protesters on 1 August 2018, Pretoria was muted. Later that month, Zimbabwe’s constitutional court dismissed an MDC-A petition contesting the election results, with South Africa endorsing the decision. Pretoria also seemingly turned a blind eye to Harare’s attack on protesters in January 2019.

Nevertheless, South Africa under Ramaphosa has gradually shifted its public stance regarding its neighbour’s crisis, moving toward a more assertive and critical position. “It has taken almost two decades for South Africa to appreciate [that] quiet diplomacy toward Zimbabwe has failed to secure results”, says one South African official.

South Africa under Ramaphosa has gradually shifted its public stance regarding its neighbour’s crisis, moving toward a more assertive and critical position.

The first glimpse of Pretoria’s shifting attitude toward Zimbabwe came during Ramaphosa’s address to the Bi-National Commission in Harare in March 2019. Ramaphosa reflected on South Africa’s own experience with “state capture” – a euphemism for entrenched institutional graft – in a passage that was widely interpreted as a coded signal to Mnangagwa to tackle corruption. Pretoria followed up this veiled message in November 2019 with a much more direct statement.

Foreign Affairs Minister Naledi Pandor argued that Zimbabwe’s economic, political and social problems were inextricably linked, that they needed to be addressed simultaneously and that Harare should convene an inclusive national dialogue to determine how to do it.

The reasons for this shift are partly rooted in Pretoria’s assessment that the status quo in Zimbabwe could be damaging for South Africa, especially if more social unrest leads to more Zimbabwean migrants fleeing into South African territory or another coup sets Zimbabwe on a path to even greater instability.

In addition, Ramaphosa increasingly sees instability in Zimbabwe, the biggest importer of South African goods, as a brake on Pretoria’s plans for economic integration of the Southern African Development Community, especially given that its northern neighbour lies at the region’s geographic centre.

Moreover, even at present levels of unrest, instability is pushing Zimbabwean citizens into South Africa, which feeds internal tensions that sometimes flare in acts of xenophobic violence.

Fearing Zimbabwe’s drift into crisis, Pretoria has stepped up attempts to facilitate a national political agreement that could steer the country off its disastrous trajectory.

In December 2019, Mbeki travelled to Zimbabwe, where he met with President Mnangagwa, MDC-A leader Nelson Chamisa, other opposition leaders and civil society organisations, to explore appetites for an inclusive national dialogue.

His attempt to get Mnangagwa and Chamisa in the same room fizzled, however, and Mbeki did not follow up on his promise to return to Harare, reportedly because Mnangagwa refused to answer his calls.

As relations between Pretoria and Harare soured, the South African ambassador to Zimbabwe, Mphakama Mbete, speaking at a meeting in Harare in February 2020, referred directly to Zimbabwe’s governance problems and how they deter foreign investment.

Many interpreted these remarks as a message to Harare that Pretoria was fed up with quiet diplomacy. Although South Africa subsequently turned to dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, appearing to move concerns about Zimbabwe to the back burner, it did not do so for long. Harare’s clampdowns on prominent critics in July 2020 drew international attention, including from Pretoria.

Worried both about these reports and the prospect that more misgovernance and economic woes could lead to greater instability, Ramaphosa announced on 6 August that he was appointing two special envoys to work with Zimbabwe, dispatching them to Harare.

Mnangagwa, however, forbade these diplomats from meeting with opposition leaders as an ostensible matter of diplomatic protocol – a demand that appeared intended to kill any prospect of South African mediation between Zanu PF and the opposition. The envoys have yet to make a subsequent visit to Harare.

Meanwhile, the ANC – which in addition to being South Africa’s ruling party is a member of the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa, to which Zanu PF also belongs – likewise changed its stance toward Zimbabwe’s crisis.

On 31 August, the ANC’s National Executive Committee adopted a resolution welcoming the South African government’s initiatives to press Harare and highlighting the importance of engaging with all parties in Zimbabwe in order to help address the country’s problems.

It was a major step for the ANC to break with liberation movement solidarity by raising its concerns publicly, and the Zanu PF leadership appears to have been both irritated and alarmed. Zanu PF quickly invited the ANC to Zimbabwe in an apparent attempt to influence the party’s agenda and narrative.

An ANC delegation visited on 9 September, but like Ramaphosa’s envoys, it did not meet with any actors from the opposition or civil society.

Nudging Zim toward stability

Pretoria’s move away from its traditional practice of addressing Harare’s transgressions through “quiet diplomacy”, together with the ANC’s endorsement of the pivot, puts South Africa in a position to exert pressure on Zimbabwe’s political leaders to ease repression and draw up a consensual roadmap to address the country’s socio-economic woes.

South Africa and the ANC should thus maintain pressure on the government to enter talks with the opposition and civil society to review possible economic reforms.

Given the entrenched corruption at the top of the Zanu PF government that risks sinking the country, it is clear that only a broader-based ruling coalition can create the kind of foundation for good governance that the country needs. South Africa and the ANC should thus maintain pressure on the government to enter talks with the opposition and civil society to review possible economic reforms that keep front and centre the interests of Zimbabwe’s people and not just its ruling party.

Ideally, these talks would lead to an agreement to enhance controls on public finance as an initial measure to improve governance and help stabilise the economy and prepare the ground for broad-gauge measures.

In public, Mnangagwa and MDC-A leader Chamisa acknowledge the deep corruption in both government and MDC-A-run councils and the pernicious effect such graft has on the country. Any future agreement between them on tackling misgovernance will, however, require a properly resourced Auditor General’s Office with an independent staff who can assess the balance sheets and ownership structures of state-owned companies and examine all government and municipal accounts and state monetary operations.

The Zacc, which has already shown an appetite for going after top Zanu PF officials for corruption, should be given exclusive agency in all national corruption cases as well as more resources and independence so that it can resist any political interference, including pressure to target civil society activists and journalists exposing corruption.

To create the conditions for a dialogue that could lead to these agreements, however, South Africa will have to press Harare to begin rolling back its repression of the government’s opponents, including by taking some visible confidence building steps such as liberating political prisoners.

Pretoria should also request that its envoys have the freedom to operate and meet who they need to in Zimbabwe so that it can start building bridges between rival parties. South Africa should actively lobby other neighbours to join it by appealing to their mutual interest in regional stability.

To ensure that it is not a lonely voice, South Africa should actively lobby other neighbours to join it by appealing to their mutual interest in regional stability. Notably, it should approach Namibia and Angola, two countries with strong diplomatic ties with Zimbabwe and whose ruling parties also belong to the liberation movements’ bloc, in order to persuade them to apply their own pressure on Harare.

The ANC should play a part in this initiative. South Africa should also look to the African Union (AU) for assistance, if possible before Ramaphosa steps down as chair at the end of 2020.

It should request that the AU appoint a high-level mission composed of former heads of state who would travel to Zimbabwe to encourage the government to make progress on political dialogue, governance, human rights and economic recovery plans.

Leaving aside such pressure tactics, South Africa should offer carrots in return for Zanu PF’s cooperation.

Pretoria should offer itself to Harare as an interlocutor in getting Western sanctions lifted and lobbying for international debt relief or access to more lending. South Africa has long maintained that sanctions against Zimbabwe are unjust, and it continues to do so even if it has increasingly expressed misgivings about Zimbabwe’s economic performance.

In order to play the go-between, it will first need to work with Western governments to develop a set of benchmarks that, once achieved, would set the stage for rolling back sanctions as well as supporting international financial institutions in considering rescheduling the US$1.8 billion of debt arrears owed to them and extending concessionary loans to reboot Zimbabwe’s economy.

Working through a South African government that can mobilise regional pressure on Harare may be a more effective way for Western governments estranged from Zanu PF to achieve their aims for better governance in Zimbabwe.

Conclusion

South Africa should have every incentive to help its neighbour Zimbabwe avoid tipping into collapse. Having favoured quiet diplomacy for decades, Pretoria has now adopted a much more critical stance toward Zimbabwe’s failures of governance.

It has also taken the first steps toward coaxing Harare into convening a national dialogue, ending political repression and embarking on meaningful economic reforms.

These steps have had limited effect, however, as Harare continues to block South African efforts to engage with Zimbabwe’s opposition figures and bring them into the same room with their Zanu PF counterparts for meaningful dialogue.

Pretoria should not give up. It should work with Western donors on a roadmap for reforms that could lead to sanctions and debt relief. It should also help Harare see the importance of finally embarking on this long overdue journey. The alternative to reform is likely to be more instability in Zimbabwe and quite possibly in the region.

– International Crisis Group

You may like