Opinion

Politics of appointing a chief justice — from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe

Published

5 years agoon

By

NewsHawksTERERAI MAFUKIDZE

Beginning this week, The NewsHawks will publish a series of articles written by Johannesburg-based Zimbabwean lawyer Tererai Mafukidze about the history and politics, as well as the dynamics of appointing a chief justice in Zimbabwe, tracing the genesis of the issue back to 1927, five years after Southern Rhodesia rejected in a referendum joining the South African Union, when the first head of the judiciary was installed.

Voters had to choose between establishing self-government, joining the Union of South Africa or continuing under the British South Africa Company (BSAC). The BSAC had governed Southern Rhodesia since October 1889 when it was granted a mining exploration charter by the British government.

Its founder, Cecil John Rhodes, was given permission to explore the area north of the Transvaal with unlimited powers. After its pioneer column invaded the country through Tuli in Matabeleland South in 1890, the BSAC founded the town of Salisbury (now Harare) and named the territory Rhodesia in honour of Rhodes. From 1890, the company operated as the government of Southern Rhodesia until 1923.

The first judicial officer to be known by the title chief justice in Zimbabwe was only appointed in 1927. For the first 37 years of colonial rule that position did not exist — at least not by that name.

However, if one were to loosely apply the term chief justice to the person who heads the judiciary, it would be accurate to say that the medical doctor, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, Cecil John Rhodes’s best friend, was the first. Since this ominous beginning, the position of chief justice has remained deeply a matter which attracts huge political and public interest.

The is the third pillar of the government and it is critical in a democracy. Its function and responsibility is to interpret and apply the laws in specific cases and settle disputes. The real meaning of law is what the judges decide during the course of their work.

In a constitutional democracy where the power of the executive is limited by checks and balances, the judiciary is critical because it protects the constitution and guards against executive and legislative and excesses. Role of judiciary as the guardian-protector of the constitution and fundamental rights of the people makes it more critical and of huge public interest.

This is despite that the judiciary is considered the weakest organ of the state as it neither commands an army nor controls the budget. It depends for its influence on enjoying public confidence which gives it moral suasion that forces citizens and other arms of the state to respect and implement its decisions. Its central responsibility is to resolve disputes which arise and to try criminals. Most of its work is not controversial and goes without much public notice.

It is when the judiciary decides constitutional, political and electoral disputes that its role in the state becomes contested terrain. This is because such disputes have far-reaching consequences beyond the litigants concerned. In other words, its decisions in such matters affect all citizens, their future and the nation’s fate.

Any political interest in power wants to control the judiciary. Politicians prefer a supine judiciary when it comes to handling controversial matters. It is in this regard that the judiciary is contested terrain in any polity. Some of the contestations are held quietly, while others are fought in pitched battles between political rivals.

Judicial appointments are in many parts of the world, sadly, political. Zimbabwe is no exception. Not every appointment though raises political interest or concerns.

However, the appointment of the chief justice, who is the head of the judiciary, is frequently a decision based on political considerations. This is why political leaders want to influence the decision as much as possible. It has political implications, sometimes serious.

The chief justice is considered the first amongst equals – just like a prime minister.

Three years ago, the supreme court of India had to decide a matter in which the litigants challenged the role of the chief justice of India and demanded the publication of the guidelines and framework for rational and transparent allocation of cases and constitution of benches to hear cases.

The court said that since the chief justice of India is a high constitutional functionary, there cannot be any distrust about the responsibilities he discharges to ensure that the supreme court carries out the work required under the constitution.

The case arose after a press conference was held by some of the senior-most supreme court judges in an unprecedented event where they alleged improper allocation of cases by the chief justice.

As will emerge from later discussions on the historical role of the chief justice in Zimbabwe, the ability to allocate cases and set up benches to hear cases can be used to undermine judicial independence, pander to political whim and for corruption.

No sooner had Zimbabweans decided in 2013 in a new constitution that the appointment of the head of the judiciary, like that of other judges, should be subject to a competitive and transparent interview process than voters witnessed an immediate push to amend the freshly-minted constitution to give the President the power to choose the chief justice, the deputy chief justice and the judge president of the High Court.

That is under Zimbabwe Constitutional Amendment (No.1) passed by Senate on 6 April. It now awaits presidential assent. Constitutional Amendment (No.2), passed by the National Assembly on 20 April and which expands power of the President, gives him more power to appoint other judges in consultation with the Judicial Service Commission, discarding the public, open and transparent process based on interviews.

The legal pitfall that befell the amendment was salvaged through an order issued by the Constitutional Court, which is bizarre to the extent that in a February 2021 judgment, one of the judges has admitted that the order of the court to revive a Bill and place it before a new Senate was itself without legal foundation.

In fact, two judges, Annie-Marie Gowora and Bharat Patel, pointed out serious flaws in the process.

The swift amendment was intended to return the direct power of appointment to the President. That alone tells us why the debate about whether current Chief Justice Luke Malaba should stay or retire remains largely a political question.

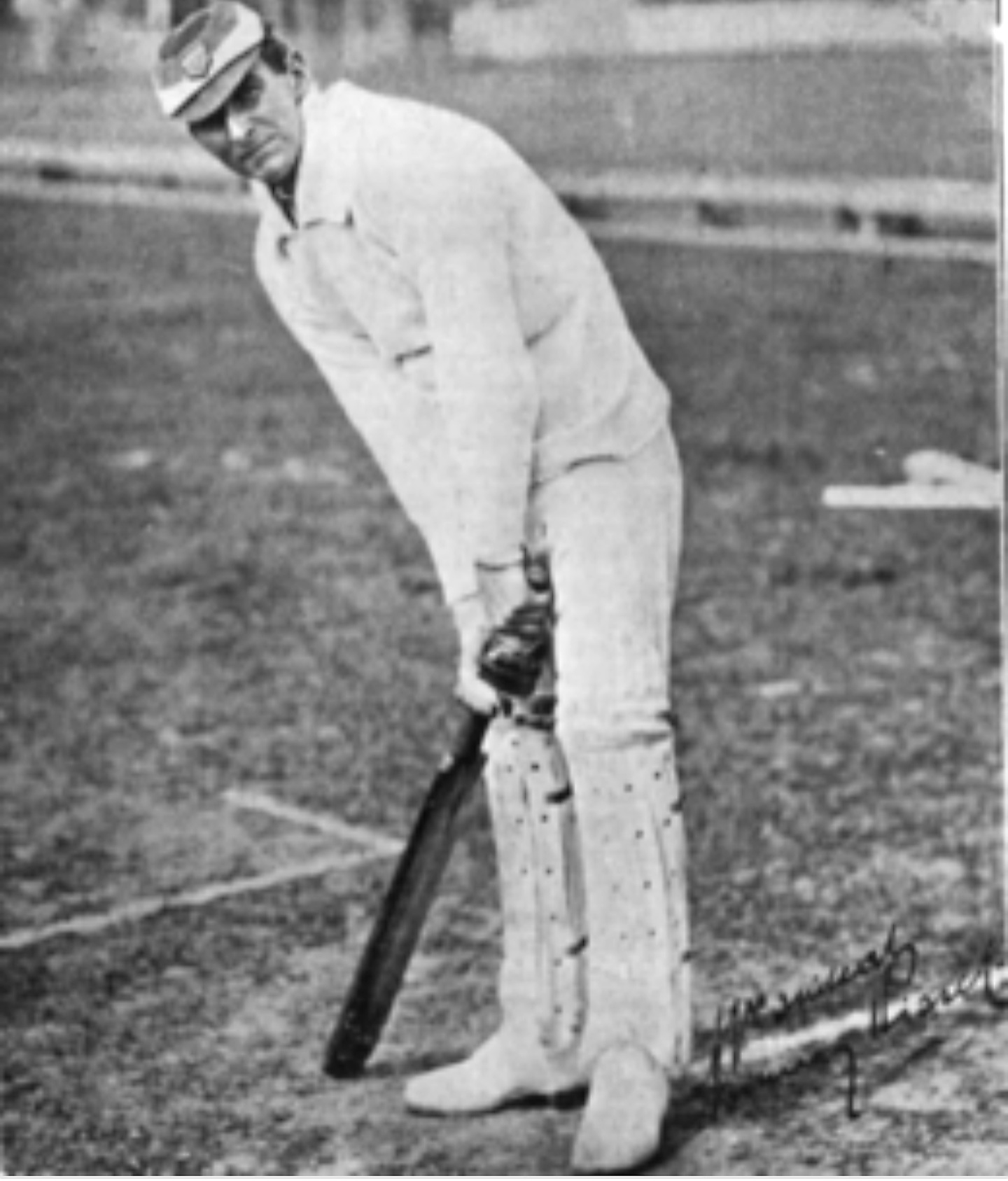

The choice of chief justice — from Sir Murray Bisset (pictured) to Malaba — or should it be from chief magistrate Jameson, has been deeply a political question.

Bisset (14 April 1876 – 24 October 1931) was a Test cricketer who captained South Africa before moving go Southern Rhodesia where he served as chief justice and briefly as the country’s governor.

Born in Port Elizabeth, Bisset was the fifth son of James Bisset, former mayor of Wynberg, and Emily, née Jarvis, daughter of Hercules Jarvis, former mayor of Cape Town.

The first European judiciary

In 1890, Zimbabwe was conquered by the BSAC which operated under a Royal Charter granted by the British monarchy to Rhodes’s company. As soon as the BSAC established some rudimentary administration, the company’s first administrator of Mashonaland, A.R. Colquhoun, decreed through proclamation No.1 of 28 September 1890 that the laws of the Cape Colony (South Africa) were to be applicable in the new territory.

The inappropriately named South Africa Order-in-Council of 1891 authorised the High Commissioner for South Africa to establish by proclamation a legal system in the new territory of present day Zimbabwe. Acting in terms of this power under the High Commissioner, by proclamation of 10 June 1891, established a system of magistrates’ courts in Mashonaland.

The proclamation declared that the law to be administered shall as nearly as the circumstances of the country will permit, be the same as the law for the time being in force in the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope, provided no Act passed after this time there shall be deemed to apply to the said territory.

When the pioneer column arrived in Mashonaland, Jameson appointed himself the chief magistrate of Mashonaland. Jameson had abandoned his thriving medical practice in Kimberley, South Africa, to try his luck in the new goldfields.

To assist him with his work, a prosecutor named Alfred Caldecott was appointed. As the chief magistrate, he was the highest judicial authority within the territory. Jameson was so powerful that he issued instructions to Colquhuon despite the fact that he actually held no official title or position. He was Rhodes’s point man in the colony and enjoyed incredible political power.

It was not long before the aggressive medical doctor forced Colquhuon to resign as administrator. Jameson immediately replaced him by assuming the role of administrator, but continued to be chief magistrate as well.

Jameson now became the judicial and administrative chief of the territory — a combination of executive and judicial responsibility would be considered an abomination today.

But Rhodes knew that judicial and political power needed to be aligned for his project to succeed. Politicians with the support of the judiciary are more powerful.

The 39-year-old Jameson now had absolute authority over the administrative machinery of the colony. He took under his wing the half-a-dozen police officers Colquhuon had appointed as magistrates.

As chief magistrate, Jameson had the powers of a High Court judge. Yet he had no legal training.

As W.D. Gale puts it in his book One Man’s Vision: “He was a medical man, with no legal training whatsoever. Law books had no meaning for him and he usually tried his cases without their aid, depending on his own common sense to arrive at a reasonably just decision. The necessity of maintaining law and order was his principal guide.”

During 1892, Jameson and Caldecott became worried about the rise in deaths among white invaders which appeared suspicious. In fact, the rumours were worrying Rhodes as they were circulating in England. There was a serious political risk that the Crown could withdraw the charter on account of this lawlessness.

Jameson was very clear about this political risk. The system then resolved to make an example of any person who was accused of causing the violent death of another.

The unfortunate example fell on the head of one Jewish fortune-hunter named Louis Andries who was accused of murdering a fellow fortune-hunter somewhere between Fort Tuli and Fort Victoria on their journey from the Transvaal to present-day Harare.

Andries was arrested and charged with murder. His trial was before Jameson and four assessors. Caldecott was the public prosecutor and Andries was defended by Harry Kinloch. It seems Kinloch was a multitasking lawyer. He combined bar skills with hunting down Ndebele kings. He subsequently perished together with Allan Wilson at Shangani River while pursuing King Lobengula.

The Andries case seemed to depend entirely on circumstantial evidence. Most settlers believed in Andries’s innocence. The evidence was in some respects weak. At the end of the trial, Jameson and the four assessors adjourned. They returned within 30 minutes of adjournment and announced their verdict.

Jameson pronounced it thus: “Prisoner at the bar, you have been found guilty of murder. As a doctor it has always been my study and purpose to save life and now I am bound to take it away.”

It is reported that Jameson then with great emotional struggle ordered that Andries be hanged by the neck until he is dead. It is said Jameson then collapsed in his chair and had to be assisted from the court. A weak chief justice is not a good thing — at least in the eyes of his or her appointees. It could not have escaped the notice of the BSAC that the person in whom they entrusted justice had no courage to dispense it.

It was required that such sentence be confirmed by a higher colonial authority based at the Cape. Once the sentence was confirmed by the High Commissioner at the Cape, as required by law, Andries had to lose his life at the hands of the state — rudimentary as that concept of state was at the time!

It must have come as a surprise to the pioneers that the locals did not have gallows to hang the condemned. In the circumstances, a 20-foot high gallows had to be constructed in what is today known as Africa Unity Square in Harare.

Of course, there was another shocker. The locals had no hangman to take a fellow human being’s life at the instance of the state. The pioneers had to find one amongst their number. A down and out settler named Morton thought this was a lucrative venture. He agreed to act as the hangman. On 17 April 1893, Andries was hanged still pleading his innocence. The hanging was to be done at 8am. Jameson secretly changed the hanging time from 8am to dawn in order to avoid spectators.

For his troubles, Morton, the pioneering hangman, became an outcast in all of Salisbury, shunned by all and sundry for having acted as the hangman. This probably explains why from then on the name of the hangman is a state secret to this day.

There was equal concern about reports of brutality meted out against natives by the settlers. Jameson and Rhodes were concerned that such reports could result in the cancellation of the charter.

Jameson therefore had the responsibility to ensure that there appeared to be just treatment of the natives. This was important for politics in England.

Once the gallows were lubricated with white blood, it became easy to hang the natives — not that Zulu Jim was originally a local. With the Mashonas enjoying the reputation of leaving employment after a few days or weeks and being unreliable, one Marondera farmer, James Grady, considered it good fortune to employ one Jim — a Zulu, as his given monicker suggested.

He had come up from Natal, South Africa, employed by a wagon driver. After the farmer’s cattle went missing, Grady suspected Jim. In turn, Jim offered to show the farmer where the cattle were.

The farmer, out of caution, put manacles on his employee-suspect and headed out with his friend, a neighbouring farmer named Mackenzie, wife and child. Somewhere during the cattle recovery trip, Jim managed to grab a firearm in the wagon and shot Grady, his wife, child and Mackenzie. Grady survived, though badly injured.

Grady gave his evidence from the hospital bed and subsequently died, bringing Jim’s body count to four. Jim went on the run. He turned up near Mukuvisi in present-day Mbare and was recognised by a native named Charley who was a brickmaker.

Jim sent Charley out to buy some tobacco and a pipe. Charley turned out to be a sellout. Instead, he went to the police in Victoria Street. Charley, in return for a reward, with the help of his brother arrested Jim and brought him to the police — ending a big police search.

When news of the capture of Jim spread, the mob of white pioneer drunkards and other sorts of characters tried to break into cells and government buildings in order to deliver vigilante justice to Jim. This inflamed environment was not in the company’s interests. It threatened the charter.

It was only the intervention of the administrator and chief magistrate Jameson that calmed the situation with the words: “You damned fools!

Don’t you know that the country is expecting a boom. A boom! But there will be no boom if the world sees there is no respect for the law and order. Are you going to be such fools as to ruin the boom, for which we have been waiting for so long by this stupid action? Jim has got to have a fair trial, however guilty he may be. Let the law take its course. If you carry out your plan you will ruin the coming boom!”

An eloquent exposition of the relationship between justice and economic performance delivered by the self-appointed chief magistrate who had not been to any law school.

But then the good excitable Dr concluded his speech by stating: “And if we don’t hang Jim you can hang me”. Now what justice awaited Jim? Jameson knew the political importance of appeasing the settlers.

Three days later and, true to his promise, Jameson and four assessors convicted Jim and sentenced him to death. There is no record of Jim being afforded legal counsel at his trial.

All such trial records had to be sent to the Cape for the conviction and sentence to be confirmed. Because of the public baying for Jim’s head, Jameson sent his report of the crime and trial to the high commissioner at the Cape by telegraph.

He asked the high commissioner to skip the usual formalities and delays that would be caused by use of the post. He wanted the high commissioner by return to confirm that execution could immediately be carried out. It was important for political ends that Jameson delivered swift justice against the native.

But Sir Henry Lock, the high commissioner, would have none of it. He replied:“… certain and not hurried execution is the greatest protection to the safe and efficient administration of justice.”

After receiving the high commissioner’s confirmation in due course, on 3 May 1893 (six weeks after the murders), Jim was publicly hanged on the gallows that were erected for Andries. Unlike with the Andries execution which was done before dawn contrary to the 8am time publicly announced by Jameson, Jim was hanged in front of a large crowd in the Fort area. Even in those early years, it was important for the colonial project to project a difference between white and black justice.

Father Hartmann was present to do his religious duties. It is said that Jim was handed a cup of brandy which he hastily swallowed before Morton the hangman hanged him. As G.H Tanser records tantalisingly: “But in the same week that Jim was hanged yet another violent death occurred at Borrowdale. Jameson sardonically suggested the scaffold should remain a permanent institution.”

Jameson subsequently became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony between 1904-1908. He died on 26 November 1917 during the First World War. In line with his wishes, his body was kept in a vault in England and it remained there until the end of the war. Before his death he had declared that he was to be buried next to his friend, Rhodes, at Matopos, out Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. After the end of the war, his body was then carried from England to Zimbabwe. On 22 May 1920, Jameson was buried next to his friend who had predeceased him in 1902.

By that time, rudimentary state and judicial structures had been established in Southern Rhodesia.

*About the writer: Advocate Tererai Mafukidze is now a member of the Johannesburg Bar. He practises with Group One Sandown Chambers in Sandton, Johannesburg. His practice areas at the Bar are: general commercial law, competition law, human rights, administrative and constitutional law.

You may like