Opinion

Political elites’ vacuous populism not serving Zimbabwean people’s interest

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksMIKE CHIPERE

IN a recent eloquent but rather dense article titled “Dynamics of the Zimbabwe crisis in the 21st century” adopted from a 2003 academic paper of a similar title, Professor Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni made strong emphasis that Zimbabwe must make an urgent and concerted effort to overcome the authoritarianism, violence, intolerance and hegemonic tendencies inherited from not only the liberation war but also pre-colonial traditions.

As a way forward, he made three important suggestions, the first one being that the division between the people and their leaders needs to be urgently closed and second a call for a new people’s constitution and a pragmatic ideology consistent with global developments, while at the same time not sacrificing local needs and demands of Zimbabweans.

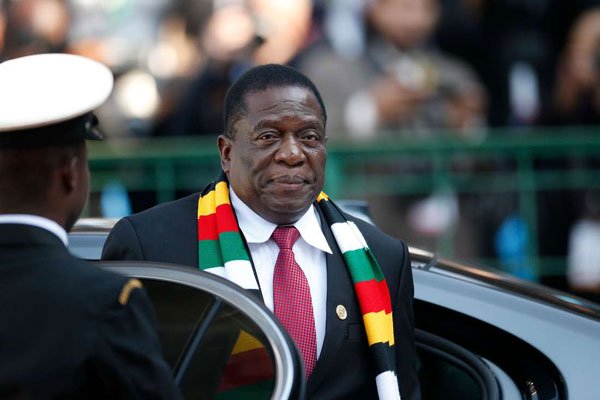

In a direct or coincidental response to his call for the eradication of the boundaries between the people and their leaders, we got President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s “new dispensation”, which is ironically steeped in bankrupt and tired ideologies from the past, and reinforced authoritarianism, violence and intolerance.

His executioners ranging from the lowly Zanu PF mobs to the feared Central Intelligence Organisation, military intelligence, the Ferrets Team, and other shadowy figures continue to routinely suppress and annihilate dissenting voices by violent means such as torture, abduction and outright murder.

As we speak, Mnangagwa’s regime is in the process of desecrating the people’s constitution that we got during the Government of National Unity. Through this and various other means, the Zimbabwe electorate remains sliced and diced (for consumption by a few) and in the process completely backtracked on Ndlovu-Gatsheni’s decade-plus call for Zimbabwean society to be saved from its current division into the “people” and “their leaders”.

Lastly, a pragmatic ideology never emerged from both the ruling party and all opposition parties; in fact, Mnangagwa recently said an ideology was a luxury.

The basis of the division stated above is partly because of nationalist populist ideology. In brief, populism is a type of political philosophy in which a country’s elite articulate people’s grievances in ways that appeal to the ordinary man and woman in the street, but in a manner that only serves the elite’s goals. Typically, the primary goal would be to gain political power, and all that comes with it. In a sense, populism is about the people but not by the people.

To appreciate how the ordinary men and women in the street have been manipulated via populism, we need to understand who the elites and/or intelligentsia are in Zimbabwe.

In this article, I broadly understand them to be intellectuals or other persons who strongly influence or have an interest in influencing politics and culture. I will limit my analysis to three important components: political elites (ruling and opposition party leaders), secondly academics, and lastly religious leaders. Musicians could also be included as an important constituent, but I believe the above three are the most problematic in the Zimbabwe socio-political space.

Although Ndlovu-Gatsheni critiqued populism in detail, some of the mechanisms that have been used in conjunction with populism and violence were left out. I will touch on the linguistic tools that are used to manipulate the people, in particular the usage of “passive verbs” by both the ruling and opposition parties during political campaigns. It goes like this; you want employment?

Vote for me and I will provide it to you even though this promise has never been fulfilled in the last 41 years. During the 2018 election campaign, Mnangagwa plastered Bulawayo with posters proclaiming that he will open previously abandoned factories, but he never did, their security gates are far more rusty from disuse than they were in 2018. You want “citizens’ convergence?”? Vote for me, I will provide it to you when I become president even though I picked up the phrase from foreign-sponsored non-governmental organisations and have no understanding of what it is or how to effect it.

In the rest of the article, I will examine how the political elites (including religious leaders) have used nationalistic rhetoric, populism and passive verbs to oppress the people and in the process retain power and influence in Zimbabwe.

Secondly, I will examine how academics acquire knowledge by abstracting local realities in ways that are largely inconsequential to the lives of ordinary Zimbabweans. In the conclusion and in next article, I will make a concrete proposal that differs significantly from the ones articulated or proposed by Ndlovu-Gatsheni.

Firstly, I will argue that as a nation, we will never be able to solve our problems unless we accurately identify and/or define them. Following that, I will articulate our problem, and propose a “third way” in which I intimate how the people can liberate themselves using the tools that are not too dissimilar to the ones that oppress them today. This will come in the form of a Zimbabwe People’s Charter “for and by the people” as opposed to populism which is “about the people but not the people”.

The charter will depend either on violence nor deceit via passive verbs, but active verbs which are concrete, measurable and actionable (possibly by the current government) or by the party which is going to win the 2023.

MDC’s intolerance and intellectual laziness

One of the repercussions of authoritarian populism is intolerance; Zimbabwe has not escaped this. Online newspaper comment sections and social media platforms are full of threats of physical violence, tribalistic and homophobic exchanges between people who simply disagree with each other.

MDC Alliance leader Nelson Chamisa’s supporters are strong adherents of the “Chamisa chete chete” (Chamisa all the way) ideology which assents to the view that nobody beside him is capable of delivering this country to the promised land.

Instead of appreciating that internal opposition can elevate their ideas and strategies, they label opponents enemies and sell-outs, just as Zanu PF does. In a recent video broadcast, Chamisa talked about citizens’ convergence. Thereafter, the phrase grew its own legs – gaining support from esteemed political scientists such as Professor Jonathan Moyo, senior MDC officials and social media activists. Unfortunately, Chamisa and all the people who continue to propagate and in some cases parrot the notion of “citizens’ convergence” have failed to define such an interesting idea. On social media, the phrase is routinely coupled with a passionate plea for Zimbabweans to register to vote — and that is confusing. One is left wondering whether voting in itself is some type of convergence.

Secondly, since the opposition is the only one that seems to be calling for convergence, does it mean that no other party is capable of converging. Most importantly, what and where is the agency that will make people converge? Do they converge merely because a charismatic personality said so? What does the current violence against the MDC as it attempts to campaign for the 2023 elections say about citizens’ convergence as a concept? Lastly and importantly, was it an example of “citizens’ convergence” when Zanu PF and MDC leaders mobilised Zimbabweans to kiss soldiers in the streets as they carried out a coup against the former president Robert Mugabe in 2017?

The ambiguity examined above has profound implications and yet very common in Africa and elsewhere. Nelson Mandela popularised the phrase “Rainbow Nation”, but several decades later, we rudely realised that racial harmony cannot be spoken into existence.

David Cameroon propounded the “Big Society”, but up today we do not know what he was on about. More recently, Donald Trump went by the adage “make America great again”, while unashamedly promoting a racist America in which people of colour are relegated to sub-human status.

Similarly, the MDC is throwing around vacuous phrases and “ngaapinde mukomana” (loosely translates to “the boy must get in”) slogans, but I think it is only fair that the boy explains why he should be allowed to be the next president. This has been pointed out by several analysts, but the response that if he does, his enemies will steal his ideas is unacceptable.

Firstly, judging from past political manifestos and other public commentaries, there is no evidence that he has a credible plan and I dare his most ardent supporters to articulate it beyond his desire to be the next president of Zimbabwe. Secondly, if his enemies steal these mysterious ideas or strategies, what does it matter if they would be beneficial to the long-suffering people of Zimbabwe?

The new but old dispensation

Historical and contemporary evidence from Zimbabwe clearly shows that Zanu PF leaders have perfected the art of appealing to people’s grievances just enough to serve their own purposes. During the liberation struggle, they mobilised people against racial segregation, but at the same time political and military leaders led lavish lifestyles in urban Lusaka while young poor soldiers risked their lives in the jungle at the frontline.

They preached unity while fuelling ethnic tensions, denigrating nationalist leader Joshua Nkomo as just a Ndebele leader, and following that up in post-independence Zimbabwe by ethnic cleansing, massacring unarmed Ndebele civilians in Matabeleland and the Midlands regions.

Furthermore, they campaigned for votes by promising people the redistribution of resources, while pursuing neoliberal policies such as the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme, etc.

They implemented land redistribution policies on the basis that a white minority group cannot own over three quarters of arable land while the majority are landless, and yet today over three quarters of A2 farms are in the hands of a minority group, the political elites in government and the military. They promised peace and human rights while actively engaging in violent purges such as the extrajudicial executions to quell the Nhari rebellion, the murder of Hebert Chitepo, Josiah Tongogara, shooting of Patrick Kombayi and, more recently, abductions and sexual assault of opposition activists.

Miseducated intellectuals

Zimbabweans have a fetish for education and the titles that go with it. It is not uncommon to hear a Zimbabwean proudly boast about how educated we are as a nation and this comes from the fact that the post-independence Zimbabwean government did indeed generously invest in education. Unfortunately such self-praise conflates literacy with education, and secondly it also shows lack of awareness of the fact that the colonial education system may have produced clever people, but not many great thinkers. I have met black Zimbabweans in South Africa who proudly bragged that their child attends a school where they do not learn any “bantu” languages. It was evident he was not aware how well he validates colonialism and its drive to deny Africans not only their languages and culture, but epistemologies (knowledge systems and what counts as knowledge).

At Independence there were rumours that Mugabe had seven university degrees. I am not certain whether that is an urban legend or true. Besides that, there are reports that in the 1960s he was nominated to lead Zanu PF because of his eloquence and phony British accent.

In reality, he was a black man on the outside and a wannabe English gentleman in the inside. His wide range of University of London degrees equipped him with exactly the same intellectual tools as those of the British architects of colonialism and not much more. People voted for him in the belief that the benefit of his education would somehow accrue to them. His wife recently tried to hoodwink potential voters into believing that she was capable of inheriting the presidency from her husband by concealing her lack of sophistication and intellectual capacity with a fraudulent University of Zimbabwe PhD.

Within the Southern Africa academic circles, it is widely known that some Zimbabweans (including politicians) are buying degrees from South African universities. In addition to the fraudulent degrees, it is also very common for senior public figures to acquire degrees from unaccredited universities.

Despite the practice of acquiring educational degrees as a means to gain unwarranted authority and prestige together with the legacies of colonialism briefly introduced above, Zimbabwe has had its fair share of influential academics both inside and outside government and these include Ibbo Mandaza, the late Sam Moyo, Brian Roftopoulos, Jonathan Moyo, Ngwabi Bhebhe, Eldred Masunungure, Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, up-and-coming ones like Blessing Miles Tendi and this is by no means an exhaustive list. At the initial stages of their scholarly endeavour, their fieldwork is typically based on a segment of Zimbabwean society, from that they gain scholarly recognition and appointments at prestigious universities and thinktanks.

Despite all that, there is not much evidence to support the idea that the benefit of their education accrues to the average person in Zimbabwe.

If it does, I am not aware of a technology, innovation or original theory that is attributed to a Zimbabwean and benefitting our nation today. Undeniably, there are some academics who have made contributions which could have positively affected policy and practice.

Regrettably such academics are either ignored or incorporated only to serve the narrow interests of those who hold political power. An interesting example is Jonathan Moyo, a political science professor whom according to my own assessment is not given enough credit for the amazing contributions that he made to the music industry and creative arts in Zimbabwe.

Beyond that, he was at one time reduced to or willingly acted as a political tactician for Zanu PF. Similarly, Mandaza and many others have over the years been incorporated into policy formulation, but were discarded as soon as their contributions ceased being amenable to regime survival and security.

I also have a suspicion that the Zimbabwean government does not have a policy research department. Ministers seem to make decisions on the basis of anecdote and personal whim. For example, the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic seems to have been a “cut and paste” from developed countries’ government institutions.

Secondly, a government minister recently banned the importation of second-hand cars older than 10 years. Possible reasons for a decision like that are environmental concerns, for example carbon monoxide emissions and to protect the local car industry. But oddly enough, Zimbabwe does not have a car industry and barely has a functioning industrial sector that could produce carbon emissions that warrant this policy.

The “monkey see monkey do” Rhodesian education system was never adapted for a new Zimbabwe. I will provide a few examples which include the ministry of Education and ministry of Finance. The former made it compulsory that Ordinary Level students must pass English and yet, according to colonial education policy documents, this was based on the belief that indigenous languages are not fully developed and have not yet taken a literal form. Other colonialists went as far as proclaiming that Bantu languages have no adverbs and prepositions. Despite such stupid presumptions, every post-independence Zimbabwean minister of Education pursued this policy. Why would anyone need to pass English in order to teach Shona or Ndebele for example?

Despite that the Zimbabwe fiscal policy space is currently occupied by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank blue-eyed-boy and University of Cambridge-educated Professor Mthuli Ncube, the economy and currency are on a tailspin. He recently celebrated a budget surplus and yet over 96% of the population have no jobs.

Furthermore, in recent research I came across households which survive on a single meal per day, saw disabled people begging for food in the streets, destitute people sleeping in the streets and dying of hypothermia, mothers standing at the supermarket pay-point struggling to decide whether to buy one loaf of bread or two and wondered how and where they feature in Ncube’s self-celebrated budget surplus.

Aside from this micro perspective, he does not seem to have any qualms that although the IMF imposes a demand for a balanced budget on Zimbabwe, there is historical evidence which shows that the United States consistently achieves the highest rate of employment only when they run a budget deficit. Similarly, his predecessor, Tendai Biti, popularised the adage “we eat what we kill” in reference to cash budgeting impositions on Zimbabwe while the US accrues one of the highest budget deficits in the world. But besides that, not even households can survive only on what they kill. The two do not have much respect for each other, yet both deliberately or naively worship on the altar of neoliberal ideology which destroyed several African economies. Furthermore, none of Zimbabwe’s post-independence Finance ministers have ever challenged the IMF for forcing Zimbabwe to repay debts illegally accrued by the Rhodesian government to fund a war against black majority rule and in pursuance of racial segregation.

I have relatively similar academic qualifications as Ncube whom my sister remembers as a “straight A” University of Zimbabwe classmate, but I know that he does not have any theoretical tools which are of much use to Zimbabwe. His conceptual apparatus will only work where the recommended texts that he read at the universities of Zimbabwe and Cambridge were authored.

The Zimbabwean opposition is dominated by lawyers whom together with opposition party leaders approached the US government to impose sanctions on the government. Some argue that they are merely targeted sanctions, but they are not.

In the UK, for example, if any individual or business declares business dealings with Zimbabwe, they will have their bank account closed. Nonetheless, their invitation for sanctions was based on genuine political grievances. One of which was lack of respect for property rights of a minority group of white Zimbabwean farmers who lost land when it was redistributed to landless black Zimbabweans.

In their passionate fight for the rights of a few white farmers, the predominantly black MDC lawyers made a choice to overlook fellow blacks who lost almost all their land to the Pioneer Column mercenaries just a few decades ago. This does not demonstrate any independent thinking but an ability to memorise Roman Dutch laws as received during and after the colonial era.

This lack of foresight and failure to take cognisant of the fact that property rights issues require a new perspective grounded in the southern African context is going to be problematic in the future.

The same arguments that property acquired by white people via cheap black labour, violence and dispossession deserves protection under the law can also be used by the black political elites who are looting Zimbabwe’s resources and concealing the proceeds in offshore accounts. It will be near-impossible to detect criminality in the paper trail, but in the unlikely event that it is uncovered, they will ask the questions: In what ways is theft and corruption any worse than forced labour (chibharo), land dispossession, and outright abuse of black people by white Rhodesians?

Monetising God

Zimbabwean newspapers, radio stations and social media are full of first-hand anthropological accounts about the strong association between religion and the occult, but researchers and policymakers have not paid attention to this, possibly because when the white men came to Zimbabwe, they proclaimed that witchcraft does not exist.

If not that, perhaps it is because of religious freedom doctrines borrowed from distant others whose 12-year-old daughters will never be raped or married off to 60-year-old men who visit traditional doctors (aka spiritual fathers) in West Africa and come back a “man of God”.

These men of God (predominantly the prosperity gospel sect) are pacifying the long-suffering people of Zimbabwe to believe in a Jesus who does not say no to the prayer of congregants who pay them a generous tithe which they lavishly spend on behalf of God.

In the process, they become millionaires who live in mansions while over three thirds of their congregants live below the poverty line. One does not need a theology degree to know that God cannot provide a job where industry has been shut down or park a new luxury car on anyone’s driveway just as Bushiri (a so-called man of God) did a Rolls-Royce for his six-year-old child. Faced with poverty and destitution, many continue to be financially abused, sexually molested and alienated from loved ones by self-appointed men of God who have found fertile ground in Africa to monetise God based on fraudulent religious authority.

Conclusion

The above synopsis suggests that the elites have not made much positive contributions to the people of Zimbabwe. More specifically, political elites have not produced a pragmatic ideology as called for by Ndlovu-Gatsheni, neither have they demonstrated an ability to remove the people-versus-elites rift.

The research output by Zimbabwean academics is clearly beneficial to them, the countries where they work, their funders and academic disciplines in which they are situated, but inconsequential to the lives of the ordinary Zimbabweans.

The church has managed to put God on sale to the lowest and highest bidder. The origins of the tendency by Zimbabweans not to have any scepticism to both credible (and equally questionable) knowledge claims (and/or authority) has historical precedents, some of which have been examined in previous sections.

In brief, Ndlovu-Gatsheni mentioned the “big man” syndrome and I would add praise poetry in which, through totems, we ascribe to the living the courageous qualities, military adventures and virtues of people who died hundreds of years ago. In that, we also deliberately choose to unsee their folly. The previous examples provided in the introduction supports the view that populism as an ideology is dangerous and irrational; it appeals to human instincts in ways that are not necessarily beneficial to society.

Despite his ineptitude, it is likely that Mnangagwa will emerge victorious from the 2023 elections, not because people love him but his monopoly to violence, vote-rigging and unfettered access to national broadcasting services paid for by the people of Zimbabwe.

Lastly and most importantly, Mnangagwa is likely to win because Zimbabwe does not currently have a formidable opposition party. It is not too late for those who believe in the “Chamisa Chete Chete” dogma to demand viable political thought and strategy from him because as we speak there is no evidence that he has any. The response that it is a strategic move to play daft is nonsensical. Voting him into power merely on the basis of charismatic authority will be as huge a mistake as was overlooking Nkomo in 1980 and voting Mugabe into power on the basis of his eloquence and perceived level of education.

Equally, it is not impossible for a viable opposition party headed by a more intelligent leader than the ones we have had thus far to emerge. If that were to happen, I am not convinced Mnangagwa and his vote-rigging arsenal and violence would help him win the next election. Ian Smith had far more violent means to retain power, but he lost the 1980 elections.

Given the gloomy realities outlined in this article, what is the way forward?

I believe it is to be found in the Zimbabwe People’s Charter which will be examined in detail in a follow-up article. In brief, it will provide practical solutions that stem from the argument that the Zimbabwe problem is greed for money, wealth and power. Some like Ncube who has most probably read Friedman will perhaps argue that greed incentivises individuals to innovate and in the process grow the economy, but I am aware that there is abundant contrary evidence to that line of argument.

Others will hold the view that the Zimbabwe problem lies in poor leadership, corruption, inequality and authoritarianism. In my humble view, these are mere outcomes of greed for money, wealth and power. The Zimbabwe People’s Charter goes to the root of our problems as a nation.

*About the writer: Dr Mike Chipere, is an affiliate of the Human Economy Programme which is housed at University of Pretoria. His research interests are in development finance, fintech, convergence of money with technology and, more recently, decoloniality. Views expressed in this article are his own and do not represent any organisation or persons.

You may like