News

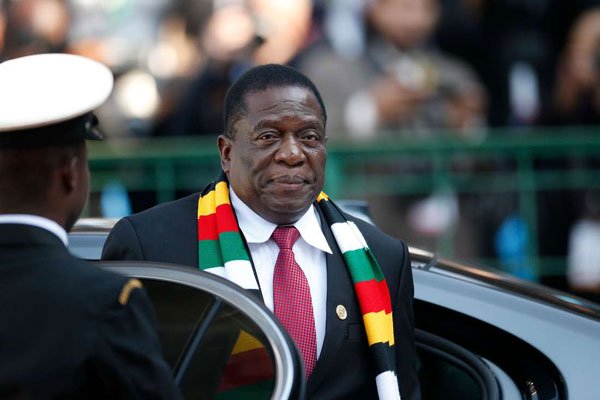

Mnangagwa’s oligarchs: Heirs of Cecil Rhodes

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksAS Zimbabwe’s economy has spiralled down, with one million economic refugees in South Africa alone and ordinary people facing shortages of food, fuel, medicine and shelter, there is a class of people who have done extremely well out of the system.

The poster child of this business model is Kudakwashe who despite multiplying scandals has built an empire that spans almost all key sectors of Zimbabwe’s economy. He has done this by cutting corners, setting up shelf companies and hiding behind proxies. But Tagwirei is not alone.

Among the “colourful” characters who regularly dine in the splendour of the Meikles Hotel while awaiting their friendly chats at State House with President Emmerson Mnangagwa are a Nigerian oil tycoon whose company has just spilt two million barrels of crude into the fragile Nembe Creek in the Niger Delta, and a shadowy Belarussian “consultant” who was arrested in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) last year on suspicion of arms dealing – which of course he vociferously denies.

But if you stop and listen in the dining room you will hear the voices of many languages. Cecil Rhodes always stood at the nexus of political and economic power. Not only did he create two of South Africa’s most successful mining companies – De Beers and Gold Fields – but he was prime minister of the Cape Colony and a representative of British imperial interests during the scramble for Africa.

He used his wealth and connections to shake down African chiefs for mineral concessions, the most egregious being the treaty he signed with Lobengula, King of the Ndebele, that opened the way for the exploitation and colonisation of Rhodesia. Rhodes might recognise his latter-day successors by behaviour, but not all by appearance.

The coterie of businessmen that swarms around Zanu PF are both black and white, Zimbabwean and foreign. Some are billionaires, some come from old money and some are pure products of patronage, having been spun from the Zanu PF mill.

What they have in common is that their success in business is tied to their proximity to political power in Zimbabwe. The actual relationships between political and economic power in Zimbabwe are opaque and often shifting. They are subject to political intrigue within Zanu PF, the military and the state.

For many businesses it is simply a matter of survival – as it was for those white farmers who bought themselves protection from the ruling party during the land seizures initiated by Robert Mugabe two decades ago while their neighbours were evicted, often violently.

During the past year a series of devastating reports by groups such as Sentry and ARC, published in Daily Maverick last year, have exposed the swampy cartels and corrupt dealings of Zimbabwe’s political and business insiders.

These, the beneficiaries of Zanu PF and government connections, have made it their business to loot and siphon off state funds, to hog contracts and ultimately to impoverish ordinary Zimbabweans.

The dire state of the economy and the mutating politics of patronage have driven the Zanu PF regime, which was once a proud liberation movement, to subsist on a mixture of banditry, corruption and state capture.

But what of the other side of the ledger: the businessmen who have bolstered the ruling party for the past 42 years and who continue to enable the regime of Mnangagwa?

Through covert and overt support of the ruling elites in Harare, these businessmen have reaped economic benefits while maintaining a pervasive influence on economic affairs.

With elections looming, Zanu-PF will be looking to them once again for donations for its campaigns and to grease the palms of office-holders in order to hold on to the protection of the ruling party.

The 2017 military coup that removed Robert Mugabe from office has left the economic system he honed to serve the Zanu PF elite largely untouched, with only a slight reshuffling of loyalties and personalities.

The leading figure among the group of black businessmen that have captured the political system is Tagwirei.

But while Tagwirei is well known and increasingly reported on, there are others who operate in the shadows, such as the Nigerian oil tycoon Benedict Peters. He recently acquired a lucrative haul of platinum assets on the back of his relationships with Mugabe and with Mnangagwa.

While Peters’ dealings in Zimbabwe have flown largely under the radar, he has been in the news in Nigeria recently because of a spill on Oil Mining Lease 29, owned by his company Aiteo, which spewed two million barrels of oil into the populated riverine areas of Nembe Creek.

It took 32 days to seal one of the most toxic blowouts in the history of Nigerian oil spills. Peters’ name cropped up in the recently released Pandora Papers, alongside another veteran crony of Zanu PF, Billy Rautenbach, who has been placed under EU and US sanctions for his support of the Mugabe regime.

Although he was close to the Mugabe administration, Mnangagwa has long been a key contact of Rautenbach. The two were involved in mining deals in the Democratic Republic of Congo during the 1990s when Zimbabwe sent its army to rescue the regime of Laurent Kabila.

There are a number of significant white businessmen who are close to the president, among them the Rudland brothers who are seeking control over South African sugar producer Tongaat Hulett. A new factor is the Chinese businessmen who now wield ever greater influence in Zimbabwe and especially with Mnangagwa.

Chinese business holds a special place in Zimbabwe’s economic and political space, drawing on Beijing’s support of the ruling party during the Independence war from 1964 to 1979. Some Chinese businesses have gone into business with the Zimbabwean army, especially in the mining sector.

Mnangagwa’s rogue’s gallery

Kudakwashe Regimond Tagwirei

Kuda Tagwirei is the most influential black Zimbabwean businessman to emerge in the country in the last decade. His empire straddles many sectors, from mining to fuel, logistics, banking, construction, healthcare and agriculture.

Tagwirei has captured the system, ensuring that many state tenders go to him or his proxies. In return, he funds not only the Zanu PF party but provides hefty kickbacks to influential cronies within the government.

Tagwirei commands enormous influence in the corridors of power in Zimbabwe. He was put under United States sanctions in August 2020 for alleged corruption and helping Mnangagwa’s government.

He is closely connected to the military and has provided funding for some of the economic projects run by the army. After working in government and the private sector, in 1995 he formed Sakunda Holdings, his most recognised company, which sits atop his vast and often complex business empire.

It has subsidiaries in fuel distribution, petrol filling stations, commodity trading, road construction and agriculture inputs, among others. Tagwirei’s growing influence was noticed during the final years of Mugabe’s rule.

But after Mnangagwa came to power in 2017, the 52-year-old’s business empire rapidly expanded as he snapped up strategic mining assets as well as companies in the financial services sector and received lucrative government tenders.

Tagwirei’s proximity to Mnangagwa and his government has fuelled widespread accusations of state capture. He is a distant relative of the President and the two come from the same rural Midlands province. He is the sole supplier of buses to the state bus company, a deal he got without going through a tender process.

His influence in government was on display when his father died in May 2018. The president, most members of his cabinet and security chiefs attended the funeral in rural Midlands, which shut government business in his honour, an extraordinary feat for a private citizen.

Sakunda Holdings was embroiled in controversy after it emerged in Parliament last year that it had cut corners to secure a US$3 billion deal to supply farming inputs under a government programme without going to tender.

Tagwirei made money from holding the monopoly on importing and selling fuel. For a while, under Mugabe, Tagwirei had a contract to import duty-free fuel, ostensibly for power generation at Sakunda’s plant in Dema.

But, instead, the fuel was sold to the public at huge mark-ups. The media-shy business tycoon knows how to secure political influence. He has donated several cars to the Zimbabwe Republic Police and is one of the biggest funders of Zanu PF. In 2018 he bought the party a fleet of vehicles for its election campaigns and purchased cars for the first lady and Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga.

A recent report by the USbased The Sentry, based on a trove of documents from a whistle-blower and court records, exposed how Tagwirei, through shelf companies in South Africa and Mauritius, tightened his hold on the Zimbabwean economy despite the US sanctions.

In December last year the government of Zimbabwe unexpectedly announced that it had formed a new company, Kuvimba Mining House, which is now the owner of platinum, gold, chrome, and nickel mining assets previously owned by Tagwirei. The government has not tabled any proof that it paid for the assets, leading to concerns that Tagwirei remains the owner and that authorities are trying to shield the businessman from the impact of US sanctions.

Through a range of proxies such as the Fossil Group, owned on paper by Obey Chimuka, Tagwirei continues to win lucrative government tenders, with a recent Government Gazette revealing that the Fossil Group had won state jobs amounting to US$45 million in the past five months, more than any other company.

Chimuka is widely known in Harare circles as a front for Tagwirei.

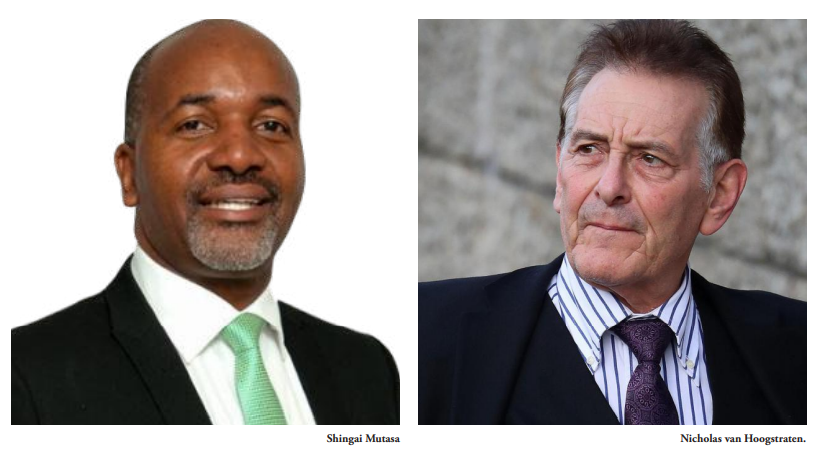

Nicholas van Hoogstraten

Van Hoogstraten has been infamous in England and Zimbabwe for decades. Born in Shoreham, West Sussex, in 1945, he dealt stamps as a profession when he was a schoolboy and by the age of 22 was a millionaire, one of the youngest in the country at the time.

He is reported to own around 350 properties in Sussex alone and divides his time between Sussex and Zimbabwe, where he has multimillion-dollar business interests, including real estate. Van Hoogstraten has for years been close to the Zanu-PF government, including Mnangagwa. He regularly funds the ruling party to earn political favours.

In the past, the outspoken tycoon has helped bankroll troubled stateowned companies, which increased his clout within government circles.

Van Hoogstraten’s net worth is unknown, but he is a major investor on the stock market and has a large farming estate in the Midlands province, where Mnangagwa comes from. He owns several commercial properties and apartments in Zimbabwe’s major cities and is one of the few white businessmen to own a string of properties in the townships.

Van Hoogstraten is an activist shareholder in Rainbow Tourism Group, the country’s second-largest hotelier, and Hwange Colliery, which is majority-owned by the government. One of his financial outfits, Hamilton Finance, named after one of his sons, has made millions lending to desperate Zimbabweans who put up their properties as collateral but often end up defaulting.

Shingai Mutasa

Mutasa is considered one of the richest black businessmen in Zimbabwe and has a long history of deal-making, dating back to the early years of Independence.

Media-shy and soft-spoken, Mutasa is well regarded by Zimbabwe’s ruling elite, to whom he has unlimited access. The tycoon has interests in agrochemicals, hospitality, insurance, and investment management in Zimba bwe and three other African countries.

Mutasa studied in the United Kingdom and returned to Zimbabwe at Independence in 1980 to join a commodity-broking family business.

In 2010, Mutasa registered a new investment company, Masawara plc, in Jersey. The new firm bought TA Holdings, delisted the company and renamed it Masawara Zimbabwe, where he is the chief executive officer. In the insurance sector, Masawara controls Zimnat Lion Insurance, Zimnat Life Assurance, Grande Reinsurance and Minerva Risk Advisors.

During the same year, Masawara bought BP Shell’s local franchise and renamed it Zuva Petroleum. The deal went through despite opposition from black economic empowerment groups.

Andre Zietsman

Zietsman is arguably the white businessman who is seen most often with Mnangagwa these days. He owns a company called Bitumen Construction, which has received several large contracts in the Eastern Highlands and for the rehabilitation of the Harare/Beitbridge road. Zietsman has had ties with the ruling party since Mugabe’s days.

Before the coup he was a business adviser to Grace Mugabe but quickly changed allegiances. He built his fortune on contracts to rehabilitate and build roads throughout Zimbabwe.

To Bitumen’s credit, it is the best road construction company in Zimbabwe at the moment.

Benedict Peters

Nigerian billionaire Benedict Peters has been looking to diversify his investment from oil, gas and energy under the Aiteo Group.

Aiteo controversially acquired Oil Mining Licence 29 from Shell in 2015. Peters had a close relationship with the then minister of petroleum, Diezani Alison-Madueke, who faces multiple investigations for corruption.

He was recently named in the Pandora Papers exposé as operating as a front for the minister. Peters’ relationship with Mnangagwa dates to 2003 when Mnangagwa made an official visit to Ghana as Speaker of Zimbabwe’s Parliament.

The two have kept in touch over the years. Peters first tried to invest in Zimbabwe during the era of Mugabe when he said he was prepared to invest up to US$2 billion in platinum and gold mining.

Peters’ plans did not immediately materialise as he was held back by bureaucracy and red tape. His fortunes changed when Mnangagwa came to power in 2017 with his “open for business” mantra.

Bravura Zimbabwe, Peters’ local mining vehicle, is exploring for platinum on a disputed concession that previously belonged to the South African company Amari.

Peters’ influence traverses the structures of government all the way to the president. He has a personal relationship with Mnangagwa, and the Bravura mining venture is spearheaded directly from Mnangagwa’s office.

Mnangagwa sees this as one of the signature projects that will help deliver him re-election in 2023. Peters has direct access to Mnangagwa but also deploys other links, as he is based outside Zimbabwe.

He has direct access to Mines minister Winston Chitando and is close to Gerald Mlotshwa, Mnangagwa’s son-in-law. Sources at the ministry of Mines say Chitando is an informal adviser to Peters on Bravura’s platinum venture, using his extensive background in platinum mining and that Chitando is being paid for these services. This allegation has not been proven.

Charles Davy

Davy is one of several rich white businessmen with strong ties to Zanu PF. He owns HHK Safaris, which describes itself as Africa’s biggest safari operator and boasts of lodges and exclusive rights to a hunting area covering 2.2 million hectares in Zimbabwe and Cameroon.

At the height of the land invasions in 2000, Davy’s HHK Safaris in western Matabeleland was untouched due to his strong links with the ruling party. He is the father of Chelsy, a former girlfriend of Prince Harry.

Like most Zimbabwean business tycoons, the millionaire shuns the media and public spotlight. He was previously in business with Zanu PF MP Webster Shamu but sold his shares to concentrate on HHK Safaris.

Born in South Africa in 1952, Davy was nine when his family emigrated to the then Rhodesia. He started in cattle ranching in the south-east of the country in the late 1970s at the height of the Independence war, which forced him to abandon the business.

His big break came in the late 1980s when he oversaw the purchase of Liebig’s farm in Matabeleland. Davy sold off the ranch’s cattle and brought in wildlife, transforming it into Lemco Safari Area and, by the late 1990s, the hunting business had made him a millionaire.

As the land seizures started, Davy gave up four other farms, including a large estate near Harare and got into business with Shamu, so he could keep his prized safari ranch.

Tino Machakaire

Machakaire is a deputy minister in Mnangagwa’s government who is not shy to flaunt his acquired wealth.

The 40-year-old millionaire’s fortunes changed when he married Tagwirei’s sister more than a decade ago, which opened the doors to several business opportunities.

Machakaire’s main business is transport logistics, through his Tinmac Motors, which runs one of southern Africa’s largest logistics companies. His business has been helped by large government tenders, including deals to move farming inputs across the country, under the Command Agriculture programme, and fuel locally and in the region.

Machakaire sits on the boards of several companies that are owned by Tagwirei and lavishly donates to Zanu-PF. Machakaire and Obey Chimuka are widely seen as fronts for Tagwirei, although Machakaire is slowly establishing his own imprint.

The Rudland brothers Simon and Hamish

Rudland are millionaire brothers who started Pioneer Transport in 1995, growing it into Pioneer Corporation Africa through the acquisitions of other leading transport businesses.

The two are active shareholders on the local stock exchange and are close to Mnangagwa. While Hamish is the polished boardroom operator, Simon is a brawler who is not afraid to get his hands dirty.

He has made millions from his Gold Leaf Tobacco Corporation company, which he formed in South Africa in 2000. He has been accused of fuelling the illicit cigarette trade in South Africa by smuggling cheap contraband cigarettes from Zimbabwe, which he denies.

He was shot in his driveway in South Africa in 2019, which he blamed on the cigarette wars in that country.

Recently, Mauritius-registered Magister, a company owned by Hamish Rudland, undertook to underwrite half of the rights issue of one of Africa’s largest sugar producers, Tongaat Hulett.

That amounts to US$128.5 million and shows the financial muscle of the Rudland brothers. After the rights issue, Hamish Rudland could become the biggest shareholder in Tongaat, which has operations in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Botswana.

The Macmillan family

Ian Macmillan and his son Ewan have built a business milling and buying gold around the country from their base in southwestern Zimbabwe. The elder Macmillan is among a small but influential group of white businessmen that supports Mnangagwa’s government.

Although the elder Macmillan is retired, he remains influential with his vast contacts in Zanu PF, cultivated over the last four decades. The Macmillans, like other white business tycoons, are not immune to the factional battles that consume the ruling party.

They have been arrested in the past for illegal possession of bullion and gold smuggling, but acquitted or released after paying small fines. Ruling party sources say the arrests are always linked to factional fights in the governing party.

When one faction believes another is receiving more than its fair share of “bribes”, it usually uses the police and the courts to send a message, the sources say. It is a game that white Zimbabwean businessmen are well aware of.

In 2003, Macmillan and his son were arrested and charged for smuggling gold worth about US$68 million to South Africa through a syndicate. They were acquitted but have remained in the gold buying business.

Muller Conrad “Billy” Rautenbach

A Zanu PF benefactor, Rautenbach is a buccaneering white Zimbabwean businessman who has been surrounded by controversy for a long time. He has had business ventures in transport, car assembly, distribution, fuel and mining.

He spent the period between 1999 and 2009 as a fugitive from South Africa after fleeing the country when he was charged with corruption and customs tax fraud.

His company SA Botswana Hauliers later paid a R40 million fine, but Rautenbach never admitted any personal liability and charges against him were withdrawn as part of the 2009 settlement. Rautenbach is a major donor to Zanu PF, which has earned him a lot of influence in the government.

His controversial reputation flows from allegations that he uses his proximity to government leaders to gain favourable access to business opportunities. His major break came in 1998 when he was appointed chief executive of La Générale des Carrières et des Mines (Gecamines) by the then DRC president, Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

He was seconded to the position by the Zimbabwe government as payback for Harare’s military backing. It was reported then that Rautenbach’s position at Gecamines was secured in direct negotiations between Kabila and Mnangagwa.

In 2002, the UN Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo described Rautenbach as a man “whose personal and professional integrity is doubtful”.

In 2008, the company in which he was a minority shareholder, Central African Mining and Exploration Company (Camec), paid US$100 million to Mugabe’s government, providing the ruling party a lifeline for elections that year.

Sources have said Rautenbach was at the centre of the deal. At that time, Rautenbach had battles with the DRC government but he had close ties with Camec. When a Cabinet team approached him to raise funds for them, he asked for platinum concessions, taken from Anglo Platinum, to be given to him instead of the Chinese and said he was going to find a buyer for them.

He reached out to Camec, with which he had business dealings in the DRC, and it facilitated the US$100 million loan. He came out of the deal with US$5 million, plus shares in Camec. His ties to the ruling party landed him on the US and European Union sanctions lists in 2008.

In 2011, Rautenbach’s new company, Green Fuel, started producing ethanol and two years later was given a licence and monopoly to supply ethanol for fuel blending in Zimbabwe. Although Green Fuel’s ethanol is more expensive than imported ethanol, Rautenbach’s political connections have ensured he remains the sole supplier.

He has courted controversy by evicting villagers in southeastern Zimbabwe to expand his cane fields. The government has turned a blind eye to this.

The Pandora Papers, an anonymous leak of millions of documents from databases of 14 corporate service providers that set up and manage shell companies and trusts in tax havens, provided a partial window into Rautenbach’s more recent business exploits, including details about the significant financial losses sustained by Green Fuel.

Rautenbach is also a major shareholder in Western Coal and Energy Project, which is mining coal in western Hwange.

Jim Goddard

Jim Goddard of JR Goddard Contracting isn’t a crony as such but has worked very closely with Zanu PF people over many years and has one of the country’s largest engineering firms. He also has large land holdings which have been largely unaffected by the land reform programme.

Chinese businesses

Chinese businesses have mushroomed in Zimbabwe in the last 15 years, taking advantage of the country’s isolation from Western countries. Riding on the deep political ties between Harare and Beijing, the businesses are in mineral resource extraction, construction, agriculture and general trading. China is the biggest buyer of Zimbabwe’s tobacco.

Like many African nations, Zimbabwe is enveloped by Chinese influence, be it with regard to the political, military or economic class. China has provided loans to fund the upgrade of Zimbabwe’s two largest power stations and many of its firms are involved in diamond, gold, chrome and coal mining.

Global steelmaker Sinosteel and the Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group, which mines diamonds in the east of the country, are two of the most well-known Chinese businesses operating in Zimbabwe.

The Zimbabwe Defence College, which was built with a US$98 million diamond-backed loan, is a symbol and manifestation of the Look East policy adopted under Mugabe. The latest official data show that Zimbabwe owes China US$1.6 billion, most of it in arrears, but most analysts think the figure is much higher.

In terms of exercising control over political and strategic affairs, China is the only country that has invested in providing direct technical support to Zimbabwe’s state security apparatus and the Presidency.

Though the main role of the Chinese was to build infrastructure, its determination to exert influence has seen Beijing embark on a mission to project its technical and surveillance capacities by selling these to Zimbabwe’s security services.

China preaches non-political interference as a central plank of its foreign policy, but when Mugabe was toppled in a military coup in 2017, the then defence forces commander and now vice-president, Constantino Chiwenga, had just returned from an unannounced trip to Beijing.

To most political and security analysts, this was no mere coincidence but part of a well-thought-out strategy.

As in most countries in Africa, China’s power and clout in Zimbabwe can be recognised from the fact that despite numerous cases of rampant abuse by Chinese employers of the local labour force and a disregard of environmental laws, no hard measures have been taken by the government.

The military

Through its two investment vehicles, Rusununguko Nkululeko Holdings and Old Stone, the military is involved in off-the-national-budget commercial activities through mining gold in central Zimbabwe. The biggest mine is in Battlefields, west of Harare. The mine is believed to produce up to 50kg of gold a month and the Zimbabwe Defence Forces retain all the sales and do not remit any money to the government.

The military commercialisation in Zimbabwe happens behind a thick veil of secrecy and is highly elitist. It mostly involves top army management and select politicians and there is no evidence it is bringing institutional gain.

The presence of the military in high-value commerce presents a rich opportunity for coups in the future if not handled carefully. Several military officers individually own gold concessions around the country, with some of them partnering with Chinese investors. Separately, many rank-and-file soldiers have moved into illegal gold mining, leading to clashes with the police and artisanal miners.

At times this is done with the blessing of senior officers, who get to take a share of the earnings. The presence of the military in high-value commerce presents a rich opportunity for coups in the future if not handled carefully.

Several military officers individually own gold concessions around the country, with some of them partnering with Chinese investors. Separately, many rank-and-file soldiers have moved into illegal gold mining, leading to clashes with the police and artisanal miners. At times this is done with the blessing of senior officers, who get to take a share of the earnings.

Zinona Koudounaris

Koudounaris is a Zimbabwean entrepreneur of Greek descent who co-founded one of the biggest companies listed on the local stock exchange. Known among business associates as Zed, he started Innscor Africa Limited with his friend Michael Fowler in 1997.

What started as a chicken and chips shop has over the years grown into a diversified company with annual revenue of more than US$600 million and has spun off other businesses and separately listed them. From food manufacturing that includes bread, flour and maize meal, to poultry, meat, furniture and appliances and car parts, Zimbabweans interact with Innscor’s products daily. It would be hard to find a local household without an Innscor product.

The company cornered the market for basic goods. As one news report put it, “You don’t ask what Innscor owns, but what don’t they own.”

Koudounaris is at the centre of the company’s expansion drive and has been able to navigate the concerns of the Competition Commission due to his access to connections in the government. Innscor’s National Foods supplies maize and rice to army barracks.

But the army also has its own farms in the southeast of the country where it grows crops including maize. Typically, Koudounaris stays away from the glare of the media, preferring to be a backroom operator.

Koudounaris’s go-between with government and political functionaries is Musekiwa Khumbula, a former journalist and information ministry officer who works as a consulting executive for Innscor. Reports say many government officials and ruling party types throng Khumbula’s office seeking financial favours from Koudounaris. In 2016, Koudounaris and Fowler were named in the Panama Papers as having opened four companies in the British Virgin Islands and transferring money from their salaries, against the country’s forex regulations. The two were never charged.

Alyaksandr (Alexander) Zingman

Zingman is a Belarusian businessman who in 2019 was appointed honorary consul for Zimbabwe by Mnangagwa.

A year before, in March 2018, Zim Goldfields, a company jointly owned by Zingman and Viktor Sheiman was issued a special grant to prospect and mine for gold in Zimbabwe. Sheiman is a close ally of Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko.

Through Zingman, Mnangagwa’s government is importing buses and agriculture and mining equipment from Belarus, but few details on the deals have emerged. Zingman is the major link between the opaque multimillion-dollar deals being conducted by Harare and Minsk. Mnangagwa has pivoted towards Belarus as the Zanu PF government expands its economic ties to Eastern Europe.

This has been particularly galling for most Zimbabwean rights activists, who see the Eastern European country’s human rights record as a red flag. Zingman has been accused of being involved in several arms deals in southern Africa.

In March 2021, the 54-year-old Zingman, who travels in a private jet, was arrested by DRC security agents and spent nearly two weeks in detention before his release without charge. DRC authorities had suspected him and his colleagues of trafficking arms, an accusation he denied.

John Moxon

Moxon is best known as the longtime chairperson of Meikles Limited, one of Zimbabwe’s oldest companies, which has been in existence for more than a century.

Meikles has interests in retail, agriculture, hospitality, and financial and security services. Moxon’s mother was the daughter of the founder of Meikles, Thomas Meikle. Moxon (77) grew up in the family business and is one of the most recognisable faces of white capital in Zimbabwe.

Meikles sold its flagship hotel, Meikles Hotel, for US$20 million but still owns Cape Grace Hotel in South Africa and the Victoria Falls Hotel, which is a joint venture with African Sun Ltd. Other subsidiaries are tea grower and exporter Tanganda Tea Company and TM Pick n Pay.

In 2013, Moxon helped fund the purchase of hundreds of vehicles for the Zanu PF election campaign, the first time he had been publicly linked to the ruling party. The donation came some months after Meikles had announced that it was seeking a licence to venture into mining.

Although he is fading from the public spotlight, Moxon’s ties with Mnangagwa remain very strong. Meikles’ secretary, Thabani Mpofu, a former public prosecutor and former head of the MDC’s research department, also works full-time as director of the Special Anti-Corruption Unit in Mnangagwa’s office. — Daily Maverick.

You may like

-

ED launches Munhumutapa Challenge Cup

-

Diaspora Praise Without Diaspora Rights Is Political Dishonesty

-

New Army Appointments Bad News For Chiwenga Presidential Ambitions

-

ZANU PF’s Succession Politics, Is Not a Contest of Ideas but a Struggle for Access

-

Tagwirei at Zanu PF DZ meeting | Pictures

-

Zanu PF Annual Conference Review