Opinion

Human rights and the Johanne Marange Apostolic Church

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksIN recent years there has been a growing public outcry about patriarchal practices, gender hegemony, sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence within the African apostolic churches, particularly the Johanne Marange Apostolic Church (JMAC) in Manicaland province in Zimbabwe.

Studies have been done and books written on the subject of theology and human rights. The relationship between religion and human rights is both complex and inextricable.

While most of the world’s religions have supported violence, repression and prejudice, they have also played a crucial role in the modern struggle for human rights, as John Witte and M. Christian Green write in Religion and Human Rights: An Introduction.

Most importantly, religions provide essential centres of gravity and scales of dignity and responsibility, shame and respect, restraint and regret, and restitution and reconciliation that a human rights regime needs to survive and flourish in any culture.

A study, Gender-based Violence in African Apostolic Churches: A Case Study of Johanne Marange Apostolic Church in Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe, by Mavis Magede and John Mbwirire indicates that the inequality between men and women cuts across public and private spheres of life, and social, economic, and cultural, as well as human rights realms.

This has largely contributed to gender-based violence in the apostolic churches.

As a result of the significance of this subject matter, beginning this week The NewsHawks will serialise a PhD thesis by Zimbabwean academic Dr Mathew Mare titled A Theological Exploration of the Interface Between Johanne Marange Apostolic Church and Human Rights (With Particular Emphasis on Children and Women’s Rights) to stir and steer debate on the issue.

The study was done at the University of South Africa and supervised by Professor Leepo J. Modise.

Human rights, especially women and children’s rights, sit at the heart of The NewsHawks’ investigative journalism project — Centre for Public Interest Journalism — together with in-depth reporting and analysis, as well as public accountability.

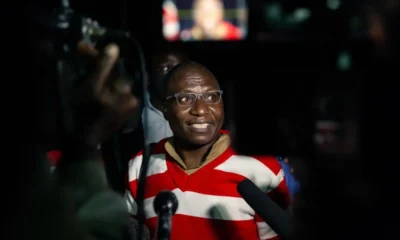

MATHEW MARE

THE desire to ascertain why there is a rancorous relationship between human rights and religious practices and customs motivated this researcher to dig deeper into the issue in order to unpack the same.

Amongst major points in this thesis was the unbundling of the nexus between human rights and the theological practices, teachings and rituals in African Independent Churches (AICs) in general, and Johanne Marange Apostolic Church (JMAC) in particular.

The major goal was to analyse theological practices and rituals, and to establish how these impact on the quality and nature of rights being accorded to women and children.

In doing so, this work employed a comparative analysis so as to understand the relationship between law and religion. The two disciplines have generally been studied in isolation, but here they are synthesised in order to come up with empirical conclusions on the subject.

Pertinent questions regarding church-state relations were answered by putting the two discourses in juxtaposition. This was achieved through a discussion of the background that motivated the researcher to undertake this study, presentation of statement of the problem, purpose as well as carefully thought-out research objectives, questions and the significance of the study.

An explanation of the research methodology for data collection and presentation of the structure of this thesis concluded the paper. A detailed presentation of these and more ensues.

Background

Women and children are predominantly regarded as vulnerable members of society due to the masculinity framing of the world, which is dominated by males. This is despite the fact that there has been a rise of feminism, which seeks to attain gender equality.

Even international organisations such as the United Nations (UN) had set goals for gender parity by 2020, which have not been achieved so far. Thus, gender issues seem to be complicated as women and children are still suffering at the mercy of men who dominate them due to the patriarchal nature of society (“Zimbabwe: Scourge of Child Marriage – Zimbabwe,” 2015:9).

To that end, religion has been seen as an enabler to the abuse of women and children who are treated as subjects instead of equals in almost all religions. In most of African Christianity, women are required to be submissive, to their husbands.

The situation is worse in Islam where women are denied the most basic rights and are treated as inferior subjects who have no say in framing their own trajectory. The situation is equally the same in African traditional religion.

Thus, the deprivation of rights to women and children is universal. Nevertheless, this thesis zeroes in on AICs (Musevenzi, 2017:1). The motivation is to seek a deeper understanding of the interface between human rights and theology, since religion seems to be playing a major role in sustaining masculinity framing of society, leading to the abuse of the rights of women and children.

The relationship between human rights and theology is predominantly determined by the church-state relations. The power matrix between the church and the state has serious human rights implications.

According to the church, the state is an offshoot of the church authority. The Lord’s Prayer, which is the fulcrum for the confession of faith by Christians, depicts the church as having power and the influence over the earthly dominion (Matthew 610ff). In Matthew 28:16, Jesus said to his disciples that all authority from heaven and earth had been given to him and he instructed them to go and make disciples of all nations. This command gave impetus to early church fathers to assume power over the state.

In addition, Jesus described Peter as a rock upon which the church was to be built and he bestowed absolute powers on him by declaring that whatever he bound on earth would also be bound in heaven (Matthew 16:18). Thus, scripturally, the power over the earthly dominion was vested on the church by Jesus himself.

Right from the onset and according to the scriptures, religion had power over the state. The Bible makes a claim that Abraham was made the father of all nations by God.

The bible also states that Israelites went to the prophet and demanded statehood and to be governed by a king like other kingdoms. Thus, a prophet was the one who had dominion over political and religious matters.

Abraham is considered to be the father of prophets and is the first person to be told by God that he would be given a nation state. In that kingdom, Abraham assumed political authority.

Later on came Moses; who was a prophet, tasked with a political assignment of creating statehood, Canaan, the land of honey and milk. While leading Israelites from Egypt in the wilderness, Moses assumed the role of a judge (Exodus 214, 18:13-27).

Thus, the prophet oscillated from religious responsibilities and roles to political and judiciary ones, which may imply that he had become an embodiment of the government itself (“Moses became a judge -Google Search,” 2016). Another case that shows superiority of religion to the state was when the Israelites rejected theocratic rule and Saul was appointed the first king of Israel.

Meanwhile, the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia is the most popular document that explicitly disempowered the church, which had enjoyed state monopoly until the treaty ended its hegemony over the state (“The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 and the Origins of Sovereignty,” 2021:1+).

The first proponents of the Westphalian thinking biblically saw in King David, who created the investiture dispute by anointing Solomon as his successor, a role previously designated to the office of the prophet.

David thus ended church authority over the appointment of kings when he appointed Solomon to be the King of Israel (I Kings 12:8). This departure was withstood the fact that David himself was appointed King by Samuel, a prophet. After Solomon, Israel was marred with infighting over kingship and prophets would be consulted as a last resort. Kings assumed dominion over state affairs, while prophets became kingmakers and religious advisers.

To that end, church-state power relations can be said to be as old as humanity itself, and this relationship has always influenced the rights of women and children sociologically, economically, and politically, as well as ecclesiastically. In terms of church state relations, King Henry VIII played a key role in limiting the powers of the church by questioning the church’s authority.

Henry was the first king to issue an Act of Parliament in 1534 to enable him to be the supreme head of the English church (“Act of Supremacy 1534,” 2021:1). On the other hand, prior to the involvement of Henry in shaping church-state relationship, Martin Luther and John Calvin significantly contributed to this through reformation, which helped many governments to break away from the control of the Pope; forging a new form of church-State relationship with a different texture and form from the former.

Paul III in the 1534 Counter Reformation deployed the military to thwart Protestants. The church remained popular in Europe, but it lost the grip it had on the general populace through management of political affairs of the state. The different reformation agendas and forms; from the protestant reformation through to the catholic reformation, and the English reformation did significantly impact on the relationship between the church and the state.

There emerged a political theology, which continued to remould and reform, not only the church as it were, but the church-state relationship as well. The church from time immemorial has always been regarded as a tool of oppression and often times this has led to the emergence of societal ructions premised along these lines. Religious fanatics even went out of the way to utilise religion as a means to achieve political ends.

The advent of “Holy Wars” commonly known as Jihads in Islam comes to the fore in this regard. Thus, religion emerged as a tool that could be, apparently, employed as an instrument to subjugate fellow humans.

This subjugation is not only about one religion trying to dominate the other, as is the case in Nigeria where Christians and Moslems engage in turf wars, but has also manifested in objectification of women and children whose voices are limited to peripheral roles (Alane Marie Moore, 2011:10).

It does not matter what kind of religion it is, there is a general consensus that the church assumes a patriarchal hierarchy where masculinity dominates all decision-making processes. This has led to deprivation of basic human rights, especially for women and children in religious settings.

Johanne Marange

The JMAC, a church based in Zimbabwe, has not been left out of this matrix. According to Musevenzi (2017:3), JMAC’s belief system and doctrine are not conforming to the ever-changing world.

Allegations of the abuse of women and children are prevalent, and the state stands accused of neglecting its legal duty to protect, promote and defend the rights of women and children. This is even though at state level, the Domestic Violence Act was enacted in 2006, while the Ministry of Gender and Women Affairs, the Ministry of Youths, Sport, Culture and Recreation, a Parliamentary Portfolio on Gender and a Gender Commission have been constituted.

The abuse of women and children in AICs in general, and the JMAC in particular, remains on an upward trajectory.

According to statistics released by a local Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO), Helpline, in 2018, 15 000 cases of child abuse were received and 26% of the cases involved sexual abuse of minors, 28% cases were emotional abuse, 18% of cases were of neglect, 7% on forced marriages and 95% involved females (National Research Council, 2018:59).

However, that study only generalised on the abuse of women and children. It did not zero in on sector specific abuse, of which religion is one. Thus, this paper zeroes in on JMAC in order to understand the interface between human rights and religion. A dualistic approach is adopted to gain a more nuanced understanding of the link between theology and human rights discourse.

The trajectory is different from religious scholarship on African initiated churches in that the study is looking at the nature of the relationship between theology and human rights without being judgemental.

Meanwhile,Mbiti (1969:1) characterised Africans as highly religious, a notoriously religious people.

To that end, the religious nature of the African people makes them advertently and inadvertently submissive to the church instead of state authority.

In Zimbabwe the AICs are key variables in the management of the affairs of the state as a reliable voting constituency, elections, succession and political appointments.

The state seems, consequently, to turn a blind eye to some of the human rights violations (Chikwanha, 2009:2) witnessed in this very important constituency. It is, therefore, key to link the current relations between AICs and the state with the nexus between human rights and JMAC theology on women and children.

State sovereignty

The state under the United Nations Right to Protect (UNR2P) doctrine, constitution and the 1684 Treaty of Westphalia, is empowered to ensure that citizens enjoy their full rights by promulgating policies, laws and programmes that promote such rights.

The challenge comes when the state is found to ignore its legal mandate to protect citizens, particularly women and children from religious hegemony.

In the case of church-state relations in Zimbabwe with regard to AICs, the major challenge is on worldview and the “mine is right” perspective. AICs accuse the state of being lost by embracing foreign elements like the human rights, while the state views indigenous churches as holding on to archaic belief systems based on African Traditional Religion (ATR), which seems to be outdated.

The danger is that both believe to be correct and this “mine is right” position has dire consequences on the rights and welfare of disadvantaged members of society such as women and children.

The Government of Zimbabwe has limited a number of freedoms, for example, the right to demonstrate and petition, where the exercise of this right should be done peacefully and in accordance to Section 60 of the Constitution, Amendment number 20 of 2013 (Constitution of Zimbabwe, 2013:185).

However, it did not limit religious rights as if to confirm that churches in Zimbabwe are not a legal persona and that they are immune to the laws of the country. The rights are not just enjoyed, but they must have a corresponding obligation.

Whilst mainline and Pentecostal churches in Zimbabwe castigate state actions on human rights, the AICs “blindly” support the status quo. AICs have emerged to be a very important electoral cog for the ruling Zanu PF party. In as much as the state is vested with the constitutional mandate to institute a Commission of Inquiry; and that Zimbabwe has such entities like the Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission; it is apparently reluctant to investigate AICs over human rights abuses as is not the case with mainline and Pentecostal churches were personalities such as Robert Martin Gumbura was jailed for 40 years for women abuse (Sibanda & Humbe, 2020:1).

Under the general principle of the greater good, rights should be enjoyed without infringing on other people’s rights. Therefore, religious rights enjoyment should not impinge on the rights of women and children.

In line with this thinking, religious doctrines ought to be, intra vires dictates of the constitution, which is the supreme law in Zimbabwe.

In terms of the Zimbabwean laws, churches are expected to register with the state and provide a constitution which guides their beliefs and their administrative operations.

Historically, the church was above the state insofar as the Hebrew canon is concerned. Kings in Old Testament times were appointed by religion through the prophets.

The diminishing and surrendering of ecclesiastical powers over to the state has been demonstrated in Zimbabwe in the midst of church succession battles that are settled in courts of law, which are a third arm of the government.

One such case is that of the JMAC when it failed to resolve its succession dispute after the demise of Johanne Marange (Chitando eds, 2014:15). The matter was determined by the High Court of Zimbabwe clearly demonstrating the supra role of the state over theological matters. This was an abrogation of one of the main teachings of JMAC that no member of the church is allowed to approach secular courts for any form of litigation.

Whilst states have legal autonomy over the religious domain, the situation is different in Africa where citizens are highly spiritual, making it difficult for them to accept dominance of state over religion.

In addition, religion played a critical role in the liberation history of most African states and they owe their independence to religion. The demobilisation process in Africa has in most cases involved spiritual cleansing to avert avenging and war spirits.

There is a dialectical approach in the understanding of the role and position of religion in the management of African lives and livelihoods. It is this understanding which has seen the proliferation of the gospel of prosperity, healing and political leadership. This background is critical in this study in that it helps in the understanding of whether the state can successfully challenge religion in Africa.

Pre-and post-colonial Zimbabwean leadership has always been seeking guidance from religious figures.

Thus, religion has always been playing a key role in the management and shaping of state affairs.

The AICs were amongst key proponents of the Second Chimurenga which culminated into the attainment of independent Zimbabwe. A majority of the AICs leadership got arrested for resisting the colonial authority during the colonial era. It can be argued that it is this political involvement of AIC’s leadership that forged synergies with the Zanu PF party, resulting in the latter turning a blind eye to human rights abuses obtaining in AICs, particularly the JMAC.

Accordingly, Hackett (1980: 216) opined that AICs’ origin has been largely influenced by negative effects of colonialism and the desire to challenge mainstream churches that came simultaneously with colonialism.

In that regard, anything perceived to be aligned to Christian Western civilisation was heavily criticised, including the human rights discourse. AICs are very reluctant to embrace the human rights discourse and practice due to its Western origins.

Hackett further highlighted that at the centre of the AIC’s fundamental belief system is the castigation of orthodox Christian Western values and belief systems (ibid: 207).

Thus, the AICs represent resistance to change, especially if that change implies conforming to Western civilisation. The theologies of most AICs is anti-Western civilisation in its totality, including its health sector, religion, beliefs, teachings and practices, education, and employment, among other things.

The human rights discourse has Western origins which make it difficult to be accepted within the AICs’ fraternity (Nyangweso, 2010:328). Acceptance of Western human rights by AICs has serious ramifications on their founding principles.

Therefore, compelling AICs to follow Western civilisation is tantamount to a clash of civilisations.

About the writer: Dr Mathew Mare is a Zimbabwean academic who holds two bachelor’s degrees, five master’s qualifications and a PhD. He is also doing another PhD and has 12 executive certificates in different fields. Professionally, he is a civil servant and also board member at the National Aids Council of Zimbabwe.

You may like