Opinion

Best practices in elections: Can Zimbabwe meet these in 2023?

Published

3 years agoon

By

NewsHawksSAPES/RAU

Background

Since 2000, and to some extent prior to 2000, Zimbabwe has a history of disputed elections.

The consequences for the country since 2000 have been dire, leading to the imposition of sanctions and targeted restrictions on individuals and companies, and exacerbating the complexities created by the withdrawal of financial support by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in the late 1990s.

Unacceptable elections have led to a crisis of legitimacy for the government, ameliorated to a small extent with the Global Political Agreement in 2008 and during the period of the Inclusive Government between 2009 and 2013.

Elections were not the only precipitant for international opprobrium. The violations of property rights under the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) were also an issue of concern for the international community and the Commonwealth prior to Zimbabwe’s withdrawal. However, elections and human rights – for the two were frequently correlated – remained front and centre of the concerns about the legitimacy of the Zimbabwe state.

These concerns led to a brief period of euphoria in the immediate aftermath of the coup in 2017, and the ascension of Emmerson Mnangagwa, as the head of the “Third Republic” and a “New Dispensation”. This euphoria dissipated quickly with yet another disputed election in 2018, the violence that re-emerged on the streets in 2018 after the elections, as well as the violence that was meted out to protestors in the demonstrations and protests in 2019.

Since 2018, Zimbabwe, and Zimbabweans citizens, has experienced a continual slide in the economy, the collapsing of public goods and services, rampant food insecurity – not only in the rural areas – and growing evidence of massive corruption by elite groups in the country.

Zimbabwe is now the most politically polarised country out of 34 African countries and receives negative evaluations on virtually every indicator of country performance.

Thus, the stakes for this forthcoming election are higher than at any point since 2000, and the extent of the needed reforms are enormous. How enormous can be gathered by the comment from Dr Akinwumi A. Adesina, president of the African Development Bank Group, at the recently concluded conference on moves to alleviate the country’s debt crisis:

“The governance working group would allow us to tackle and make measurable progress on critical issues of freedom of speech, human rights protection, and implementation of laws in line with the constitution, as well as the implementation of the Motlanthe commission of inquiry and compensation of victims. And we must show progress on the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (Zidera). All of which should make for peaceful, free, and fair elections. They will also remove headwinds on our path to arrears clearance and debt resolution.”

The big question raised by these remarks lies in the conditions perceived to be necessary for peaceful, free, and fair elections. Are these pre-conditions in place for 2023? Can these elections remove the headwinds?

This was the question addressed in an audit of the pre-election climate, and in nine Policy Dialogues held by the Sapes Trust and the Research and Advocacy Unit (Rau). Beginning last year, in August 2022, the series has examined all aspects of the pre-election climate, and this report on the series provides the overall conclusions. A wide range of experts — Zimbabwean, regional, and international — were invited to share their views; the Dialogues were recorded, posted on YouTube, transcribed, and Policy Briefs on each Dialogue produced.

Auditing the Pre-Election Process

The notion of undertaking a pre-election audit of Zimbabwe’s fitness to hold elections began in 2021 with a Sapes Policy Dialogue in November 2021. Dr Daniel Callingaert, an international expert on elections, outlined in his keynote presentation the ways in which authoritarian states undermine elections. Based on his authoritative analysis in 2006, he outlined the many ways in which rigging can take place, the so-called constructive rigging as termed by Jonathan Moyo. By contrast, there is too often an overweening emphasis on anticipatory rigging – the use of violence, intimidation, threats, hate speech, clientelism, etc.– in Zimbabwean elections, not because this is unimportant, but largely because these are electoral violations that are considerably easier to document than the more invisible forms of manipulation.

This has in the past, apart from 2002 and 2008, meant that an election in Zimbabwe is judged on very narrow criteria, and the extent to which the violence was likely to overturn the scale of the victory. For example, without any evidence that the result itself is the product of manipulation, and in the context of a massive victory for Zanu PF, as was the case in 2005 and 2013, demonstrations that there was extensive violence, intimidation, and treating raise concerns but these are deemed insufficient to require rejecting the result. Furthermore, when election petitions are not dealt with in an impartial manner, by delaying them until they are no longer relevant – as was the case in 2000 and 2002 – or dealing with them in an excessively peremptory fashion – as was seen in 2016 – then the probability of deciding whether an election has meet international best practice becomes remote.

However, many of the signs of an election going wrong are evident long before the poll and a thorough going audit can raise the bar on the acceptance of an election. This was the purpose of these policy dialogues: bringing international and domestic experts together to examine what Andreas Schedler has called the Menu of Manipulation.

The series began with the provision of very useful framework for the audit. Outlined by Dr Phillan Zamchiya, this framework consists of five main pillars, within which every aspect of electoral process could be tested for its adequacy, both technical and political, and conclusions reached about the stability of the overall structure and process of the election.

The five pillars are described below, and then examined against the evidence provided to the Policy Dialogues.

The five pillars

At the outset it must be noted that all the five pillars are not separate, but overlap in one respect or another, as well as being an integrated system: the absence of any single pillar will provide the basis for a claiming a flawed election.

Information

This pillar refers to the ability of citizens to obtain all kinds of information, and not merely the openness of the media to reflecting the multiple perspectives of the electoral contestants.

Here it is evident that the partisan nature of the state press and media is a major limitation on the ability of Zimbabwean citizens to hear and understand what the various political parties are offering for governing the country. This has been an endless complaint from multiple observer missions, opposition political parties, and citizens generally, and has been a continual recommendation by international observer groups.

It also refers to the ability of citizens to engage with politicians and attend meetings and rallies without fear and constraint. The banning of meetings and rallies of the Citizens’ Coalition for Change (CCC) is an obvious (and recurrent) feature of the Zimbabwean electoral landscape. This links directly to the second pillar, Inclusion. The issue being addressed here is the extent to which the basic freedoms are present for citizens in the pre-election period: speech, assembly, and association.

Inclusion

Inclusion refers to the notion that elections are about free and equal participation in the electoral process. It refers to the ability of citizens to register as voters, to obtain information (directly and indirectly), to be free from intimidation and violence, and for all forms of treating to be absent.

Inclusion has been a major problem over the past two decades, as well as in past decades since independence, let alone the denial of the vote to most Zimbabweans in the colonial era.

Dr Zamchiya pointed out that denial of inclusion has been growing since the election process gathered steam. Organised violence and torture (OVT) has been increasing since January 2022, with Zanu PF supporters and the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) responsible for 78% of the alleged violations, and opposition political parties responsible for less than 2% of documented violations.

There is also the technical issue around Delimitation and the process of ensuring that every constituency and ward has balanced numbers so that all citizens are ensured equal opportunity and gerrymandering is prevented.

The major issue being addressed here is at the heart of most previous elections: the extent to which political violence, intimidation, hate speech, etc. are present in this current pre-election period. The overlap with Information is obvious.

Insulation

Insulation refers to both the ability to freely register as a voter and to freely vote, which have been problems in most elections in the past two decades. Currently, there are problems in registering as voters, with indications that the numbers registering are low. This is partly due to the perception that elections are never free and fair, and the difficulty in obtaining identity documents, the prerequisite for registering. The ability to obtain an identity document is a major problem as this lies outside the control of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec).

However, the impediments to registering were alleviated in 2013, mostly through lifting the requirement to prove residence by affidavit.

Freely voting is another matter, and the occasion where Inclusion is most strongly affected by intimation and violence, most particularly in the rural areas. Here the partisan role of traditional leaders is a serious problem, and the frank disregard of the Constitution by traditional leaders to be non-partisan a matter of continuous concern over the past 23 years.

It is evident again that there is overlap with Inclusion, and here the major issue is the adherence to the constitutional requirements in section 155 that citizens can exercise their rights in elections:

(2) The State must take all appropriate measures, including legislative measures, to ensure that effect is given to the principles set out in subsection (1) and, in particular, must—

(a) ensure that all eligible citizens, that is to say the citizens qualified under the Fourth Schedule, are registered as voters;

(b) ensure that every citizen who is eligible to vote in an election or referendum has an opportunity to cast a vote, and must facilitate voting by persons with disabilities or special needs;

4. Integrity

Integrity refers to the impartiality and accountability of the election management body, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec). There are many signs that Zec is not impartial as is required by the Constitution, including the significant numbers of military personnel working in the institution. However, it is not merely Zec that must be impartial in the electoral process: all government agencies must be impartial, and this is doubtful in the aftermath of the coup. The Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) and the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) must be firmly under civilian control and politically impartial as required by the Constitution.

Integrity requires all institutions to evince impartiality and accountability through the entire electoral cycle, covering all the antecedent conditions for the vote, the counting and reporting of the outcome, and through to the transparent and impartial dealing with disputes by the courts.

Here the impartiality of the election management body is addressed, and obviously this, or the lack of it, has a crucial effect on the outcome of elections, and the conformity with regional and international best practices.

5. Irreversibility

Irreversibility refers to several things. Firstly, that there is no reversing or tampering with results: the count and the outcome must reflect the will of the people. Secondly, it refers to the acceptance of the results by the loser. Here the outcome of the 2008 elections remains a dramatic example of non-irreversibility; where there was a result indicating that political power had shifted; where even the narrow victory of the MDC should have been graciously accepted (and supported by the region and the continent); but a violent second round resulted in the repudiation of the popular vote. To this might be added the spurious recall of the MDC MPs elected in 2018, and the disenfranchisement of nearly one million voters.

Irreversibility also deals with the judicial process in the management of disputes; effectively the extent to which the courts, both lower and higher, are wholly independent in dealing with disputes. Here the history of dispute management since 2000 is not reassuring, and the preelection audit looks at whether things have changed ahead of 2023.

The initial conclusions from this presentation in August 2022 of the five Pillars, and a preliminary assessment, were not reassuring. The two discussants pointed to the numerous recommendations, by both local and international observers, following the 2018 elections.

Zimbabwean civil society, and especially the ERC and ZESN, immediately began the process of trying to get the government and Zec to address the many gaps in the electoral process, particularly the alignment of the Electoral Act with the requirements of the Constitution.

Draft Bills have been prepared, but these have made very little progress, and with only seven months before elections in 2023, this became critically urgent. The reform process will have significant effect in improving Integrity.

There were also extensive inputs of a range of issues that significantly affect the five pillars, and raised in August 2022:

• The lack of independence in Zec remains a significant concern.

• Voter registration remains a concern, both because of the low uptake by citizens and the difficulties in getting identity documents.

• The non-availability of the voters’ roll, and the impeding of independent audits

remains a problem as in the past.

• Voter education remains constrained and unduly controlled.

• The extreme political polarisation in Zimbabwe creates unfavourable political tensions for the holding of peaceful elections, as well as making the likelihood of a level playing field remote.

So, using these five Pillars, the Election Policy Dialogue series undertook a further eight virtual discussions, and this report provides a summary of the major points made during the discussions and the conclusions reached. The topics covered are provided in Appendix 2.

Assessment of the five pillars

As pointed out above, the data for this assessment is based on the transcribed expert views of the presenters and discussants to the nine Policy Dialogues, which were briefly summarised in nine Policy Briefs.

Information

Information has two important aspects. Firstly, the provision of accurate news and analysis to the general citizenry, and obviously the ability of those in the press and media to investigate and report on elections. Multiple recommendations have been made by domestic and international observers about the need to ensure a non-partisan state-owned press and media.

After all, the state press and media are paid for by the citizenry, and hence should be open to including all. This has not happened as was pointed out by many speakers, but, of even greater concern, was the pointing out the degree to which journalists self-censor out of fear, and the risks in reporting and attending public meetings. It was evident from the discussions that the freedoms of expression, movement, and association are severely restricted for the independent press and media.

The equally important aspect of Information, that of the citizens’ participation in elections, is also a matter of deep concern. Citizens have a right to freely attend meetings and rallies without fear, but it is evident that this is not possible presently, as meetings of the CCC are banned or disrupted, sometimes violently. The levels of hate speech, and the casting of opposition political parties as enemies precludes the notion that this is a competition to persuade the citizenry which party has the best policies to govern the country and meet their aspirations. It is replaced, as all pointed out, by a process that bears a greater resemblance to war than elections, and small wonder that citizens both fear elections and elect not to participate other than by voting.

Information has also been impeded by the process over the passing of the Private Voluntary Organisations Bill, and the disruption of normal civic activities in anticipation of the civic space been severely curtailed. The most serious implication of the PVO Act will be its effect on domestic observation of elections and the inhibiting of independent collection of data – especially about the counting of votes – about the election. The regulatory framework being proposed for registration is so burdensome that none of the domestic observer groups will be able to deploy observers in any meaningful way, and this will have a powerful knock-on effect on international observation.

Quite clearly the conditions for Information being an effective Pillar for a bona fide election are wholly absent.

Inclusion

The issues around Inclusion were front and centre in every discussion, beginning with an assessment of the by-elections held in March 2022. From the beginning in August 2022, the participants were very clear that several key impediments to inclusion were already evident:

• The impunity of state institutions.

• The partisan behaviour of traditional leaders.

• The partisan nature of institutions, such as the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP),

that should be tasked with ensuring Inclusion and Insulation.

• The role of youth militia.

These concerns were repeatedly raised, and not only in the two Dialogues that explicitly examined political violence. Political violence, and all the other methods of inhibiting free participation in elections – intimidation, hate speech, partisan access to resources, and judicial harassment – were all flagged as continuing, and in the most recent Dialogue, February 2023, the participants were unanimous that this was all worsening. They were all deeply concerned about the partisan behaviour of traditional leaders, and the frank statements by traditional leaders about support for Zanu PF in flagrant violation of the Constitution.

A particular point was made in several Dialogues about the President of the Council of Chiefs, Fortune Charumbira, has remained obstinately (and publicly) partisan, despite being in contempt of a court order, emphasising all the concerns about impunity. Most recently, there the statement by the former Vice-President, Kembo Mohadi, clearly in violation of the Constitution, that villagers would be “frog marched” to vote for Zanu PF.

The complaints about traditional leaders bolster the views about impunity as the Constitution is clear in Section 281(2) of the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 20) Act 2013 “(2) Traditional leaders must not- (a) be members of any political party or in any way participate in partisan politics; (b) act in a partisan manner (c) further the interests of any political party or cause; or (d) violate the fundamental rights and freedoms of any persons.”

The most startling input on the impediments to Inclusion came from speaker in the second Dialogue on political violence: it was startling because it came from a former member of Zanu PF. As Dr Shumba pointed out:

“Now, crucial to understand the issue of violence is to understand the systems that are deployed by Zanu PF during elections and just before the election process.

There is active intelligence work that takes place in identifying potential opponents to disable them, strengthen them, weaken them, and ensure that they do not even have the resources to participate. If we tend to just look at the violence in terms of the physical beatings, killings, and so forth, we will be focusing on a major segment of it or meeting the other work of violence that is committed by Zanu PF, by the police, by the intelligence, and the military. We may not physically identify these people because they don’t do it in their regalia or uniforms, they get embedded in the systems structures of Zanu PF: more particularly the military, they work with the commissariat department to identify and discipline those of other views”.

This assessment of the degree to which citizens are excluded through political violence in all its manifestations was repeatedly endorsed and amplified by multiple examples throughout the series.

It can be quite simply concluded that, when it comes to Inclusion, no such thing exists for the Zimbabwean citizen who holds any different views from Zanu PF and will face considerable threat in exercising his or her freedoms in participating in elections.

Insulation

Insulation is yet another key Pillar and has extensive overlap with Inclusion. As with the latter, Insulation applies across the whole electoral process, right to the process of voting and counting the votes. Critical to Insulation is the ability of citizens to both register and cast their votes. The former has been an enormous problem in the past, but, since 2013, the tedious and discriminatory procedures have lifted. However, as is pointed out in more detail in the section on Integrity, the right to register has been impeded by the difficulty in getting the requisite identity documents necessary for registration as a voter. This has shifted the bureaucratic burden from one state agency to another, but the effect is the same. There were several comments that there was discrimination in favour of rural residents in getting access to identity documents and registering as voters.

The actual process of voting is rarely impeded in elections, and, not since 2002, have there been reports of political violence on the polling day. However, it is evident that actual voting depends on easy access to polling stations, and here there have been continuous complaints about the allocation of polling stations between rural and urban areas, and often the very long delays for urban voters. Of course, the many points made by the discussants throughout the webinar series about the inhibitory effects of political violence in all its forms indicate that voting can be affected way ahead of the actual poll: what is called “anticipatory” rigging.

It is important to pay careful attention to the counting because a lack of transparent counting leads to easy allegations that this is rigged. In the discussions around the Kenyan elections, it was important to learn that organisations, the press, and media were able to release results as they came in, and, whilst this led to some controversy, it was also evident that this also cooled the temperature.

Problems over counting have occurred in past Zimbabwean elections, most dramatically in 2008, and there have always been allegations about bias in counting. The most recent election in 2018 raised the problems again, and as covered in comprehensive detail in ExcelGate, the shenanigans over resorting to counting the V11 returns as opposed to the mere calculation of the V23 returns, only 10 forms. This was inadequately dealt with in the election petition process in the Constitutional Court, and, as pointed out in ExcelGate, the flagrant violation of the Electoral Act (Chapter 2:13) by Zec of the legal requirements for the transmission of results. The point about the subversion of the counting process in 2018 was raised by one of the discussants, making the point about the inadequate treatment of this very important case by the Constitutional Court.

Perhaps the biggest issue when it comes to Insulation is the need to improve the transparency of the counting process and remove the insistence that only Zec is entitled to publish results.

In most countries, results are released as they come in, and this, in Zimbabwe, comes when the V11 is signed off at a polling station by all the relevant parties and is posted outside the polling station. Since this is now public – and legally public – there can be no possible reason that political parties, civic organisations, and the press should be entitled to collate these

results and publish the results themselves. This avoids accusations about rigging, creates confidence in the electoral management body, and increases the likelihood that losing parties will accept the outcome; in fact, such a process frequently leads to political parties and candidates conceding elections, even before the final results are available, since the evidence of loss is apparent to all. The comparison with Kenya in its last election showed how how different can be the process.

It is evident from all the discussions that there are significant problems with insulation and that none of these have been sufficiently addressed. As was pointed out by one presenter, there is little evidence that the recommendations by local and international observers have been taken on board by either Zec or the government. This raises the important role of election observation.

The importance of election observation emerged throughout the Dialogues but given special attention in one Dialogue. Of importance was the role assigned to observation given by organisations such as the African Union and Sadc, but also by most reputable observer groups, all of which have comprehensive procedures for observation. However, it was pointed out repeatedly that the role of domestic observers is crucial for the effectiveness of outside observers since few of the latter can provide the breadth of cover or the extended time that can domestic observers. In this regard, frequent comment was made about the probability that the Private Voluntary Organisations Act will seriously impede domestic observation through the burdensome conditions imposed on NGOs. With weak and handicapped domestic observation, international observation will become weaker too. A serious question here is whether international observation should take place at all if it is evident that there can be no credible domestic process.

Integrity

Integrity, as briefly explained above, mostly refers to the conduct of the electoral management body, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec). The lack of Integrity of Zec was raised continuously in the Dialogues. It was a major concern from the very first Dialogue in August 2022, as the discussants pointed out the following:

• The lack of independence in Zec remains a significant concern. There were frequent references to the apparently partisan affiliation of some of the commissioners, and to the presence of staff who have unclear affiliation to the military.

• Voter registration remains a concern, both because of the low uptake by citizens and the difficulties in getting identity documents.

• The non-availability of the voters’ roll, and the impeding of independent audits remains a problem as in the past.

• Voter education remains constrained and unduly controlled.

It was evident in the subsequent Dialogues that little had changed in the following eight months. Whilst there was rhetoric from Zec about increasing voters’ registration, no-one in the Dialogues was in agreement. The continual perspective was that Zec was partisan and unaccountable. Concerns were raised about the composition of Zec, its lack of transparency and accountability, the continued bias in registration, and the issues around the accessing and independent auditing of the voters’ roll.

As for registration itself, it was evident that the major impediment to registration lies in the difficulties in obtaining identity documents. Although not under the control of Zec, access to IDs is under the control of the government through the Office of the Registrar-General, and there is little evidence that this office is making a strong effort to ensure that citizens are able to register through making such access easy. There is the recent disclosure that 21% of the youth do not have IDs. According to the Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency (ZimStat), 951 994 young persons between the ages of 16 and 34 years do not have IDs.16 A responsible electoral management body would provide extreme pressure, through the government, on the Registrar-General’s office to ensure that the requirements of the Constitution – that it made be made easy to register in order to vote – were complied with.

The biggest complaints about the Integrity of Zec emerged in the two examinations of delimitation. In the first Dialogue in October 2022, and the comparison with Kenya, the best practices for delimitation were canvassed, and an expert keynote presentation by Staffan Darnolf outlined the basis upon which Kenya has approached this. The Kenyan process was based on five principles:

1. Impartiality: The boundary authority should be a nonpartisan, independent, and professional body.

2. Equality: The populations of constituencies should be as equal as possible to provide voters with equality of voting strength.

3. Representativeness: Constituencies should be drawn taking into account cohesive communities, defined by such factors as administrative boundaries, geographic features, and communities of interest.

4. Non-discrimination: The delimitation process should be devoid of electoral boundary manipulation that discriminates against voters on account of race, colour, language, religion, or related status; and

5. Transparency: The delimitation process should as transparent and accessible to the public as possible.

The Zimbabwean discussants were deeply pessimistic that Zec would come close to approximating these principles in its delimitation, and so it proved. By the second Dialogue on delimitation in January 2023, and the publication of the preliminary delimitation report by Zec, it was evident that the process was in shambles.18 Apart from the complete absence of transparency, it seemed obvious that every other principle had been ignored. For example, when it comes to equality, and the Constitutional requirement that all constituencies be equal, and only vary by 20% overall from the national average, Zec had interpreted this to mean 20% above and below, resulting in 40% variance from the national average. It was likely that the process has violated the Constitution, as has been pointed out by Veritas – both during the Dialogue and subsequently.

The ensuing furore over the delimitation led to a majority (7) of the Zec commissioners refusing to sign the report – a dismal prospect for an election management body about to run a national election – and a court challenge on the report. It is instructive, and highly relevant to the pillar on Irreversibility, that the legal challenge was dismissed by a full bench of the

Constitutional Court without a full judgement.20 This evokes for many the decision by Justice Hlatshwayo on the electoral petition on the 2002 Presidential election: application dismissed, judgement to follow, and never a judgement seen to date. It will be instructive to see whether this judgement of the Constitutional Court emerges before the poll later this year, or only after when it will have no effect on the poll. It should be noted, however, that a second case is being entertained by the court on the same issue, and it will be important to see whether this application receives the same treatment or not.

There were repeated concerns over the lack of access to the voters’ roll, and the claims by Zec that this was to prevent manipulation of the roll. This spurious argument was based on fears about hacking but ignored the obvious issue: the content of the roll is under full control of Zec, any audit could only use the roll provided, and no audit of the roll could alter details held on Zec’s computers that are presumably secure against hacking. Since a copy has been leaked and shows multiple errors – as Team Pachedu has shown – this only raises concerns about the veracity of the roll and raises all the concerns that were seen in previous audits on the 2008 and 2013 rolls.

Thus, it seems evident on all the available evidence, and the views of the experts consulted,

that Zec wholly fails the test of Integrity, and in its seriously divided state, there can be no confidence that it can run an election that meets the test of best practices.

Irreversibility

In no election since 2000 has the losing party accepted the result, and for every election, opposition parties and candidates have sought relief from the courts. Thus, in a climate when there is little confidence in the election process, elections are frequently violent, and the whole counting process is completely opaque, it can almost be guaranteed that the courts will have a crucial role in elections. Above there is brief reference to this already taking place, and the Constitutional Court dismissing a potentially critical complaint about delimitation without giving a judgement on the merits of the case.

During the Policy Dialogues, a contrast was made between Kenya and Zimbabwe over election petitions. It was evident from the reports of Zimbabweans, who observed the recent Kenyan elections, that one serious improvement in Kenya was that the court now had the complete confidence of the citizenry. In the opinion of former Chief Justice, Willy Mutunga, this was due in part to the new Kenyan Constitution, but also to the more assertive role the courts had adopted in dealing with issues related to elections, as well as much greater transparency by the courts. Additionally, there had been a serious “cleansing” of the judiciary after 2007. The result was that a comprehensive analysis on the election – and dealing with the conflict within the election management body – ensured that the outcome was acceptable to all, even the losing candidate. However, as was pointed out by Willy Mutunga , losing parties will always dispute the outcome, even if only politically, as such dispute is linked to maintaining the support base of the losing party.

By contrast, Irreversibility in Zimbabwe has been wholly unsatisfactory. Two trends have been observed. The first is the delaying of proceedings such that the petition falls away due to passage of time, as was the case with all the thirty odd petitions brought after the 2000 parliamentary elections. The effect of the delay was that all the candidates challenged completed their term of office in 2005.23 A similar delay was experienced for the Presidential poll in 2002, but this judicial process also demonstrated a second failing by the courts, that of dismissing the first part of the petition – crucial constitutional irregularities – without a subsequent judgement. In fact, the judgement has never been delivered. The petition in 2018 met a similar fate: that of an abbreviated process that did not allow comprehensive discussion of critical issues, particularly the matter of Zec reverting to the V11 data and ignoring the legal chain of election result compilation. This was described in considerable detail in ExcelGate. Since there is no appeal from the decision of the Constitutional Court in election petitions, the alleged violations of the Constitution and the Electoral Act become irrelevant and there is no pressure for reform of Zec.

A further example of delaying legal process such that the cause of action falls away comes with the decision over the unconstitutional appointment of five extra ministers in 2009. This was challenged in the courts, the application dismissed, appealed, but never completed before the end of the Inclusive Government in 2013.

As for the role of the courts in mediating disputes in the pre-election period, there was concern over the abuses around bail, with Job Sikhala being the most egregious example, and the acceptance by the judicial process of the contempt by Fortune Charumbira. All of this suggests that there can be little confidence in a non-partisan role by the courts over elections and creates the strong probability that strict adherence to constitutionalism and the rule of law cannot be expected.

Conclusions

A key issue in any audit of the pre-election processes is the extent to which the process looks like it is conforming to best practices. Here there are two guidelines that should be directing the preparation for elections: the Sadc Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections and the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance of the African Union. We do not attempt any formal assessment of Zimbabwe’s conformity with these standards, but rather draw some conclusions from the comparisons made between Kenya and Zimbabwe, as well as conclusions drawn from the analyses provided by the experts, largely based on their assessment of compliance with Zimbabwe’s own standards, the Constitution, and the Electoral Act.

A major point in the final discussion was over the publication of results and the final authority of Zec in publishing results. The point was made that once the count has taken place, the returning officer and the party representatives have agreed on the result, and the V11 form is posted outside the polling station, should the general public, the press, and observers not be entitled to collect and collate results as they come in? This is common practice in many countries, and, as pointed out in one Dialogue, occurred in Kenya. There was disagreement over the desirability of independent collating and reporting on results. One view was that this is desirable and leads to greater confidence in the electoral process, whilst the contrary view was that this will lead to dispute and be left only to Zec.

An additional point raised was the lack of a transitional mechanism in finalising the election and the establishing the government, as is increasingly the case in many countries. This describes a set of legal procedures to be followed after the final count, and not merely declaring the winner and swearing in the president.

Comparison with Best Practices

Some of the most telling conclusions came from a comparison on best practices emerging from contrasting Zimbabwe with Kenya, two countries that have experienced violent and repudiated elections in the past and having to put in place coalition governments to reform ahead of the next elections. This was covered in three of the Dialogues.

The first examined the recently completed (2022) Kenyan elections with the just-completed by-elections in Zimbabwe. The presenter and the discussants – all Zimbabwean – who had observed both elections were in no doubt that Kenya has shown great improvement on every one of the Pillars. Issues around the independence of the electoral management body, the dealing with electoral disputes in the pre-election period, the role of the press and media, and the transparency of counting were highlighted with approval of the Kenyan process and criticised in Zimbabwe.

The second examined the role of the courts in Kenya and Zimbabwe in dealing with electoral disputes, and particularly the contrast between the Kenyan Supreme Court and the Constitutional and Supreme Court in Zimbabwe. This contrasted the careful process of amending the constitution in Kenya, and the careful (and successful) treatment of the dispute over the Kenyan Presidential poll in 2022.

Crucially, it was evident that the Kenyan reform process has resulted in the creation of deep trust in the courts by the citizens in Kenya. By contrast, the detailing of the Zimbabwean courts’ treatment of electoral disputes was shown to be woefully lacking in any evidence of impartiality or credible attention to the importance of electoral disputes. It was also worth noting that the decision by the Kenyan Supreme Court resulted in the losing candidate accepting the result of the poll, thus obviating claims about the illegitimacy of the government and creating political instability.

The third was the examination of the delimitation processes in Kenya and Zimbabwe, and the demonstration of how seriously Kenya has addressed this, setting up clear principles for delimitation and providing the confidence in the electorate and political parties that no room for gerrymandering was possible. The discussants were less complimentary about the Zimbabwean process, and even less so in the second discussion after the draft delimitation report has been release by Zec in February 2023.

Fourthly, it was evident throughout that there were multiple concerns about the transparency and accountability of Zec, and how this has led to a widespread lack of confidence in Zec.

This was amplified by the demonstration that a very large number of recommendations were made by domestic and international observers – by one estimate 115 of these – with some very crucial reforms required:

• Ensuring complete independence of Zec from government oversight.

• Complete alignment of the Electoral act with the Constitution.

• Control of assisted voting, as this was still evident in by-elections in 2022 –

between 10% to 15% of voters were “assisted”.

• The role of the state media and press.

• Ensuring the non-partisan status of traditional leaders, which now is getting worse not better.

Thus, it seems fair to conclude that Zimbabwe, as in the past, falls way short of regional and continental best practices, and it does not require this judgement to made at the end of the poll. Here it should be remembered that the National Democratic Institute (NDI) was pilloried in 2000 for producing a pre-election report and alleging that the election could not be free or fair. The criticism was that this was a precipitate assessment, but subsequently the Commonwealth and others came to the same conclusion after the poll, so the NDI prediction was not off the mark.

Is Zimbabwe ready for elections?

The short answer is that this audit suggests that there cannot be any confidence in the forthcoming elections. The conclusions for each of the pillars is that there are severe deficits for each and every one of these, and the examination of how each pillar reinforces each other amplified this. In many ways, the pre-election process looks worse than it did in 2018, and many forms of bad electoral practices not seen in the past two elections – in 2013 and 2018 – have returned with memories of the very bad elections in 2000, 2002, and 2008.

Primary amongst these is the rising political violence and the association with groups supporting the campaign for the presidency, as well as increasing reports of militia groups operating. This is all linked to intimidation, forced membership of Zanu PF, and clientilism on a massive scale. Unlike 2018, opposition political parties, and mainly the CCC, are having rallies banned, even having meetings in private houses disrupted, attendees arrested, and even lawyers assaulted. The levels of hate speech have increased, some of which are so egregious that they warrant arrest and prosecution. There is harassment and legal intimidation of political opponents, with one member being charged and found guilty of a non-existent law.

The blatant partisanship of traditional leaders is yet another negative indicator.

It is also a matter of extreme concern that so few of the youth have been able to register as voters: that one in four do not have identity documents that would enable them to register and vote is a serious matter. Whether this is due to the difficulties in obtaining documents or is added to by the total lack of political trust by the youth, it still raises that problem about the legitimacy of the government to be elected. The narrow, legalistic approach by the government and Zec to elections does nothing for establishing legitimacy. This flows from the consent of the governed, not from the narrow determination that the rules were followed in a parsimonious fashion: elected governments establish their legitimacy through the demonstration from the widest possible participation in voting, not just that they obtained a majority.

Legitimacy also flows from the demonstration that the game was fair, the referee was nonpartisan, and the outcome can be validated by impartial scrutiny. None of this is present in 2023, and the only prediction that can be made is the result once again will fail the test of acceptability, both nationally and internationally. Furthermore, the intention to produce a “landslide” victory for Zanu PF will fail also the test of credibility since none of the conditions that are a pre-requisite for a free and fair election are present now, and there is no possibility that all the desperately needed reforms are possible in the next three months.

When the Election Policy Dialogue series began last year there were possibly 10 months in which reforms could have been undertaken, but this is no longer possible.

This pre-election audit indicates that the conditions for a free and fair election are absent, and there is little possibility that the multiple reforms necessary can be achieved in the little time remaining. Thus, the kinds of recommendations that can be made must focus on what must be

done to deal with a flawed election. There seems little doubt now, with the decision by the Constitutional Court dismissing the application to set aside the delimitation,25 that elections will take place, underlining the concerns raised in the Elections Policy Dialogue about all the secrecy around setting the date for the elections this year.

If the hopes that an election can cure the coup and restore the country to legitimacy and international re-engagement cannot be met, then the focus must shift to a more political process, and one in which the international community – regional, continental, and international – must play a significant part. The consequences for Zimbabwe and the region are too serious for it to be business as usual following another failed Zimbabwean election: as pointed out elsewhere, Zimbabwe has reached its “Lancaster” moment.

The desperate citizens deserve better than more form without content, and a serious intervention to lift them from increasing penury and hardship.

About the writers:

Sapes Trust is an independent organisation that seeks to nurture social science research, teaching, policy dialogue, networking and publications in the southern African region and beyond, through specific programmes, but with the deliberate intent to impact on policy and assist in the sustainable development of the region.

The Research and Advocacy Unit (Rau) is an independent non-governmental organisation whose mission is: “To conduct research on human rights and governance issues, particularly those pertaining to women, children and State institutions, with a view to bringing about policy changes which promote a democratic culture within Zimbabwe”.–Rau.

You may like

-

‘Chamisa must introspect, map the way forward’

-

By-elections lacked credibility

-

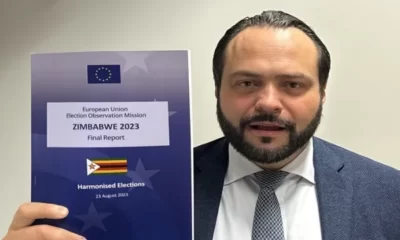

EU observer mission report nails Zec

-

Sadc’s election report leaves Mnangagwa desperately out in the cold with only one option — reform

-

Polls lacked credibility: Carter Centre

-

Mnangagwa inauguration under a dark cloud of illegitimacy