Opinion

A tale of broken promises: Zimbabwe after Mugabe

Published

4 years agoon

By

NewsHawksSIPHOSAMI MALUNGA

FOR millions of Zimbabweans, who had suffered political repression and economic deprivation and decline during the preceding 40 years, Mugabe’s removal was a much-needed relief.

Little did it matter that it was his comrades, with whom he had killed thousands, stifled dissent, closed the democratic space and plundered the economy and public purse who removed him, under the banner of the ironically titled Operation Restore Legacy.

He was the head of the Zanu PF system, and as such, his exit was seen by many as providing an opportunity for change.

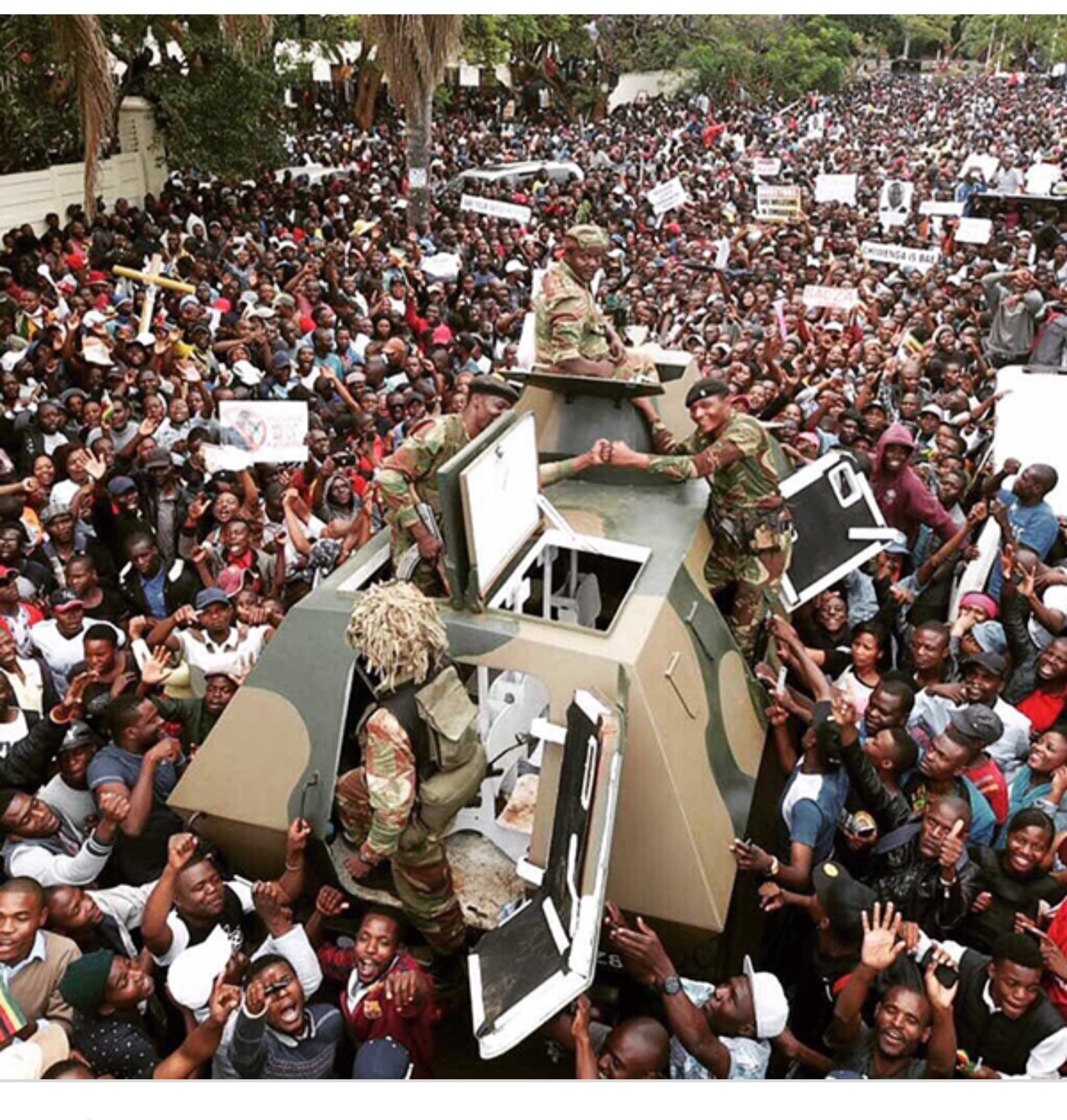

For that reason, rallied by the army generals who were seeking but struggling to “constitutionally” remove Mugabe, thousands of Zimbabweans came out to the streets to send a message to Mugabe “to leave and leave now”. Thus, they “sanitised” the coup.

After his removal, the generals summoned Mugabe’s former deputy,

Emmerson Mnangagwa, back from exile to take over. Mnangagwa had dramatically fed the country weeks earlier after being fred by Mugabe, claiming that he feared for his life after an alleged poisoning attempt.

After taking control of the ruling party and reversing all of Mugabe’s decisions and dismissals that had affected Mnagangwa’s faction, the generals took their plan to Parliament, forcing Mugabe to buckle and resign.

Mnangagwa was inaugurated as President on 27 November 2017 with promises to bring in political and economic reforms. At his inauguration, attended by foreign diplomats and opposition leaders, Mnangagwa promised to undo the disastrous results of Mugabe’s 37-year rule.

He promised to fix the ruined economy and open the long isolated and ostracised country for business and investment. He promised to restore and respect democracy, to repeal draconian laws, to restore the rule of law, to fght corruption, to revisit compensation to white farmers for land, to re-engage the international community and most importantly to respect the will and voice of the people, which, he argued was the voice of God.

To that end, he promised to provide the people with the ultimate opportunity to decide on the future political leadership of the country via free, fair and peaceful elections. Individually and taken together, what Mnangagwa promised was exactly what the country needed, and what it had been denied by Mugabe and Zanu PF for decades.

Two years after Mugabe was deposed, with Zimbabweans worse off than they were during the worst of Mugabe’s equally disastrous rule, it is clear that Mnangagwa’s is a tale of broken promises. So what went wrong?

False expectations, false change

To start with, post-Mugabe Zimbabwe was a proverbial house built on sand.

Driven by Mugabe’s henchmen, who had been the architects and implementers of his disastrous policies in the previous four decades, it was not really the change that Zimbabweans and the world thought it would be. It was triggered by and aimed to settle an internal Zanu PF factional fight between the Generation 40 (G40) faction, led by Grace Mugabe, and Lacoste, led by Emmerson Mnangagwa, inside Zanu PF. It was and had never been a people’s project and certainly never ideologically founded or spurred on by a genuine desire for real political and social change.

To that extent, little should have been expected from the coup. This alone easily explains why it delivered nothing in resolving Zimbabwe’s long-term crises and instead dug the country into a deeper hole. The so-called new dispensation has been a catalogue of failure since November 2017, failing the several tests it faced.

Failed political reform

The first test for the post-coup regime was openness to political reform.

Under Mugabe, Zanu PF had shown extreme political intolerance. In the 1980s, seeking a one-party state, Mugabe, with Mnangagwa as his security minister, had massacred thousands of supporters of the opposition Zapu, forcing its leader Joshua Nkomo to capitulate and join a unity government under Zanu PF.

In the 1990s, Mugabe had violently suppressed all signs of internal and external opposition, sending gunmen to shoot and kill opponents in the Zimbabwe Unity Movement. In 2000, his ego dented by the loss of the constitutional referendum, and fearing that he would lose the parliamentary election to the new Movement for Democratic Change (MDC),Mugabe had deployed party youths and war veterans to violently attack white farmers and farm workers perceived to be supporters of the new opposition party.

In 2008, with clear signs of having lost the presidential election to Morgan Tsvangirai in the first round, he resorted first to rigging, then violence, to win the run-off from which Tsvangirai ended up withdrawing.

When Mnangagwa took over in 2017, all eyes were therefore on how his regime would treat the opposition. Never mind that Mnangagwa had been Mugabe’s mastermind and enforcer of violence against the opposition, going back to 1980. As security minister, he had directed the intelligence aspects of the Gukurahundi operation that left 20 000 civilians dead. In 2000, 2002 and 2008, he had also played a key role in election-related violence directed at MDC officials and supporters.

He was considered a key architect of the closed political space in Zimbabwe, an idea that went back decades. To many, it was therefore unreasonable to expect any meaningful change in political tolerance after the coup.

Yet, aware of his own dubious credentials and also to curry favour with his western backers and funders, especially the United Kingdom, Mnangagwa promised to open the country up not just for business but also politically. In a public relations stunt, he publicly visited the ill MDC leader Tsvangirai and offered government support for his medical treatment as well as the transfer of his offcial state-purchased residence, which Mugabe had refused to hand over. He even tolerated criticism in the media and from civil society on historically taboo subjects, such as Gukurahundi. To cap it all, he even “joined” social media.

The period between the coup and elections in July 2018 saw a marked and unprecedented improvement and opening up of political, civic and media space. But purges of G40 elements, Mnangagwa’s erstwhile nemesis, continued, with selective arrests and prosecutions. There were still bans on protests, arbitrary arrests, the abuse of power and authority, and regular violations of constitutional and human rights that targeted activists.

Fixed and flawed elections

The second major test was the general election in July 2018. Seen as being central to restoring democracy after the coup, there was little doubt that the post-coup elections would need to pass the free, fair and peaceful test.

Previous elections in Zimbabwe had been bloody, with outcomes contested. In 2008, because of the violence, the continental and global community had refused to sign off the presidential elections, forcing Mugabe into a coalition government with Morgan Tsvangirai. In the 2013 election, although it had been peaceful, the manipulation of the roll of voters, which was withheld by the electoral commission until election day, again undermined the legitimacy of Mugabe’s victory. In 2018, Mnangagwa was therefore aware that if anything was needed to gain internal and external legitimacy as part of his open for business mantra, delivering free, fair and peaceful elections was the silver bullet.

Despite their promises, Mnangagwa and Zanu PF resorted to tried and tested tactics. They retained the tainted and discredited Zimbabwe Election Commission and secretariat, considered by many as lacking independence and made up of security and intelligence personnel.

Again, as in previous elections, the commission failed to release the voters roll on time and in a searchable format, and even then it was plagued with irregularities. As in previous elections, Zanu PF leaned on the army — whose mere presence, especially in rural areas, intimidated voters. It also manipulated the government’s agricultural subsidy scheme to “buy” the rural vote.

As in previous years, Zanu PF and Mnangagwa monopolised the state media in their electoral campaign, denying equal and fair play to the opposition. With the Mugabe era draconian laws on access to information and protection of privacy, and on public order and security, still frmly intact, the pre-election environment and playing feld was far from being level.

The operational conduct of the election, including the tabulation, transmission and announcement of elections results, pointed to a rigged process. With the closeness of the results between Mnangagwa and his opposition challenger, Nelson Chamisa — with Mnangagwa receiving just over the 50% required — no wonder the outcome was disputed and challenged in court. The Constitutional Court ruled in favour of Mnangagwa but failed to give its reasons for almost 18 months, further entrenching partisan perspectives.

Leopards cannot change their spots

Mnangagwa’s third test involved human rights. As he had played a central role as Mugabe’s right hand, in the gradual and systematic erosion of citizens’ rights for the preceding 40 years, many were sceptical that he and Zanu PF would miraculously begin to respect human rights.

The sceptics were right. Shortly after the July election, in response to public protest against delays in announcing election results, Mnangagwa deployed the military — who shot and killed six unarmed civilians and injured scores more.

These killings, conducted in full view of election observers and international media, cemented the scepticism about any post-Mugabe change by Mnangagwa and Zanu PF. As damage control, Mnangagwa commissioned an international commission of enquiry led by former South African President Kgalema Motlanthe, but it was made up of regime-sympathising local commissioners whose work was carefully choreographed.

In a further clear sign that little had changed, despite recommendations by the Motlanthe commission to hold military offcers to account responsible for the killings, Mnangagwa instead promoted the commander of the unit responsible, while other perpetrators remained untouched.

There would be further failures. In January 2019, when citizens who were angered by the sudden increase in the price of fuel took to the streets, Mnangagwa again deployed the army against them.

What followed was a military operation conducted under cover of an internet shutdown in which grave violations, beatings, torture, rapes and plunder were carried out against innocent civilians. Mnangagwa would later boast that he had deployed the army to deal with protesters after giving instructions to use a “special whip laced in salty water”. After the protests, thousands of civilians were arrested and tried in unfair and fast-tracked trials, while hundreds were sentenced to many years in prison.

Again, in August 2019, with the country and citizens facing dire social and economic conditions, the opposition MDC called for nationwide mass protests. Complying with the public order and security law, it sought police authorisation for the protests, which was denied. On the day, riot police unleashed an orgy of violence against peaceful protesters, beating and arresting many.

Throughout Mnangagwa’s rule, the government has continued to selectively target critics, labour, human rights and political activists for intimidation, harassment, abduction, arrests, detention, torture and killings. In many instances, it has relied on pseudo-elements in the security sector or party youth wings to carry out these heinous crimes.

Fearing an uprising similar to those in Sudan, Egypt and Algeria, the government has resorted to selective abductions of critics who lead or call for citizen action, in order to spread fear and deter citizens from protesting. Most recently, the leader of the striking hospital doctors’ union, Peter Magombeyi, was abducted, detained for fve days, tortured and then dumped in the outskirts of Harare.

The government claimed that a shadowy “third force” was involved. Other critics calling for accountability for Gukurahundi atrocities, including activists such as Zenzele Ndebele, Thandekile Moyo and Mkhululi Hanana, have also been intimidated, followed and threatened by unidentifed individuals.

In an unprecedented surge of intolerance, the government has also resorted to abducting, beating and torturing human rights activists, such as Tendai Mombeyarara of the Citizens Manifesto and Amalgamated Rural Teachers’ Union of Zimbabwe, which is led by Obert Masaraure. Samantha Kureya, “Gonyeti”, a comedian, and Ian Makiwa, “Platinum Prince”, a musician, have also been abducted, beaten and tortured for satirical and musical productions that were deemed infammatory and offensive to Mnangagwa and the regime.

Some have not been so lucky. Blessing Toronga, an MDC political activist, was abducted from his house in Glen Norah Township in Harare by unidentified men after the protests on 24 January 2019. His body was found in an advanced state of decomposition in March this year.

As Mugabe did in the 1980s, Mnangagwa has relied on trumped-up treason charges against perceived critics and opponents.

Victims include Tsvangirai, Welshman Ncube and others in 2000, those involved in the “MDC 17 petrol bomb case” in 2015 and MDC deputy president Tendai Biti in 2008.

In 2019 alone, the government has charged seven civil society activists with treason, continued to prosecute pastor Ivan Mawarire, for Mugabe-era treason charges, and charged several MDC politicians, including Job Sikhala, Joana Mamombe and Gift Ostallos Siziba, with treason. Undoubtedly, on this score Mnangagwa has not only proved sceptics right, but has matched Mugabe in many respects.

Corrupt and predatory elite

The third major test for Mnangagwa and Zanu PF was their policy and attitude to corruption, bad governance and poor leadership. When he took over from Mugabe, Mnangagwa promised to open the country, isolated for many years, for business. He promised to fight corruption and to ensure the rule of law.

Corruption, bad governance and poor leadership have been at the centre of Zimbabwe’s political, economic and social problems for the past 40 years.

Under Mugabe, a politically connected and predatory elite, comprising ruling Zanu PF officials, their families and friends, prioritised the personal accumulation of wealth over public interest and service.

This elite has been involved in high-level corruption scandals since 1980. It has siphoned off billions of dollars, abused public resources and enjoyed impunity from any form of accountability. Almost all Mugabe’s ministers have at one time or another been implicated in corruption.

Mnangagwa’s commitment to addressing corruption, bad governance and poor leadership was therefore in the spotlight. His choice of ministers, his attitude towards corrupt elites and his appointment of capable leadership were objects of scrutiny. In all these aspects, he failed dismally. He appointed and retained corrupt cabinet ministers — some of whom, in yet another public relations stunt, he has now sought to arrest.

He set up an anti-corruption unit in his offce, which has delivered nothing. He has allowed powerful elites connected to him, such as Kudakwashe Tagwirei’s Sakunda, to retain monopolistic control of the country’s lucrative fuel supply contracts. He has allowed the use of the Reserve Bank for preferential access to foreign currency exchange for connected elites, which it expatriates, launders or sells on the black market at a premium in a system of arbitrage. He has allowed the plunder of US$3 billion from the “command agriculture” subsidy scheme, most of which has found its way to Sakunda.

As the country faces a severe public service crisis in the water, energy, health and education sectors, Mnangagwa has presided over declining and deepening social conditions. Poor governance and leadership tied to corruption have seen his ministers preoccupied with lining their pockets and diverting public resources to their personal upkeep and beneft rather than addressing the multiple crises the country faces.

A failed economy

Mnangagwa’s greatest test was the extent to which he would be able to fix Zimbabwe’s ruined economy. His inability to do so has been his most epic failure.

In the main, wages have lost all value and purchasing power owing to the disastrous economic policies of Mthuli Ncube, Mnangagwa’s minister of Finance. Ncube was initially feted as a professor from Oxford and a former African Development Bank chief economist, but he was also previously founder and owner of a failed Zimbabwean bank, Barbican, who has banned the use of foreign currency exchange, reintroduced the discredited Zimbabwe dollar, introduced an extortionate transactional tax on electronic transactions and allowed activities at the Reserve Bank that have been condemned by the International Monetary Fund.

In the past six months of 2020, in the latest budget announcement the Finance minister has been accused of embarrassingly cooking the national accounting books by understating the contributions of China by over US$100 million.

The disastrous economic policies and the accompanying corruption have seen doctors and nurses go on strike for months because of poor wages and working conditions: no hospitals have adequate equipment, medicines or medical supplies. The government response has been to abduct leaders of doctors’ or teachers’ unions and to fire all doctors.

Living conditions have deteriorated for the majority of citizens to levels worse than during the Mugabe era, with power blackouts for days and shortages of fuel, banknotes, medicines and other basic needs. Inflation has shot up in the third quarter of 2020.

In June 2020, the government banned the use of foreign currency, deepening the hardship but proclaiming the return of a robust national currency. In November 2019, the government introduced new bank notes but the release was marred by another corruption scandal in which hundreds of thousands of dollars surfaced on the black market when the maximum permitted withdrawal is $200.

The final test

Mnangagwa’s last test will be whether and how long he can hold on to power in the context of the continuously deteriorating conditions in the country.

There is an overwhelming consensus that the situation seems to have reached breaking point. Whatever the plan for removing Mugabe may have been for the coup comrades, it is hard to imagine that this is what was agreed or expected. It is possible that the plotters collectively underestimated what was required to fix Zimbabwe. They assumed that they could continue to fudge their way forward by crushing dissent, stealing elections, printing money, recklessly spending state funds and plundering the economy without consequence. If that is the case, they were wrong. In removing Mugabe, they promised and offered people change.

They managed to temporarily persuade and gain the support of erstwhile detractors, such as the United Kingdom, and the sceptical support of many Zimbabweans. In two short years, they have squandered it all: the hope, the goodwill, the promise, the trust. They have also lost the trust of their own supporters and each other. They have run out of excuses.

The sanctions excuse, used effectively by Mugabe, has lost its shine: it no longer cuts it as Zimbabweans realise that ruling elites continue to plunder and live large while they suffer. But can Mnangagwa still salvage the situation or will it roll on towards a cliff edge?

The former looks unlikely, in the light of honest refection on the past two years, a realisation that there are simply no more cards for him or Zanu PF to play, when it comes to fudging the economy and politics, and also that relying on coercion will soon stop working. The hardline ruling party in Ethiopia, EPRDF, came to a similar conclusion after many years of relying on repression: it realised that there was a real chance of losing everything.

If Mnangagwa and his comrades reach this epiphany, they may yet survive and play a part in creating a different future. At almost 80 years old, having served for almost 60 years in government and having orchestrated and watched Mugabe being humiliated, it can be assumed that Mnangagwa would want a different fate.

This would ideally involve an inclusive negotiated process to address the country’s political, economic and social problems, preferably moderated by an external actor. Recently, South Africa has hinted that it is losing patience with the crisis, which may signal its willingness to mediate. If Mnangagwa and Zanu PF have no answers, neither it seems does the MDC, which has shown hesitation and ambiguity in its intentions.

While the deteriorating economic conditions provide the typical context for popular uprisings of the kind seen in which ruling parties were ousted in Egypt, Tunisia and more recently Bolivia, Algeria and Sudan, this is unlikely to happen on its own. Besides, it is hardly a viable strategy.

The MDC will have to be more deliberate and intentional. Doing nothing is as bad as Mnangagwa waiting and hoping nothing will come of the decline. If a negotiated solution is preferred, the MDC will have to push for one.

If a popular uprising is desired, it will have to lead and direct it. A spontaneous, leaderless, uprising by frustrated and angry citizens is also likely. This was the case in Egypt and to a great extent Algeria and Sudan. This option is what both Mnangagwa and the MDC should be worried about, as it places both outside the game.

Revolving coup door?

In the meantime, it is an open secret that there are disagreements at the highest levels inside government and Zanu PF. It is conceivable that the prevailing situation is not the one envisaged by those soldiers drafted into the coup who are now worse off than during the Mugabe era.

There are reports that junior officers are suffering squalid and dehumanising living and working conditions. If the state of ordinary Zimbabweans is a measure, this is unsurprising. There is talk of another coup.

Experience from elsewhere shows that once it has been opened, the door leading to military overthrow of a government is hard to close. To that extent, whether it is another coup or increased citizens’ agitation, not just for change but for survival, Zimbabwe seems headed for a major confrontation.

Rather than wait for it to happen and try to pick up the scattered pieces afterwards, the Southern African Development Community, led by South Africa (which has much to lose), the African Union and international bodies need to refocus their spotlight on Zimbabwe once again. But this time, they must ensure that the political change will genuinely refect the will of the people and not the small and predatory elite that now fights over the country’s decaying carcass.

*About the writer: Siphosami Malunga is an international human rights lawyer and executive director of the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (Osisa).

1 Comment